I received an interesting reference question a few months ago from researchers trying to identify a vintage floral linoleum pattern that was used in a work of art created in the 1960s. They asked if we could find the pattern in some of the linoleum trade catalogs in our library collection.

The researchers had searched Hagley’s online library catalog and identified a range of catalogs dating from 1924 to 1952.

I love old linoleum patterns, having lived in a few old houses where the tastes of many generations of inhabitants could be documented through the layers of the kitchen floor, so I looked forward to this challenge!

I pulled the catalogs in question, and examined them one by one for any matching patterns. Unfortunately I wasn’t able to find the pattern in question, but I fell in love with the quirky designs from each decade all over again.

Linoleum is a term used for a smooth floor covering made from a solidified mixture of linseed oil, flax, cork, wood flour and pigments, pressed between heavy rollers onto a canvas backing.

Linoleum was created by an Englishman named Frederick Walton. The story goes that one night in 1855, he forgot to seal a container of linseed oil that he was using as paint thinner, and a skin of solidified oil formed on top of the oil. He peeled it off and began to think of ways that this rubbery substance might be used. Walton experimented with ways to speed up the lengthy process of creating a solid product.

In 1860 Walton applied for the first of a series of patents, and named this new material ‘Linoleum,’ from the Latin words linum (Latin for flax) and oleum (Latin for oil). Walton established the Linoleum Manufacturing Company Ltd., in 1864, in Staines, England. By 1869, Walton’s Linoleum had become so popular that he was exporting to the rest of Europe and the United States.

The chief competition to Linoleum was oil-cloth, which had been an economical and practical floor covering since the 18th century. Linoleum was a superior product because it was thicker, more waterproof and longer-wearing.

Walton faced competition in the United States when Sir Michael Nairn, an established oil cloth manufacturer in Scotland, opened the American Nairn Linoleum Company in 1887 in Kearny, New Jersey. Nairn manufactured and sold his own brand of linoleum. Walton decided to sue Nair for trademark infringement for the use of the word that Walton had invented.

In 1878, the British Courts ruled against Walton, partly because he had failed to register linoleum as a trade name, but also because linoleum had become so commonplace, they determined that linoleum was a generic term.

Only fourteen years after linoleum was invented, it had become a ubiquitous feature in homes and commercial buildings. Linoleum is considered to be the first product name to become a generic term.

Another important company in the flooring market in the United States was the Armstrong Cork and Tile Company. Thomas Armstrong, the son of Scottish-Irish immigrants from Derry, started his company in 1860 as a two-man cork-cutting shop in Pittsburgh. The company grew to be the largest cork supplier in the world by the 1890s. Searching for new cork-based products, the company decided to add linoleum floor covering to its line and, in 1908, the first Armstrong linoleum was produced in a new plant in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Lancaster, Armstrong Cork Co., circa 1928.

In 1902, the United Roofing and Manufacturing Co. in Pennsylvania started producing “Congo” roofing, supposedly named for the fact that asphalt used in the roofing material came from the African Congo. The company entered into an agreement with the Barrett Manufacturing Co. to have the Barrett plant in Erie, Pennsylvania manufacture Congo roofing. They soon realized that the three foot wide strips of Congo roofing material could easily be used as floor runners to deaden noise and minimize dust and dirt collection. To differentiate between the Congo roofing and the flooring material, the flooring was given the name Congoleum.

In 1924, the Congoleum Corporation acquired Nairn Linoleum Manufacturing Corporation and changed the name to Congoleum-Nairn, Inc. Together the company produced Congoleum felt-based flooring and Nairn linoleum.

Linoleum had many features that made it a popular choice for a floor covering. It provided a cushioned, comfortable floor, it was easy to clean, and it was durable. Linoleum was produced in an array of colors and patterns, including mosaics, tiles, marbles, and carpet patterns.

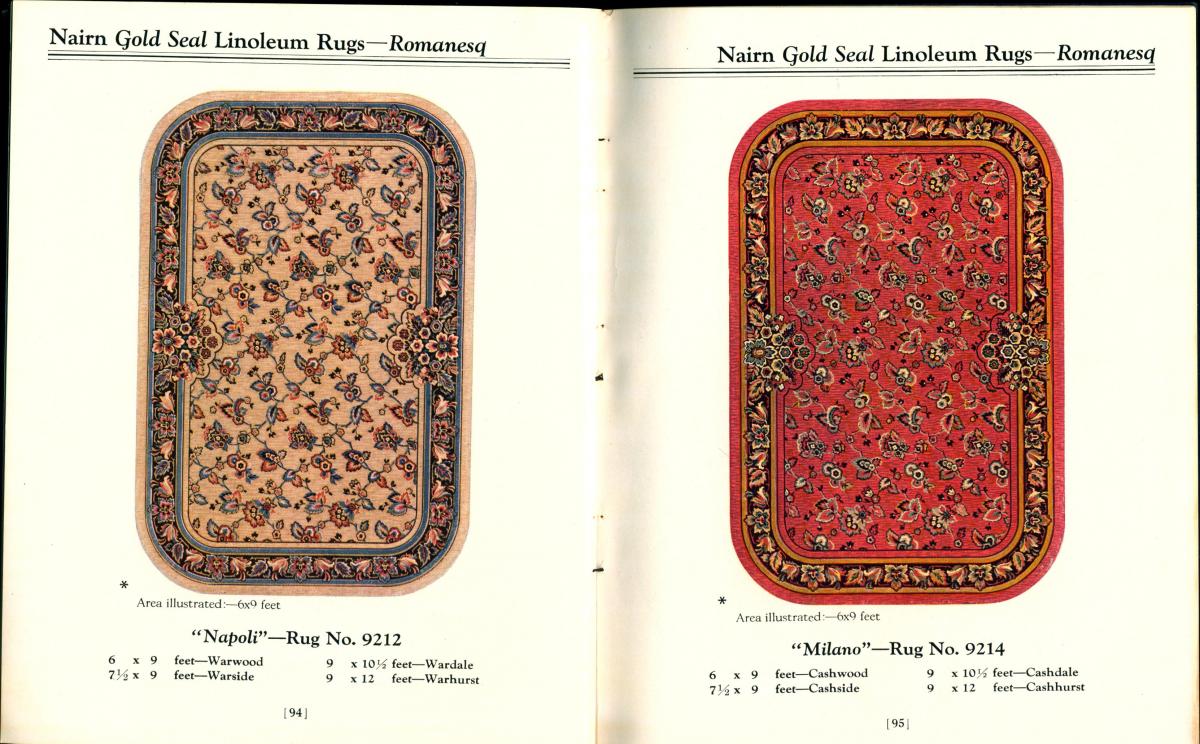

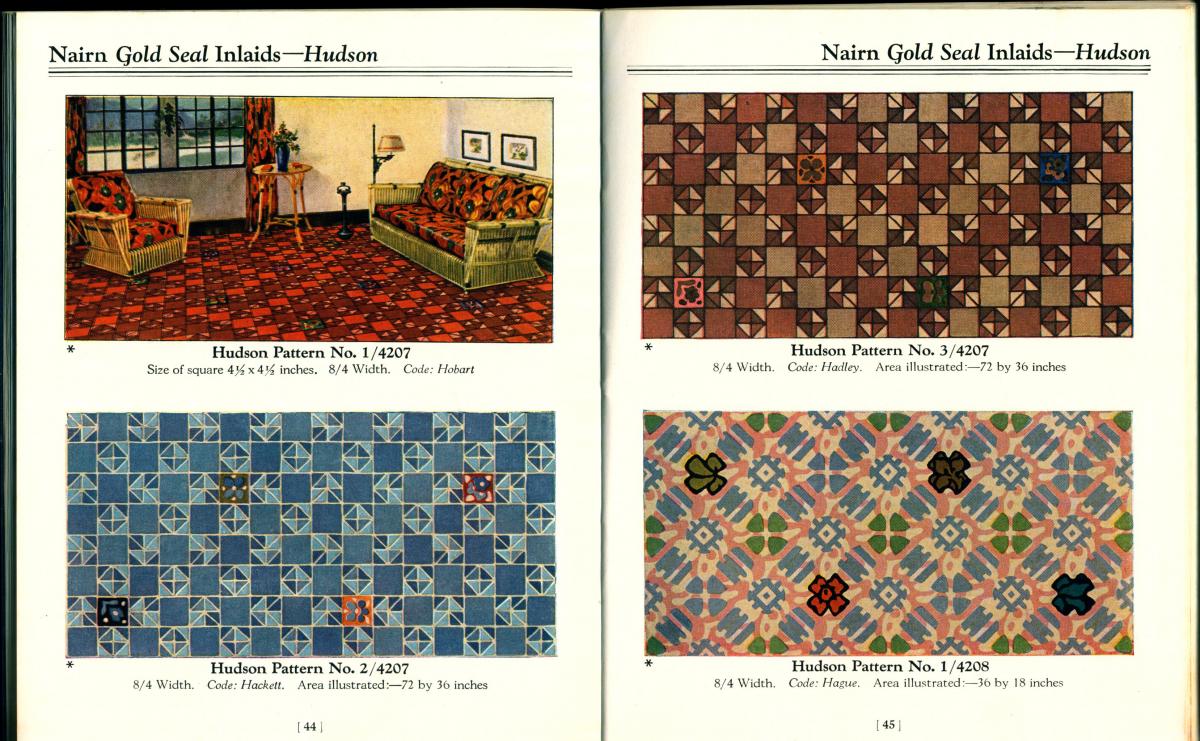

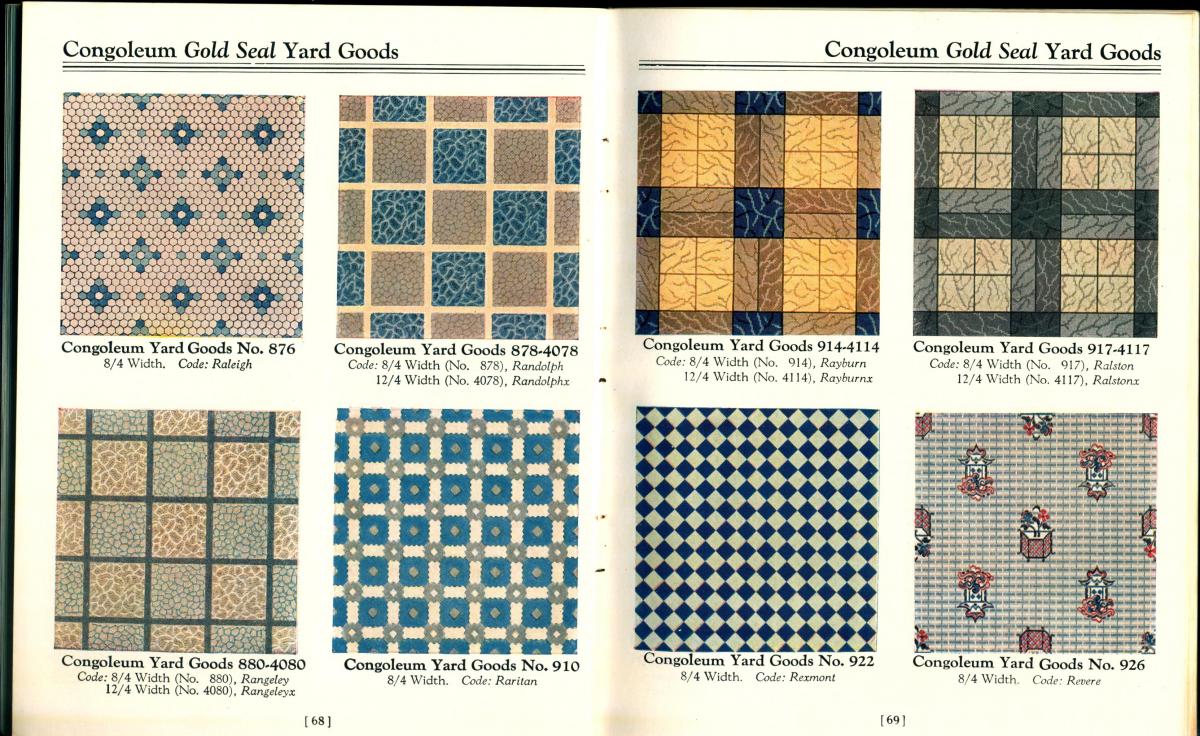

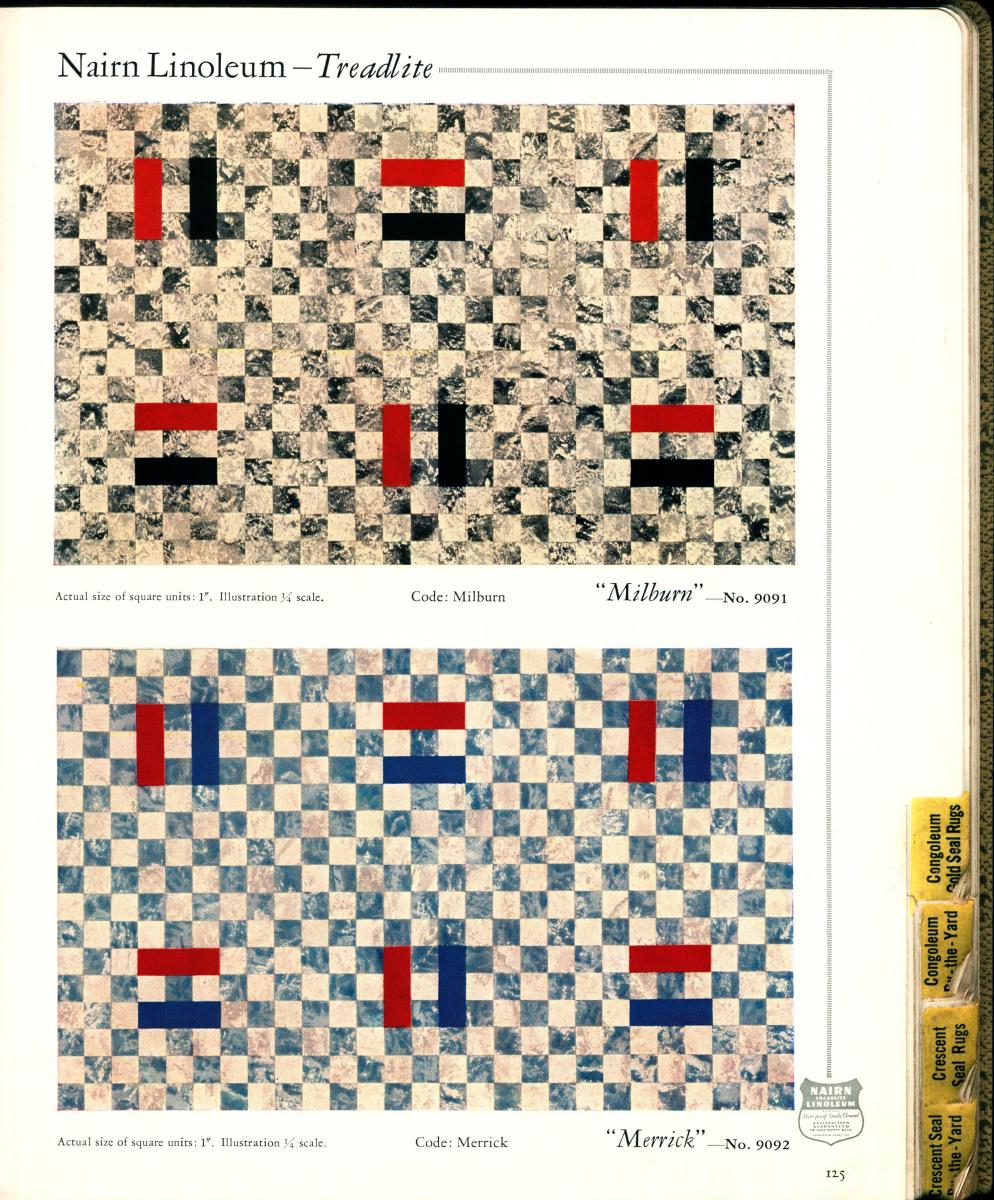

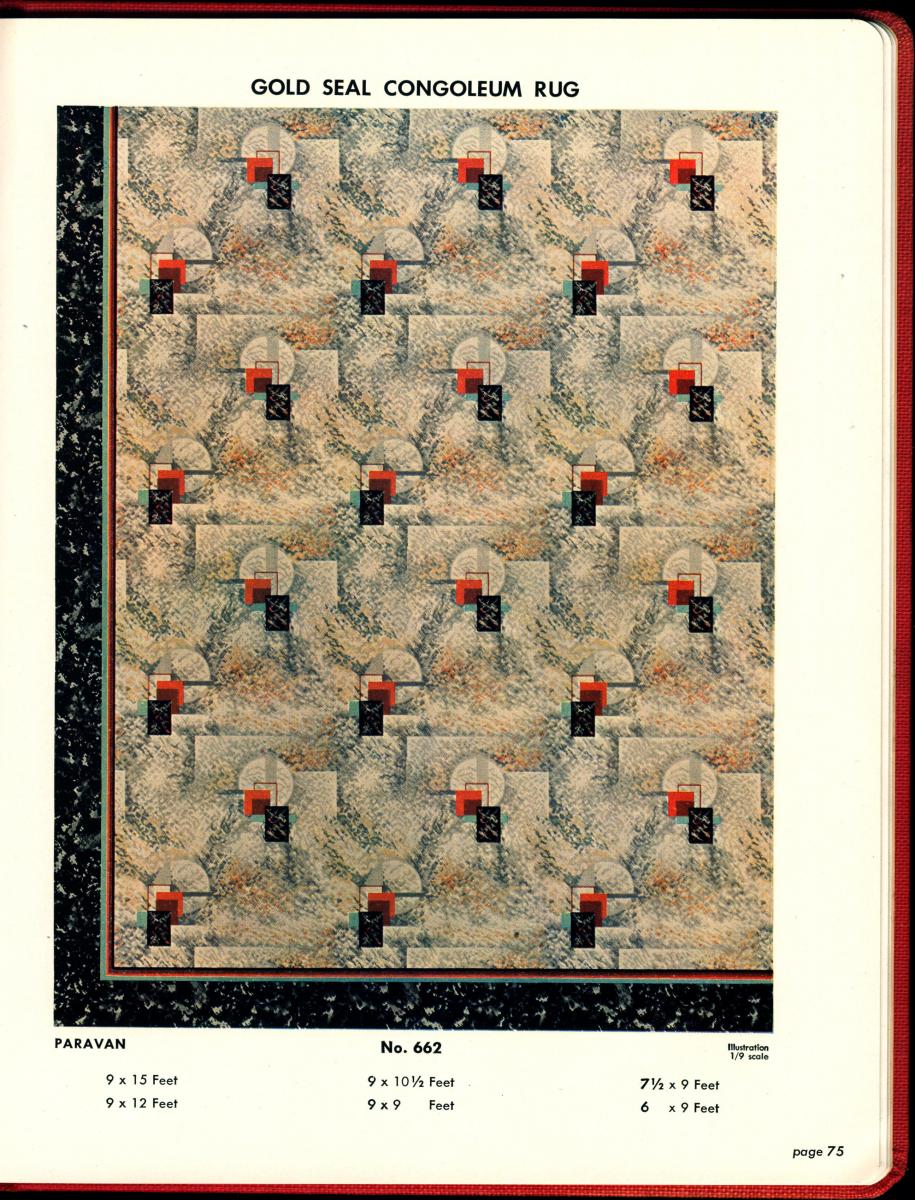

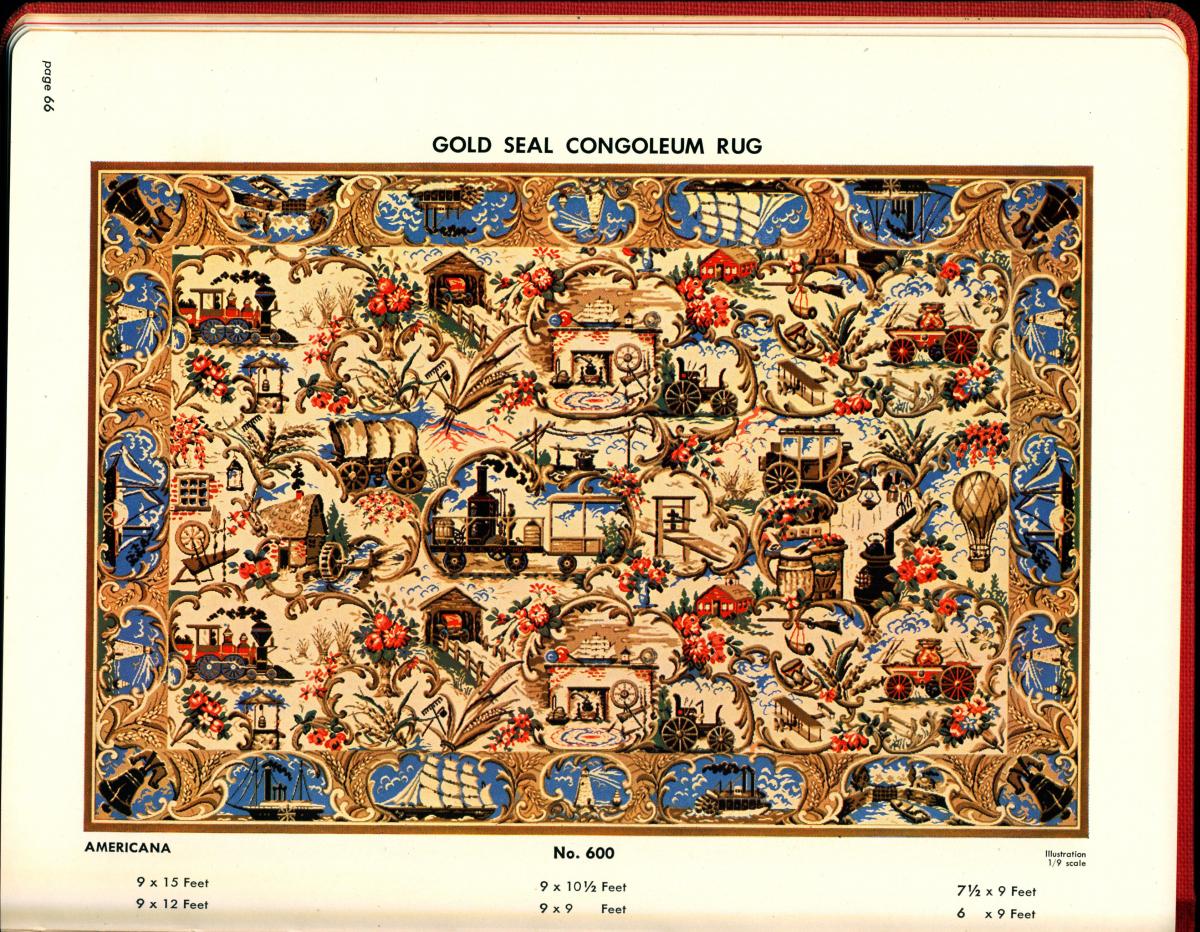

Here are some examples from some several years of the Congoleum-Nairn pattern book. First, from 1928:

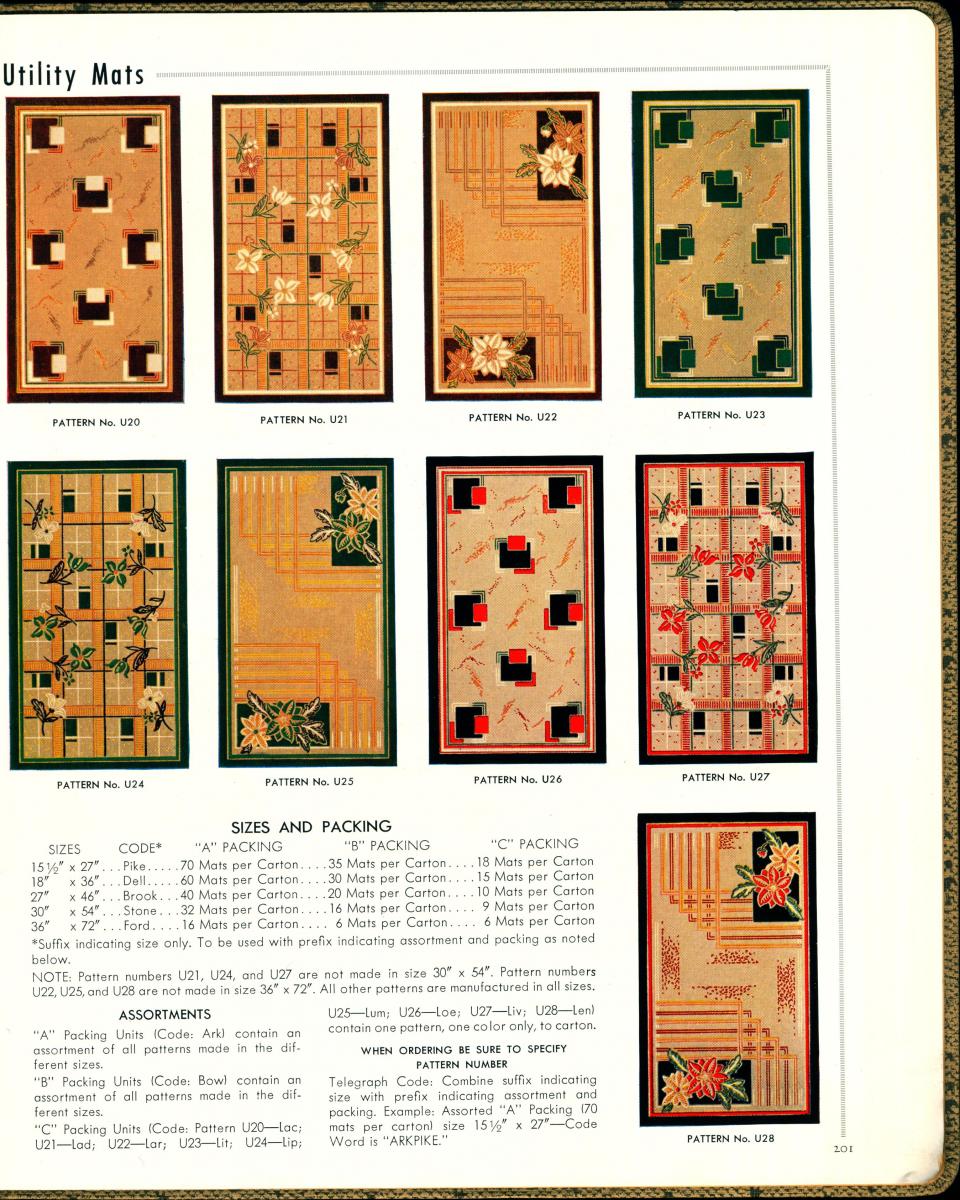

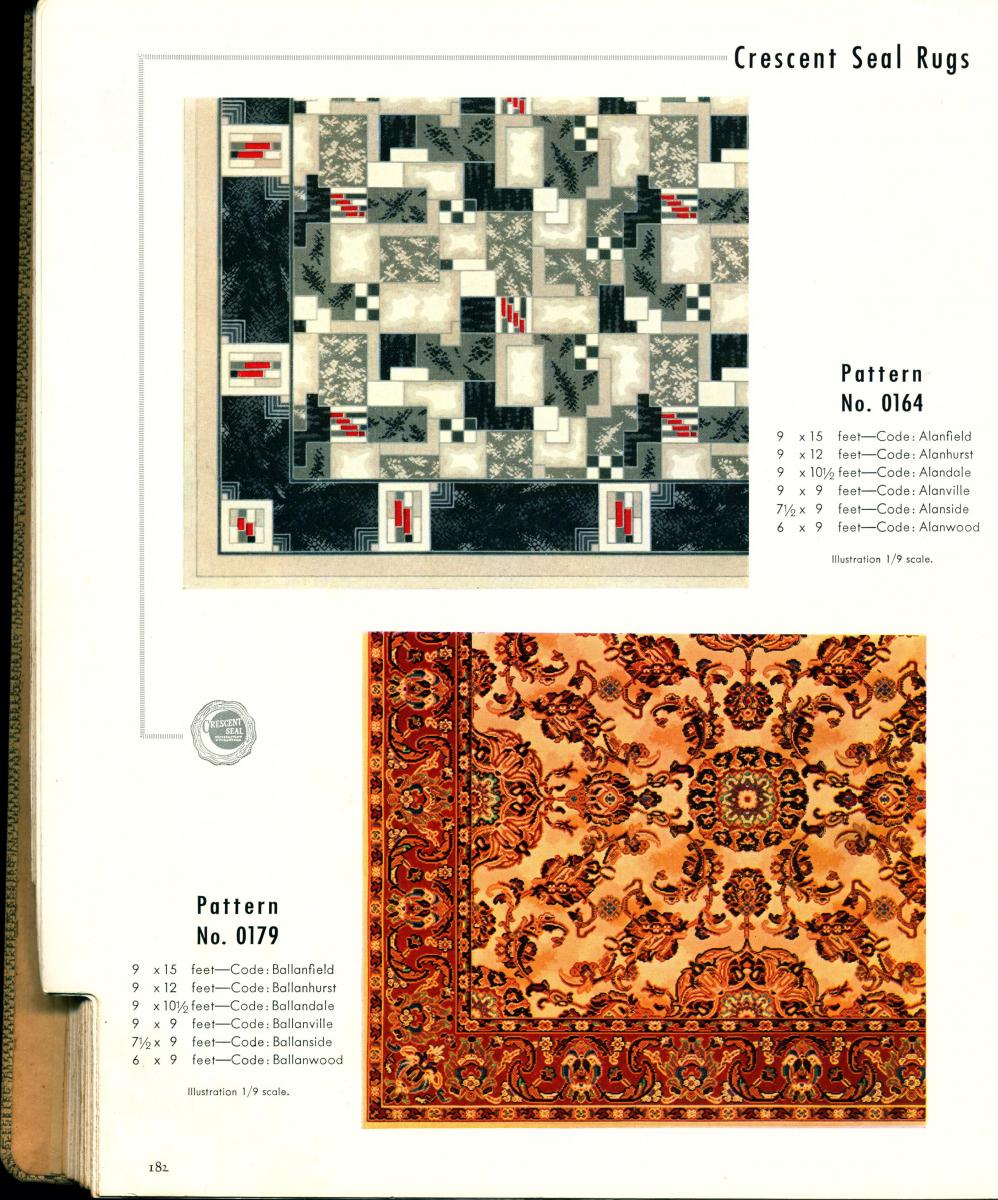

And some examples from 1939:

And finally, from 1947:

Linoleum was eventually replaced in the 1950s and 1960s with plastic-based products. Today, what people may refer to as linoleum is actually made from polyvinyl chloride, which has similar flexibility and durability to linoleum, but is relatively less flammable, and can be produced with greater brightness.

While linoleum is used less commonly today, high-quality linoleum is still available! It is used in many places, like hospitals and healthcare facilities because it is made of organic materials, is antibacterial, and non-allergenic. In fact, in 1997, vinyl-flooring giant Armstrong bought the world's second-largest linoleum maker, DLW (Deutsche Linoleum Werke,) reentering a market it had left in the 1970s.

A 2001 trade catalog from Forbo Flooring systems states that Forbo is the “world leader in linoleum." The Forbo Group is headquartered in Baar, Switzerland, but Forbo Flooring’s North American headquarters is in Hazelton, Pennsylvania.

Forbo's main brand for its core Linoleum collections is called Marmoleum. The designs range from subtle marbled designs to modern concrete and intriguing striped patterns. The catalog says that “There are over 300 colors and 12 different design structures to choose from.”

With so many choices, and with its natural composition and durability, linoleum may be found under our feet for many years to come.

Linda Gross is the Reference Librarian at Hagley Museum and Library.