Archival processing: n. ~ 1. The arrangement, description, and housing of archival materials for storage and use by researchers.

Processing the RCA Victor Company negatives has been a collaborative project that has taken over a year to complete. The collection contains approximately 124,000 negatives that were salvaged from destruction in 1993 by the RCA Company historian, Frederick O. Barnum III. What follows is a step-by-step overview of the labor involved in processing this large and complex collection.

Step One:

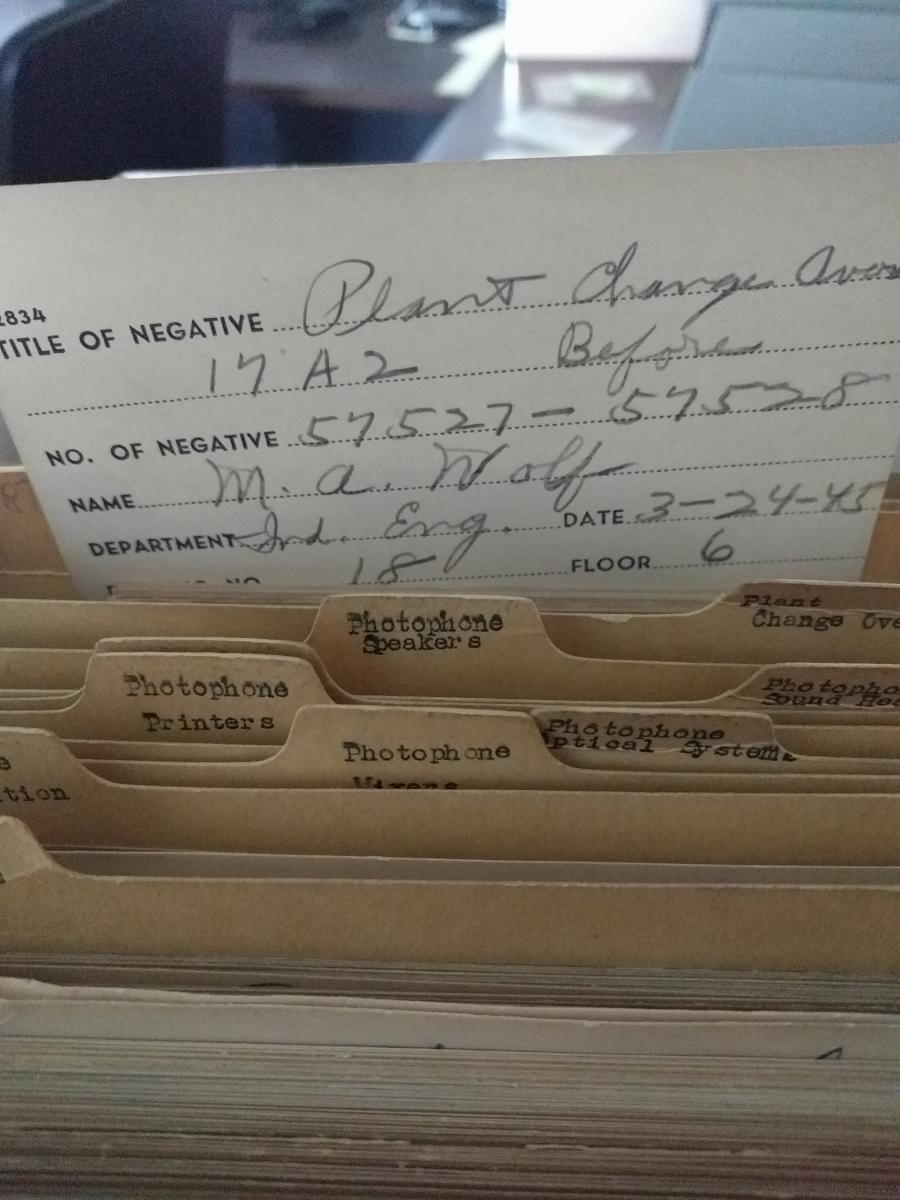

The collection came with a card index created by RCA staff that provided identification of the negatives. The negatives were assigned numbers which were recorded on the negative and on the index card, so that the identification could be matched with the image.

There were thousands of index cards, all handwritten in multiple (and not always entirely legible) handwritings. The Audiovisual Reference Archivist, Lynsey Sczechowicz led a team of volunteers to transcribe the index cards into an Excel spreadsheet. Thank you to our volunteers Marlene Knowles, Susan Cherrin, and Kathleen O’Hara for their work!

Step Two:

The RCA negatives needed archival enclosures for proper storage and preservation. Like most incoming collections, the negatives were stored in non-archival folders and boxes. About 10% of the negatives in the collection are severely damaged and will need to go through a conservation process called “stripping” which requires the use of solvents to remove the image layer of the negative from the damaged base to preserve the image. This is both time consuming and costly but necessary considering their condition.

We knew that the condition of each negative varied and that not all negatives required the same amount of care. We worked in consultation with the Library Conservator, Laura Wahl, to establish condition levels and decided to isolate the most damaged negatives from the rest of the collection. The most damaged negatives had significant creases and folds in the base layer caused by years of expansion and contraction during their time in poor storage conditions.

Two interns, Becky Koch and Melanie Grear went through each box of negatives and did the following:

- Ordered the negatives by the number assigned by RCA-Victor staff

- Matched the negative number range to the data entered by volunteers in an Excel spreadsheet

- Wrote the negative number and descriptive information on an archival folder

- Interleaved the negatives with acid-free archival paper

- Placed the group of negatives into the archival folder and then into an archival box

- Notated in our spreadsheet how many negatives were in each folder and noted if any were missing

- Notated the condition of the negatives and isolated those that required conservation

Koch and Grear repeated the above process for over 100,000 negatives. They discovered some negatives had been destroyed by RCA in 1980 which accounted for the information we transcribed from the index cards without a corresponding negative. On the other hand, there were many negatives that we did not have an index card which meant we had no information about them. For those negatives, staff created the identifying information.

Step 3:

Archivist Angela Schad and I created descriptions for over 30,000 unidentified negatives. Curator Kevin Martin worked on descriptions for the most severely damaged unidentified negatives.

Working with negatives is more challenging than photographs since the image is reversed and needs light behind it to see the image. We identified the negatives, updated the spreadsheet and completed the information on the archival folder.

We assigned subseries (categories) to each folder in the entire collection. We based these on the subjects assigned to each image in the RCA card index. We grouped and arranged the negatives into subjects and categories to enhance the access for our researchers.

Step 4:

When each folder was assigned a series (subject) and a subseries (category) in the spreadsheet, it was time to make the physical collection match the order of spreadsheet. Each folder was placed in the correct order and boxed accordingly. We wrote the location information on each folder and added it to the Excel spreadsheet. Then labels were made for every box. The collection contained 298 boxes with a final count of approximately 124,000 images.

Step 5:

There is a specific programming language used for archival finding aids called Encoded Archival Description (EAD). In this step, data is manipulated in the Excel spreadsheet to conform to a template that can be converted into EAD. Once converted, the EAD is imported into our archival collection management system so it can be formatted for a finding aid for online access along with the rest of our online collection data.

In addition to the negatives, there is a smaller set of photographs and 16mm films in the collection. A listing of all the content can be seen in the finding aid that is now available in our online database here.

NEXT STEPS:

The collection is now open to the public and material can be requested using the data in the online finding aid. There are still a few thousand negatives so damaged that we cannot make them accessible for research. The hope is to raise money through grant funding to support their conservation.

Our department plans to digitize a selection of negatives by the end of the year. These will be posted to our digital archive for online access.

I have processed thousands of linear feet of archival materials and hundreds of collections. I have processed much larger collections than this one, however, I have never had a collection as labor intensive or as collaborative among so many people as the RCA Victor Company negatives.

Thank you to Fred Barnum for saving this important collection from the trash heap so that it is now available to researchers.

Laurie Sather is the Audiovisual Archivist at Hagley Museum and Library.