Paper is the flesh of the archive. It can be so familiar that the sensitive researcher can sometimes date a collection by smell and feel. Light must and cardboard—within the last fifty years. Damp, heady, sharp, nearly chemical fumes—we’re in much older territory.

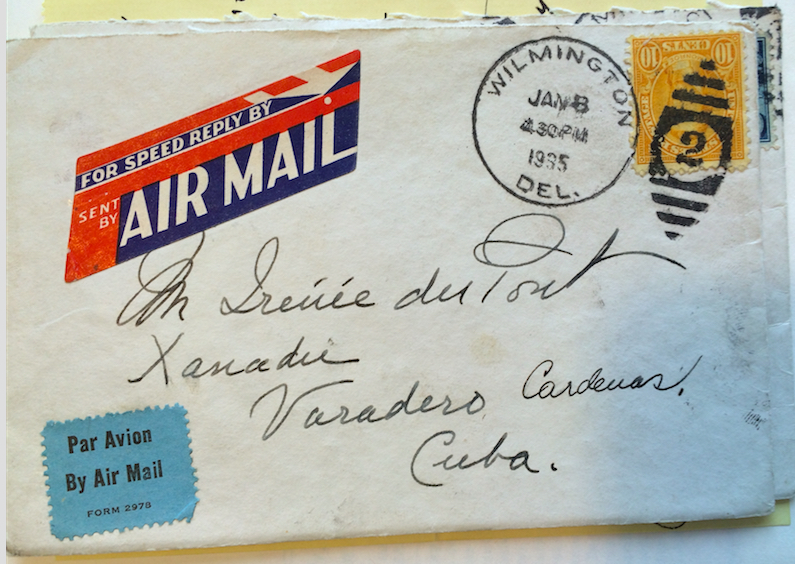

Variations in paper quality, size, shape, and color can also evoke a time and place. Hunter green lettering over mache paper stock, stark black serifs on eggshell, like this letter addressed with a single word, harnessing an incantatory power that carries them from the Brandywine Valley to the northern coast of Cuba with just a home "Xanadu" to guide them.

Paper is the historian’s constant companion, but it is rarely a substantive concern in itself. However, in my research on corporate philanthropy, the paper industry came to provide an interesting coda to my work.

Over the last year, my research at Hagley has focused mainly on the life and works of J. Howard Pew, the head of Sun Oil throughout much of the twentieth century and the main architect of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

During his lifetime, Pew tried to cordon off business from benevolence and religious projects from newly secular philanthropy. After his death, a large multinational paper company revealed how difficult it was to maintain these distinctions in practice.

In 1971, the year Pew died, the International Paper Company made a bid to purchase the General Crude Company of Houston, one of the spinoffs of Pew’s Sun Oil empire that was, through ownership of equities, partially controlled by the Pew Memorial Foundation. International Paper owned enormous swaths of land from which it harvested lumber, and it believed that an oil company would double the profits from that land, allowing it to harvest resources both above and below the ground.

When Dow Chemical got wind of this merger, a bidding war and drawn out legal battle over who had the right to control the fate of General Crude erupted. Ultimately, the Pews decided to accept the International Paper deal over the objections of both Dow and General Crude.

This incident reveals how difficult it is to maintain a bright line between the business world and a disinterested non-profit sector. What the Pews and other families at the helms of large and complex endowments teach us—and what my own research focuses on more broadly—is that the vehicles through which power is exercised and the terms in which it is understood are always shifting.

I believe that our contemporary studies of the corporation and of business history would be enriched by less attention to labels like "for-profit", "non-profit", and "governmental" and "non-governmental agencies," and a keener focus on the different types of relationships these organizations can foster to capital, to different types of people, and to economic and religious logics.

In making sense of the corporate archive we must have our eyes trained sharply on both material influence and culture formation, on contemporary understandings of virtue and vice, and on the draw of both power and paper.

Andrew Jungclaus is a doctoral student in the Department of Religion at Columbia University. His research focuses on the evolution of philanthropic models within the history of capitalism.