If you pay some attention to the business & economics press, you’ll frequently see apocalyptic warnings about the impending impacts of automation and robots on jobs in the 21st century. There has already been substantial automation of manufacturing in the United States over the last several decades and we are seeing more examples around us, especially in the service sector: self-checkouts in supermarkets are becoming common and many companies are developing driverless vehicles.

We don’t yet know what the impacts of these coming technological changes will be. One approach is to look at how technological changes have impacted jobs in the past, which is the topic of my PhD thesis.

To provide historical evidence for the effects of technology on work, I look at how the quality of jobs has changed in historical instances when companies have introduced new technology. Most people have a rough sense of what constitutes a “good job”: good pay, decent conditions, reasonable hours, preferably some flexibility about when, how, and where we work, and a boss who isn’t overbearing or controlling. I have turned this intuition into a formal approach, using evidence about workers’ concerns in strikes, petitions, union organizing, and wage premiums to derive eight components of historical occupational quality.

During my work on an Exploratory Research Grant at the Hagley Museum & Library last summer, I gathered archival sources for one of the case studies in my thesis: the massive technological shifts in American transportation during the late 18th and 19th centuries. In under a hundred years, Americans shifted from traveling in horse-drawn carriages on poorly maintained roads to steam-powered rail journeys on a network connecting cities separated by more than a thousand miles.

Many Americans felt this change in lower prices and greater availability of food and manufactured products because improved transportation reduced the cost of shipping. They were also able to travel further and more comfortably. However, the people who experienced the most change from the new technologies were workers building and operating transportation systems.

One potential outcome of technological change is technological unemployment: when new techniques or machines raise productivity per worker and allow companies to produce the same—or more—stuff with fewer employees. There was probably some technological unemployment due to the construction of canals and then railroads, but the main shift in the early 19th century was in the types of jobs available for transportation work.

A major theme of the last few decades is “job polarization” or “hollowing out”. These terms refer to a combination of automation and offshoring eliminating a lot of good middle-class jobs in rich countries like the United States. By contrast, the 19th century was a period of what “job stratification”: increasingly complex transportation systems required more division of labor, which meant greater differentiation in the quality of jobs. This created a middle class, but also substantial differences in the quality of work and the quality of life between those at the top and those at the bottom.

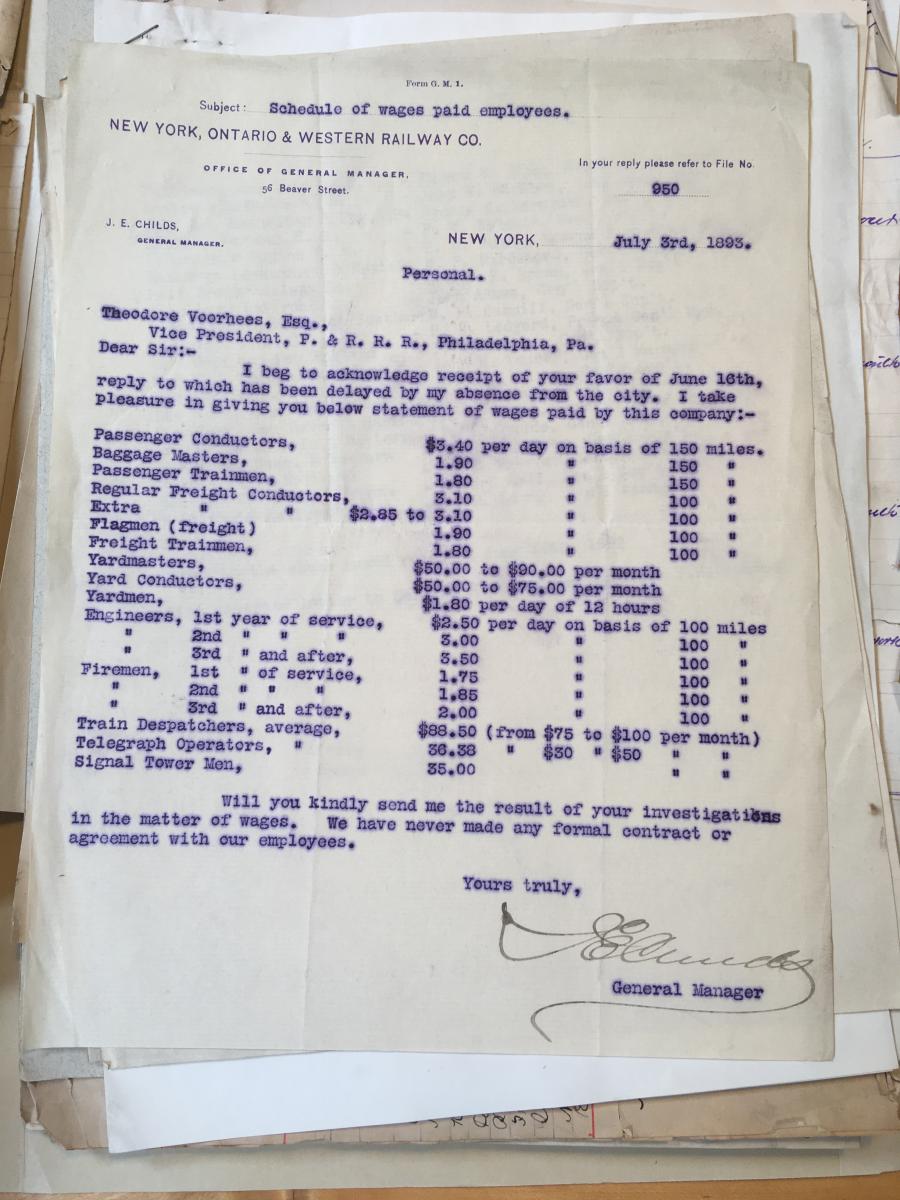

We can illustrate this tangibly: roads were maintained with some combination of unskilled laborers and a few skilled workers like masons and carpenters. A stagecoach company would employ drivers, perhaps stable boys, and provide work for independent blacksmiths and carpenters to shoe the horses and maintain the vehicles. The image below illustrates the increase in a variety of jobs on railroads by the later 19th century—and this document doesn’t include the profusion of white-collar employees that railroads needed for back-office operations.

These jobs were very different from each other: clerks on the Pennsylvania Railroad would earn more than blue-collar workers of comparable seniority, and they had safer working conditions. Surviving occupations (railroads still needed unskilled laborers for construction) tended to change relatively little, but there was much greater inequality of jobs.

Job stratification is one potential outcome of technological change, and it can accompany technological unemployment. If the impending wave of automation is unchecked by regulation or labor organizing, we should not be surprised if it produces both consequences, and a political response may follow.

Benjamin Schneider is a PhD Student at the University of Oxford.