My dissertation examines how US naval officers' political values influenced the country’s path towards civil war. The antebellum era was a period of intense partisanship. One of the things I’m trying to determine is whether individual beliefs about territorial expansionism were a source of division in the officer corps, and how these beliefs affected leaders’ decisions. These questions were particularly salient during the Mexican-American War when the navy helped seize land that could add slave territory to the union.

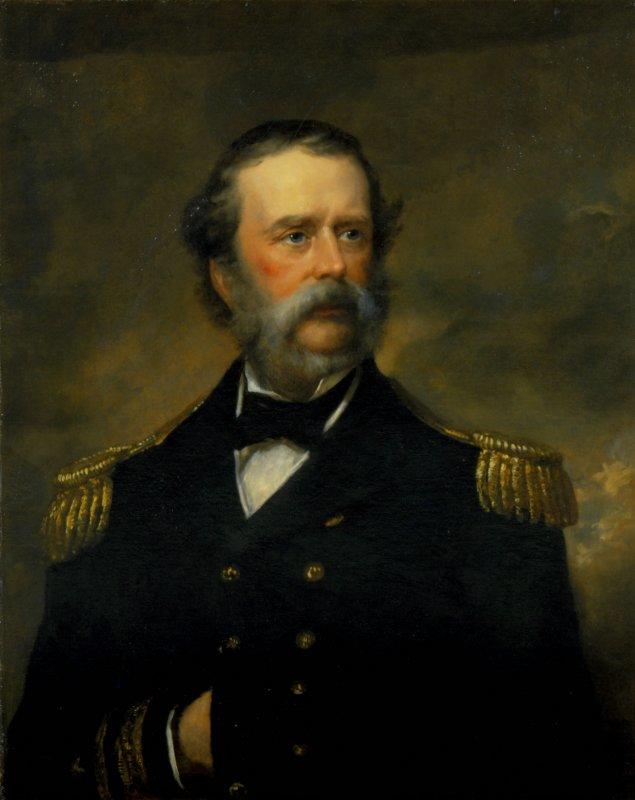

I came to Hagley with the assistance of a Henry Belin du Pont Research Grant to study officers’ opinions about the war by looking at their personal letters. When fighting broke out in 1846, Samuel Francis Du Pont (later a prominent Civil War admiral) was a sociable and popular commander in the navy. As the trouble with Mexico escalated, his fellow officers wrote to him candidly discussing their thoughts about the conflict.

Officers’ support for the war was mixed, but interestingly, Du Pont’s letters reveal that even as the tensions with Mexico rose, most officers were more focused on a possible war with Great Britain over the ongoing boundary dispute between Oregon and Canada. Commander Henry W. Ogden even claimed that conflict with Mexico “has doubtless been brought about by England, as a stroke of diplomacy, to create a diversion in her own favour” in the Oregon negotiations.[1] Lieutenant John S. Missroon went further, predicting that in the war with Mexico, Britain would temporarily take possession of California “for safe keeping,” so Americans couldn’t gain control of Californian ports for the coming war over Oregon. [2] To the officers, war appeared inevitable in the face of scheming British imperialists.

On the surface, the evidence suggests that officers weren’t overly concerned about the pro-slavery aspect of war with Mexico. Their preoccupation with Oregon may have partly been because the Royal Navy was a more dangerous opponent than the Mexican Navy. But recent scholarship shows that Southern elites saw war with Britain as a threat to American slavery—and supported the navy as a defense.[3] So while most officers may not have had a direct interest in the expansion of slavery, they had common concerns with their pro-slavery colleagues that almost certainly helped them see eye to eye in the years of growing tension leading to the Civil War.

[1] H. W. Ogden to S. F. Du Pont, Jan. 22, 1846, W9-4540, Samuel Francis Du Pont Papers, Hagley Museum & Library.

[2] J. S. Missroon to S. F. Du Pont, Feb. 20, 1846, W9-4543, Samuel Francis Du Pont Papers, Hagley Museum & Library.

[3] Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 7.

Roger Bailey is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. His dissertation, “A Crisis of Identity: Sectionalism and the US Navy Officer Corps, 1815-1861,” studies the involvement of US naval officers in the colonization of Liberia, conflict with Mexico, exploring expeditions, anti-filibustering operations, transatlantic slave trade suppression, and the secession crisis.