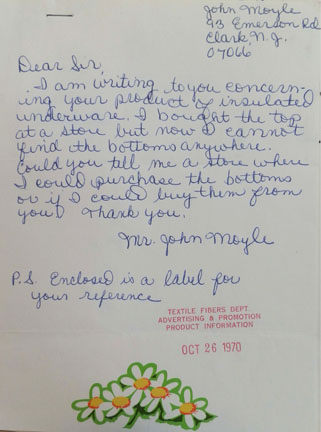

With polar vortexes hitting U.S. cities hard this winter, many Americans are surely turning to the long underwear in their closets with some frequency. What do you do, though, if you have a great long underwear top that keeps you warm and dry, but not the bottoms to match? In 1970, John Moyle’s logical response was to look at his shirt tag and write to DuPont for information. Where, Moyle wanted to know, could he buy Dacron 88 Fiberfill? He liked how his shirt “provides comfortable warmth for persons engaged in work or sport in winter weather.”

The catch? DuPont didn’t actually make insulated underwear. As Adaline Ryan, of Product Information, responded to the confused New Jerseyan: “the Textile Fibers Department manufactures the basic filling material only – Dacron® polyester fiberfill. We do not construct insulated garments of any kind. As a result, we are not in a position to forward a garment to you.”

Moyle’s confusion was understandable. In the second half of the twentieth century, as DuPont’s Textile Fibers Department sought applications for their new synthetic fabrics, they often looked to the outdoor industry. Clothing companies that sold gear to hikers, campers, and climbers were interested in the qualities of synthetics such as Dacron and Polypropylene. DuPont helped stimulate this interest by advertising their materials directly in outdoor lifestyle magazines like Field and Stream and Backpacker. These advertisements sold the concept of synthetic materials, but not an actual product. Consumers like Moyle could leaf through a Field and Stream catalog and learn about Dacron—“It’s warm, It’s light, It’s comfortable, It’s quick drying.” It was then up to the consumer to go looking in a brick and mortar store like Recreational Equipment, Incorporated (REI) or a catalog like Duxbak’s for the latest in outdoor synthetic materials.

Moyle’s letter was not the first time DuPont’s Product Information representative received a request for clothing. This was good news for DuPont, as subsequent market research reports confirmed—registered trademarks had brand recognition. Moyle looked for Dacron Fiberfill insulated products as a result of careful, directed advertising meant to raise the profile of DuPont innovations. Indeed, Moyle’s instinct to write to the chemical giant rather than Duxbak, the actually producer of his shirt, shows the success of DuPont’s branding efforts.

Just like John Moyle, I got a lesson in how DuPont ran its business during my dissertation research at the Hagley Museum and Library. Catalogs and magazines since the 1970s have runs ads from Du Pont, 3M, and other companies pushing their high-tech innovations. It was only when I came to the Hagley and examined the DuPont textile fibers collection that I understood why those advertisement existed, and how they operated for consumers like John Moyle.

Rachel Gross is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she is completing her dissertation “From Buckskin to Gore-Tex: Consumption as a Path to Mastery in Twentieth Century American Wilderness Recreation.”