The world of leisure activities (and the industries that support them) entered a new era 63 years ago this April. Over the spring and winter of 1962, a small group of students and employees at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) had been looking for a way to demonstrate the abilities of a new PDP-1 minicomputer recently installed in the MIT Electrical Engineering Department. The end result was Spacewar!, a simple, two-person combat game in which each player piloted one of two spaceships around a star. Spacewar! was not the first video game; computer scientists and physicists had begun developing rudimentary games on oscilloscopes, cathode-ray tube devices, and early computers since at least 1947. But what made Spacewar! unique was what happened next: it was shared.

Unlike other games, which were designed for use on a single machine or for demonstration purposes only, Spacewar! moved from one computer to another. First moving to other PDP-1 minicomputers in the university, then to computers used by students and employees at other universities in the area, the game became popular throughout the small computer programming community of the 1960s. It was available to anyone with access to the game's code, which was shared freely.

The free game would spawn what is now a $200 billion gaming industry; the first coin-operated arcade consoles—1971’s Galaxy Game and Computer Space—were both modified versions of Spacewar! While the cost and capabilities of early computers had effectively stifled the commercial opportunities for games like Spacewar!, moving games to standalone consoles for arcade parlors created new means to capitalize on the technology.

These opportunities only expanded as home computers and consumer electronics using computing technology became more commercially available to the general public. In 1972, Magnavox released the Magnavox Odyssey, the first commercially available video game console for home use. It was followed shortly thereafter by Atari’s console for the game Pong.

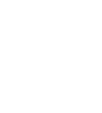

One early adopter included RCA (Radio Corporation of America) engineer Joseph Weisbecker, who had made a hobby out of building small home computers and encouraged the company to create small computers and consoles for consumers. In 1977, RCA released the STUDIO II video game console, built using a COSMAC 1802 CPU of Weisbecker’s own design.

STUDIO II was not a particularly successful product. The console was not competitive with other devices that went on the market around the same time, and RCA had decided to focus on educational games as a means of distinguishing itself in the field, which proved less popular than anticipated.

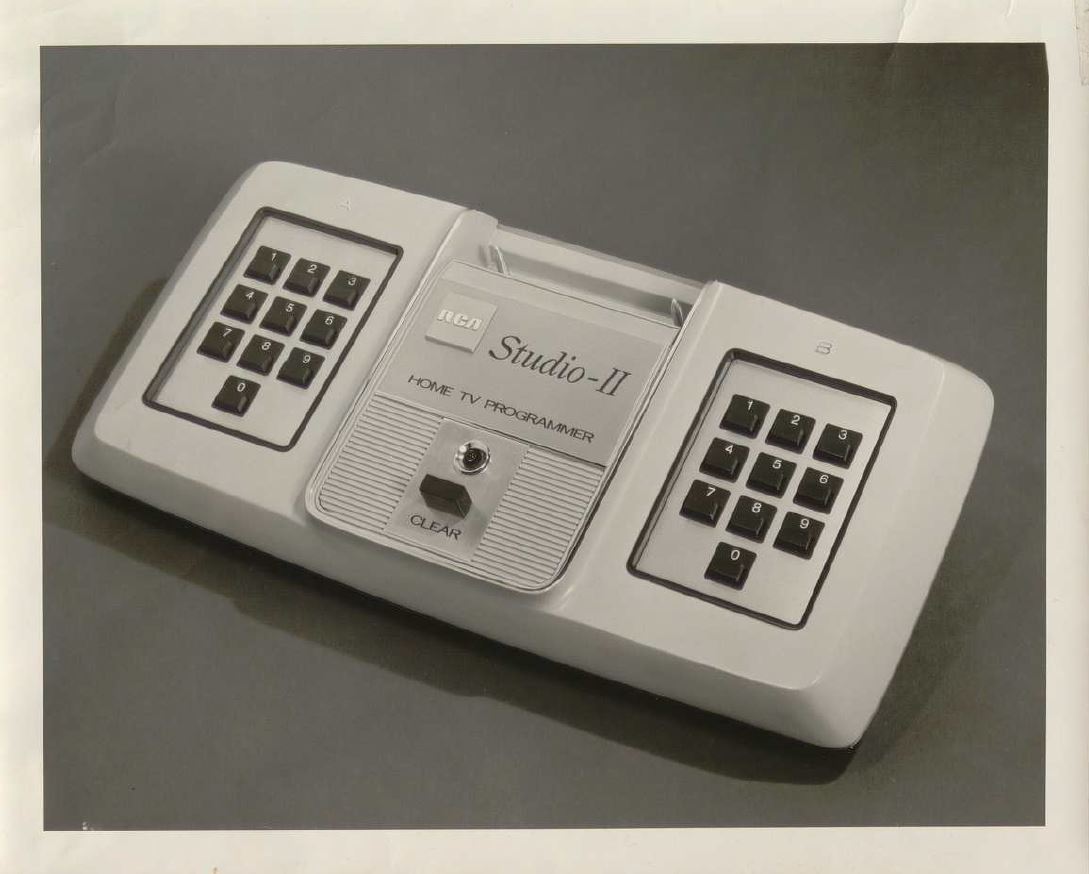

In addition to being an RCA employee, Joseph Weisbecker was also a computing enthusiast and entrepreneur. Through his home business, Komputer Pastimes, he authored a number of simple books and other works aimed at children and general audiences. His goal was to make computing technology understandable and accessible to a wider audience. Weisbecker was also the father of two daughters, Joyce and Jean (see right), who he also included in his work and hobbies, including in the creation of simple games for his homemade prototype FRED (“Flexible Recreational & Educational Device”) microcomputer.

Some of these games amounted to little more than programming instructions; projects like Snake Race and Jackpot would be published in RCA game programming manuals as type-in programs in for the RCA COSMAC VIP. They earned her a credit in the publication, but little else.

But in August 1976, Joyce Weisbecker’s TV Schoolhouse I for the STUDIO II sold to RCA for $250. With that payment, a teenage Joyce Weisbecker became both the world’s first professional female video game developer and the the first indie game developer. That sale was followed by the combination cartridge games Speedway/Tag, also for the STUDIO II system. Joyce also created games for the COSMAC VIP; selling Slide, Sum Fun, and Sequence Shoot in 1977.

Joyce’s time in the video game industry was, like the STUDIO II, short-lived. She began school at Rider University in the fall, and graduated in 1980 with a double major in computer engineering and actuarial science. Following a career as an actuary, in 1998 she resumed her education and earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a masters in computer science, and began work as a radar signal processing engineer designing digital filters.

Evidence of the Weisbecker’s contributions to the world of gaming also live on at Hagley Library. Record Group 11, the 'Solid State Research Division records, 1899-2001' of our David Sarnoff Research Center records (Accession 2464.09) includes the papers of Joseph A. Weisbecker. Weisbecker’s papers include documentation of his work at RCA and Komputer Pastimes; they include research notes, correspondence, press clippings, prototypes, manuals, publications, patents, and photographs. These records also contain cassette tapes that preserve early RCA games, including games developed by Joyce Weisbecker.

Joseph Weisbecker’s papers have been partially digitized for browsing in our Digital Archives; the digital collection also includes files extracted from these cassette tapes found in Weisbecker’s collection. The video clips of gameplay were provided by Kevin Bunch working from binaries converted from tapes by Andy Modla and Marcel van Tongeren.

Researchers using this collection and others at Hagley Library include Dr. Elizabeth Bader, whose 2024 dissertation “Gaming Culture: Intellectual Property, Capitalism, and their Impacts on the Culture and Gendering of Video Games 1970-1995” explored the early history of video game culture. Badger was inspired to undertake this research based on her own experience with gaming and video game culture, noting the widespread prejudice against video games, and the sexism within gaming culture.

The collection has also proved valuable to Kevin Bunch, an independent researcher of video game history, whose research into RCA in the 1970s for a book project on book about the history of RCA and videogames also included interviewing Joyce Weisbecker.

Skylar Harris is the Digitization and Metadata Coordinator at Hagley Museum and Library