What is your money worth—and how do you know?

Today we are surrounded by many kinds of elaborate price indexes that tell us whether our paycheck or savings account can still buy what it could last year. Unions refer to price indexes when negotiating for wage increases. Newspaper articles routinely mention “purchasing power” and the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index. We expect our employers to offer cost-of-living adjustments to meet inflation. But how did workers in the 19th century, before these numbers were available, deal with the unstable dollar?

To answer that question, I looked at wage negotiations in the railroad industry between the 1870s—a decade before the Bureau of Labor Statistics was created in 1884—and the 1920s, when these statistics had come into more common use. These documents help us see how workers argued for raises, and how price indexes influenced those arguments.

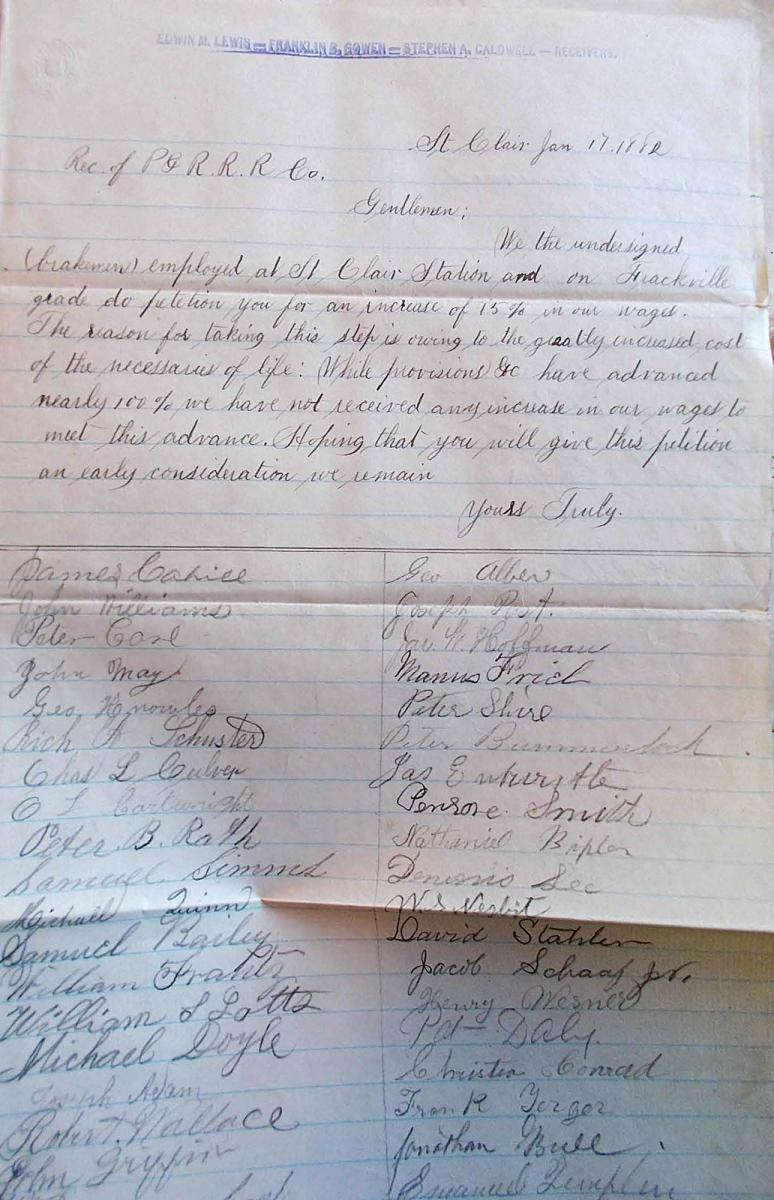

For instance, on January 17, 1882, a group of brakemen working at the St. Clair Station on the Pennsylvania & Reading Railroad submitted a petition to their employers asking for a 15% raise in pay. “The reason for taking this step,” they wrote, “is owing to the greatly increased cost of the necessities of life. While provisions &c. have advanced nearly 100% we have not received any increase in our wages to meet this advance.”

The St. Clair brakemen justified their request based on prices at their local retailers, not official statistics. But their petition demonstrates a keen awareness of local cost of living, and an attempt to turn their experience of those prices, accurate or not, into an argument for a wage increase.

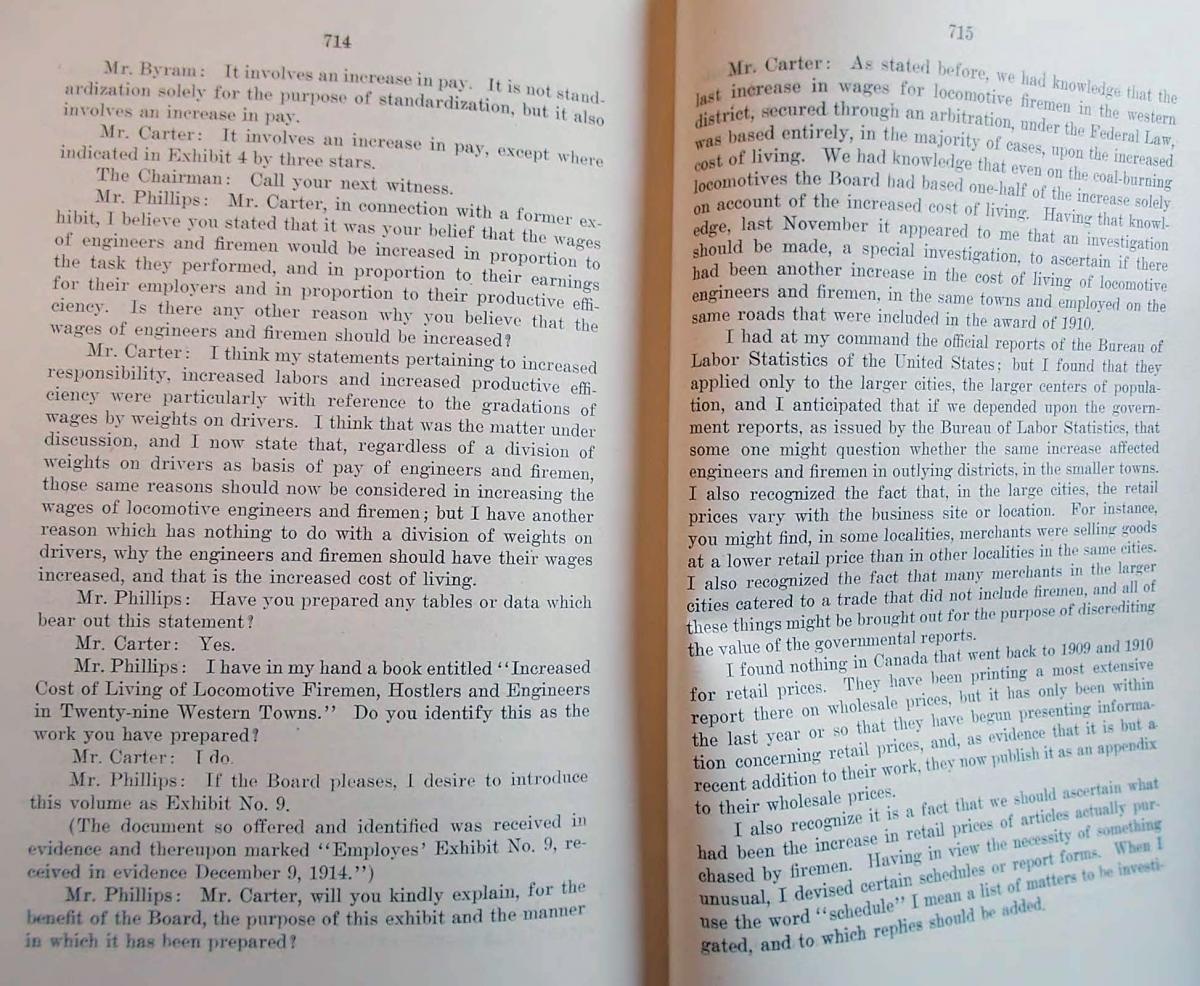

While laborers and their representatives continued to invoke the cost of living when angling for a raise, the negotiations had changed substantially by the 1910s, when price statistics and labor unions were more widespread. Extracts from a 1914 arbitration hearing between the western railroads and union representatives show that both workers and employers attempted to use these figures to their advantage.

The participants had a lengthy discussion of the reports of the Bureau of Labor Statistics—and their shortcomings. One witness points out that they applied “only to the larger cities,” not smaller towns, and that they failed to capture the differences in prices across localities in the same city.

As the brakemen’s petition shows, workers did not need an index to know that the value of their money fluctuated, and they were willing to use this knowledge when confronting their employers. But the arbitration hearing suggests that statistics did not solve the problem.

While price indexes gave more comprehensive information, they remained tied to other factors like business conditions, unemployment rates, and union density. Price indexes signaled the rise of a new cadre of statistical professionals using systematic methods on a national scale, but they did not always align with how workers experienced prices in a particular place—something you might contemplate when you get your next paycheck.

Sebastian Teupe is Junior Professor of Economic History at the University of Bayreuth in Germany.