Regina Lee Blaszczyk writes about her new book, The Color Revolution, published by the MIT Press in Sept. 2012. The book was recently praised by the New York Times and International Herald Tribune for its exploration of the “scientific ingenuity, entrepreneurial verve, and seductive colors” in modern America.

Origins

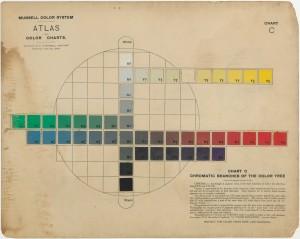

As a studio major in college, I produced artwork that involved the use of bright, contrasting colors. My senior project involved a show of my work, plus a 100-page thesis that in part focused on the history of design and culture. My fascination with color grew as I studied the designs of William de Morgan and William Morris and the modernist paintings of Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. For my color seminar, we read the Interaction of Color by Josef Albers and learned about Chevreul’s theories of color psychology. I did my homework assignments using expensive color papers marketed under the trade name Munsell.

Years later, as a Smithsonian curator, I was prowling around old journals at the Library of Congress, and in the first issue of Fortune, I ran across an article called “Color in Industry.” The article focused on the colorful consumer goods that hit the American market during the 1920s, and gave a fancy name to the phenomenon: “the color revolution.” Maybe it was my college training in color theory, but the Fortune article and the idea of a “color revolution” stuck.

Finding Sources

Further down the road, I finished my PhD in the Hagley Program at the University of Delaware and was settling into a new job in Boston when the light bulb went off. I began to ask, “What was revolutionary about the color revolution?” Had the color explosion of the 1920s only been a fad, or did it represent something significant? Could color help us understand relationships among business, innovation, and consumer culture? And more important, what kinds of sources were available to answer these questions?

I began my hunt in the Back Bay of Boston, where Albert H. Munsell—the entrepreneur who founded the Munsell Color Company, a firm whose successors still make color supplies for educators—spent his career as a drawing professor at the Massachusetts College of Art. Mass Art hadn’t kept many of his papers, but the librarian dropped vague hints about a “Munsell color diary” owned by “a museum in New York.” I knew that my study of the color revolution would have to include discussion of America’s most famous color educator, so I looked south.

I began my hunt in the Back Bay of Boston, where Albert H. Munsell—the entrepreneur who founded the Munsell Color Company, a firm whose successors still make color supplies for educators—spent his career as a drawing professor at the Massachusetts College of Art. Mass Art hadn’t kept many of his papers, but the librarian dropped vague hints about a “Munsell color diary” owned by “a museum in New York.” I knew that my study of the color revolution would have to include discussion of America’s most famous color educator, so I looked south.

A few calls and emails later, I found a treasure trove of archival materials—and laid the foundation for the book that would be called The Color Revolution. The mystery museum in New York was the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum, which had a massive color collection stored in a remote warehouse. This collection had been assembled by color practitioners from the Inter-Society Color Council. It included early ISCC newsletters, a transcript of Albert Munsell’s “color diary,” and early documents from an important, but unrelated, organization, the Textile Color Card Association of the United States. I immediately put Michael Nash, the archivist at Hagley, in touch with Stephen Van Dyk, the librarian at the Cooper-Hewitt. Eventually, the Cooper-Hewitt transferred the collection to Hagley, where it now part of one of the world’s best historical archives on color.

Color and the Creative Industries

The vast color collections at Hagley are not the only archives I used in The Color Revolution—I prowled around libraries in Paris and London and in Detroit and Washington—but they were among the most important. Many books on color are written from a visual culture perspective, examining the colors themselves as evidence of cultural change. Another thread of research focuses on the scientific and technological history of dyes, paints, and pigments, including the synthetic organic chemical industry. Art historians have examined the role of color theory in the evolution of artistic styles.

The vast color collections at Hagley are not the only archives I used in The Color Revolution—I prowled around libraries in Paris and London and in Detroit and Washington—but they were among the most important. Many books on color are written from a visual culture perspective, examining the colors themselves as evidence of cultural change. Another thread of research focuses on the scientific and technological history of dyes, paints, and pigments, including the synthetic organic chemical industry. Art historians have examined the role of color theory in the evolution of artistic styles.

My work is influenced by this scholarship, but it addresses an entirely different set of questions. My work focuses on the history of design and innovation for the consumer culture. I am concerned to understand the nature of invention and innovation, and to explore how creative people initiate change within institutions and the broader culture. In part, these are the questions of the new business history, which is concerned to connect enterprise and society. But they are also uniquely informed by my longstanding interest in the history of design and the creative industries.

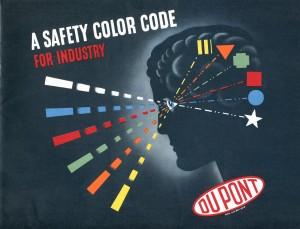

Good documentary evidence is needed to get to the heart of the creative process. The color archives at Hagley are just that: they are mostly business records of individuals, firms, and trade associations, including internal reports, committee memos, and correspondence. These collections opened the doors on to the world of America’s color pioneers, allowing me to see how and why they invented design tools like color standards and color forecasts. Thanks to these collections, The Color Revolution tells a whole new story about the creative professionals who called themselves “color forecasters,” “color stylists,” and “color engineers.”

Treasures

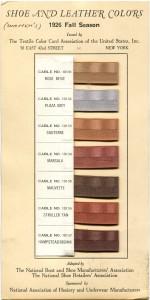

The Hagley collections are essential for anyone who wants to study the history of commercial color practice from the late-1800s to the mid 1900s. By way of example, the ISCC collection is a treasure trove of 19th-century French color cards. These are foldout books lined with silk ribbons, showing predictions of the fashion colors for the new season. The French textile industry reportedly introduced these color cards in the 1870s. They were mostly used to market dyeing service to local fabric mills, but they were also exported to the United States where textile designers, milliners, and retail buyers adopted them as design and merchandising tools. Many American museums have German dye handbooks, but French color cards are harder to find, at least in the United States.

For The Color Revolution, the most important holdings at Hagley were the institutional archives of the Textile Color Card Association, which was the first American organization dedicated to color standardization and color forecasting. The TCCA papers show how the American textile and fashion industries sought to break away from the color dictators of Paris during World War I and how they adapted Paris colors to the American scene in the interwar years. The leading light in this effort was Mrs. Margaret Hayden Rorke, who managed the TCCA from 1919 through 1954. I was able to follow the career of Mrs. Rorke, and to show exactly how she obtained information from Paris colors and adapted French hues to American tastes. The archives contain the letters and cables from her agents in Paris; these “Paris reports” describe the color choices of all the couture houses, the shoemakers, glovers, and boutiques. It is rare to find materials that allow the historian to trace the flow of fashion information from Paris to New York.

For The Color Revolution, the most important holdings at Hagley were the institutional archives of the Textile Color Card Association, which was the first American organization dedicated to color standardization and color forecasting. The TCCA papers show how the American textile and fashion industries sought to break away from the color dictators of Paris during World War I and how they adapted Paris colors to the American scene in the interwar years. The leading light in this effort was Mrs. Margaret Hayden Rorke, who managed the TCCA from 1919 through 1954. I was able to follow the career of Mrs. Rorke, and to show exactly how she obtained information from Paris colors and adapted French hues to American tastes. The archives contain the letters and cables from her agents in Paris; these “Paris reports” describe the color choices of all the couture houses, the shoemakers, glovers, and boutiques. It is rare to find materials that allow the historian to trace the flow of fashion information from Paris to New York.