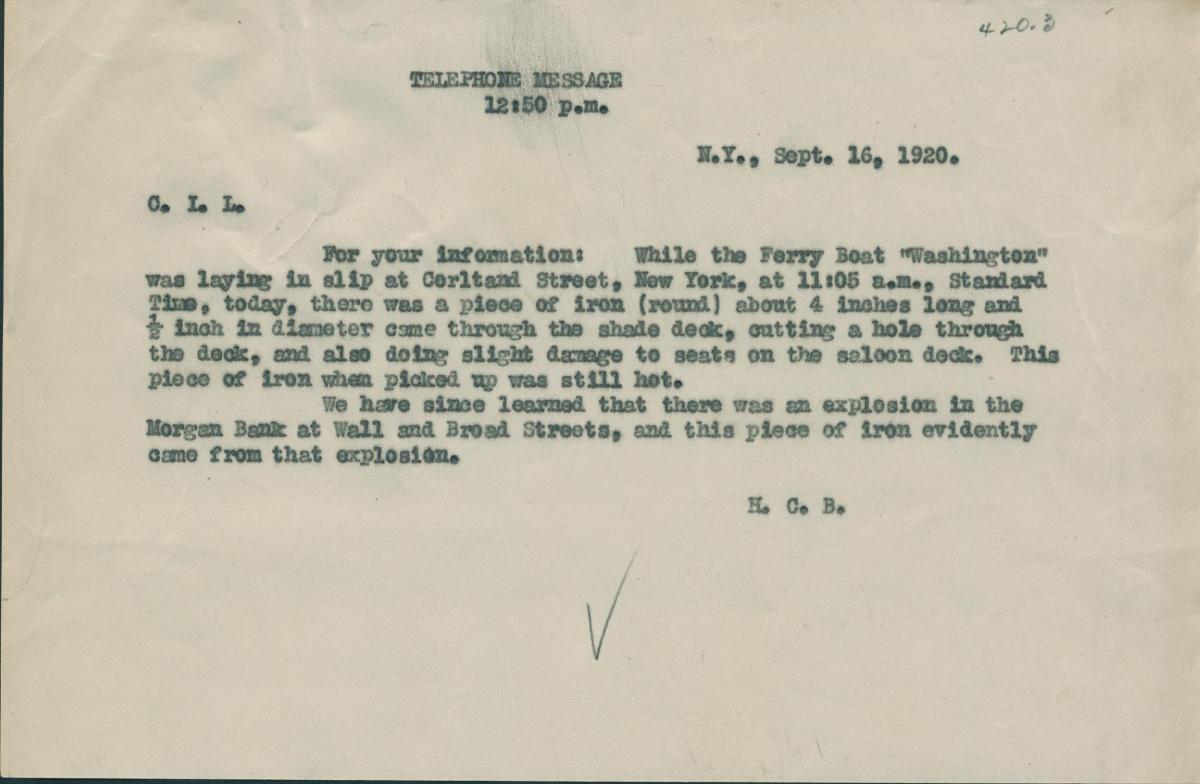

On September 16, 1920, a telephone message from Callender I. Leiper, the Pennsylvania Railroad’s New Jersey Division Superintendent, explained that a piece of round iron came flying through the shade deck of the ferry boat Washington as it lay in the slip at Cortlandt Street in New York Harbor. The piece of iron, described as four inches long and a half-inch thick, cut a hole through the deck and damaged some seats on the saloon deck. When the boatman picked up the iron, he described it as “still hot.” The end of the message cited the source of the mysterious piece of shrapnel:

We have since learned that there was an explosion in the Morgan Bank at Wall and Broad Streets, and this piece of iron evidently came from that explosion.

The explosion referenced was the infamous Wall Street bombing, the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil until the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. The culprit is still officially unknown, but numerous investigations have credited a group of anti-government Italian anarchists who were also connected with a series of similar bombings across U.S. cities in 1919.

This bombing, however, targeted the center of American capitalism, and largely sought to wreak havoc on the general public, regardless of wealth or social status.

The perpetrators carried out the heinous act using a single horse-drawn wagon carrying 100 pounds of dynamite. In addition, the anarchists loaded about 500 pounds of heavy iron sash weights in the wagon for use as shrapnel, one of which became the subject of Superintendent Leiper’s telephone message.

Parking the wagon in front of the headquarters of J.P. Morgan & Co. near the corner of Wall and Broad Streets, the lunchtime crowd barely noticed an unidentified assailant scurrying from the scene, leaving only the wagon and an unsuspecting horse. At 12:01 p.m., the wagon exploded, sending heavy shrapnel ripping through the crowd outside the Morgan building.

Witnesses described the noise produced by the explosion as “enough to knock you out by itself.” Shrapnel reportedly soared as high as the 34th floor of one nearby building. The piece of iron that hit the ferry boat Washington traveled nearly three-quarters of a mile while miraculously evading every building in its path.

Within moments, thirty people were killed, most of whom were brokers, stenographers, clerks, and messengers. Another eight people died as a result of injury, and 143 suffered non-fatal injuries. The heavy shrapnel caused about $2 million in property damage to surrounding buildings. Immediately after the explosion, shattered glass plummeted onto the streets, causing significant injury to anyone caught in its path, while the inside of the Morgan building resembled a war zone.

Incredibly, Wall Street reopened the following day, exhibiting a bold defiance to those who tried to spread terror at the heart of American Capitalism. To this day, damage from the shrapnel can be seen on the Morgan building’s marble edifice.

The brief memo from Superintendent Leiper highlights only a miniscule byproduct of the total devastation wrought by the Wall Street bombing. Truly, the Pennsylvania Railroad was notorious for documenting almost every aspect of its operational procedures and incidents, regardless of magnitude. This is apparent in the General Manager’s files from PRR’s New Jersey Division operations.

For more information on the Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s New Jersey Division records, and when they will be available for research, please contact askhagley@hagley.org.

Clayton Ruminski is the Technical Services Archivist in the Manuscript and Archives Department at Hagley Museum and Library.