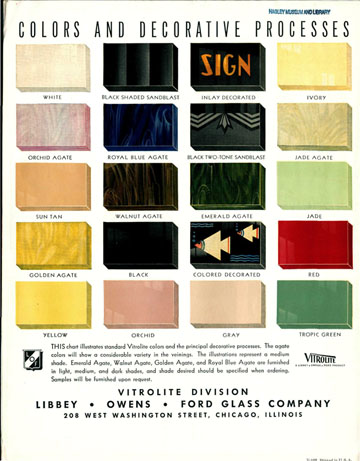

Last week a Hagley library patron was conducting research on food safety. Among the items she requested was a trade catalog called “Vitrolite Sanitary Tables and Counters,” published in 1922. The cover features an illustration of two elegantly dressed women sitting at a table looking at menus, waiting to order their lunch. I wondered what made their table “sanitary,” and I wondered what Vitrolite was. To satisfy my curiosity, I knew I would have to look a little more closely at this catalog, and dig a little deeper into our collection. I know that in the past wood, marble and tile were used for countertops, then later formica, and granite, and even DuPont ‘s Corian were popular, but I never heard of Vitrolite. Was that the material of choice in the 1920s? The catalog said that “the sparking clean whiteness of Vitrolite counters and table tops is a standing invitation to tarry. Its delightfully cool, bright surface is just the place to serve palatable drinks and dainties. It keeps clean— nothing stains it and it just wears and wears…” I learned that Vitrolite was an opaque structural glass product. In 1900, the Marietta Manufacturing Company claimed to be the first producer of pigmented structural glass, rolling the first sheet of a substitute for marble, Sani Onyx. The company advertised Sani Onyx as an easy-to-clean, germ-free surface. Penn-American Plate Glass Company quickly joined its ranks, manufacturing white and black Carrara Glass around 1906. Then the vitreous marble product called Vitrolite was produced by The Vitrolite Company from 1908-1935, and then by Libbey-Owens-Ford from 1935-1947. Since vitreous marble is glass, it’s a non-porous substance that does not harbor bacteria, so it was used extensively in bathrooms and kitchens as a substitute for marble counter tops, table tops, and restroom partitions. The downside of this product, is that it is very fragile, so it can break easily. Vitreous marble became obsolete with the emergence of cheaper and more durable substances, and has not been manufactured in the United States since 1947. While the first catalog I examined claimed that the Vitrolite was white, later catalogs show the product was produced in many colors, and that it was used not only as a product for indoor use, but one with architectural uses on the exterior of buildings!

Last week a Hagley library patron was conducting research on food safety. Among the items she requested was a trade catalog called “Vitrolite Sanitary Tables and Counters,” published in 1922. The cover features an illustration of two elegantly dressed women sitting at a table looking at menus, waiting to order their lunch. I wondered what made their table “sanitary,” and I wondered what Vitrolite was. To satisfy my curiosity, I knew I would have to look a little more closely at this catalog, and dig a little deeper into our collection. I know that in the past wood, marble and tile were used for countertops, then later formica, and granite, and even DuPont ‘s Corian were popular, but I never heard of Vitrolite. Was that the material of choice in the 1920s? The catalog said that “the sparking clean whiteness of Vitrolite counters and table tops is a standing invitation to tarry. Its delightfully cool, bright surface is just the place to serve palatable drinks and dainties. It keeps clean— nothing stains it and it just wears and wears…” I learned that Vitrolite was an opaque structural glass product. In 1900, the Marietta Manufacturing Company claimed to be the first producer of pigmented structural glass, rolling the first sheet of a substitute for marble, Sani Onyx. The company advertised Sani Onyx as an easy-to-clean, germ-free surface. Penn-American Plate Glass Company quickly joined its ranks, manufacturing white and black Carrara Glass around 1906. Then the vitreous marble product called Vitrolite was produced by The Vitrolite Company from 1908-1935, and then by Libbey-Owens-Ford from 1935-1947. Since vitreous marble is glass, it’s a non-porous substance that does not harbor bacteria, so it was used extensively in bathrooms and kitchens as a substitute for marble counter tops, table tops, and restroom partitions. The downside of this product, is that it is very fragile, so it can break easily. Vitreous marble became obsolete with the emergence of cheaper and more durable substances, and has not been manufactured in the United States since 1947. While the first catalog I examined claimed that the Vitrolite was white, later catalogs show the product was produced in many colors, and that it was used not only as a product for indoor use, but one with architectural uses on the exterior of buildings!

Vitrolite, when used for internal and external tiling and façades of buildings is often associated with the streamlining of the Art Deco and Art Moderne movements of the 20's and 30's that epitomized the ultramodern look. Architect Cass Gilbert adopted it in the interior design of the Woolworth Building (1912-1913) in New York City. Its polished, slick and shiny surface could be curved, textured, sculptured, cut, laminated, colored and illuminated. Vitrolite could also be readily retrofitted to existing buildings as part of efforts to "Modernize Main Street" in the Great Depression era. A catalog titled “Vitrolite in architecture and decoration,” published by the Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company, c1937 lists the many uses for Vitrolite: Store fronts, lobbies of hotels and office buildings, for walls, ceilings and wainscoting of laboratories, bakeries, dairies. In hospitals, barber shops, meat markets. For lunch counters, bars, soda fountains, table tops, restaurants, confectionaries and taverns. We have two Vitrolite catalogs from the 1930s, one for bathrooms and kitchens, and one for store fronts, and they both feature the same product color chart, showing that this versatile product was being marketed for two very different uses!

View Vitrolite Trade Catalogs in the Hagley Digital Archives:

Vitrolite Sanitary Tables and Counters

Vitrolite: Better than Marble as Applied to Homes and Apartment Buildings

Linda Gross is the Reference Librarian in the Imprints Department at Hagley Library.