How campaigns are funded has long been a concern of Congress, particularly when it came to political parties, political action committees, unions, and other groups. In 1910, the Federal Corrupt Practice Act was enacted and amended in 1911 and 1925. It sought to establish campaign spending limits for political parties in congressional general elections.

Political parties were expected to publicly disclose spending, but candidates were not held to the same expectations. In its original form, the Publicity Act, as the Federal Corrupt Practice Act was also known, was rarely enforced and generally weak.

The stronger version following the 1925 amendment, still had its weaknesses. It did not include a regulatory authority to establish a manner of reporting or disclosure to the public, there were no set penalties for failing to comply, and enforcement was left up to Congress, who rarely acted.

Additionally, the Act did not regulate total contributions, which encouraged parties and donors to set up multiple committees to make several donations all under the maximum amount allow, in order to avoid the law’s limits.

In 1928, the House of Representatives established the Special Committee to Investigate Campaign Expenditures, and similar committees became recurring features of each election year beginning in 1944. The committee was charged primarily with the task of overseeing the political campaigns of candidates for elections, particularly investigating campaign contributions and expenditures in both the primary and general elections, violations of federal election laws, and other matters that the House might consider drafting necessary remedial legislation.

Candidates were provided with information on federal election laws, and the committee collected campaign finance information from a variety of sources. The committee occasionally held public hearings over potential disputes and to gain information, which is where NAM fits into this picture.

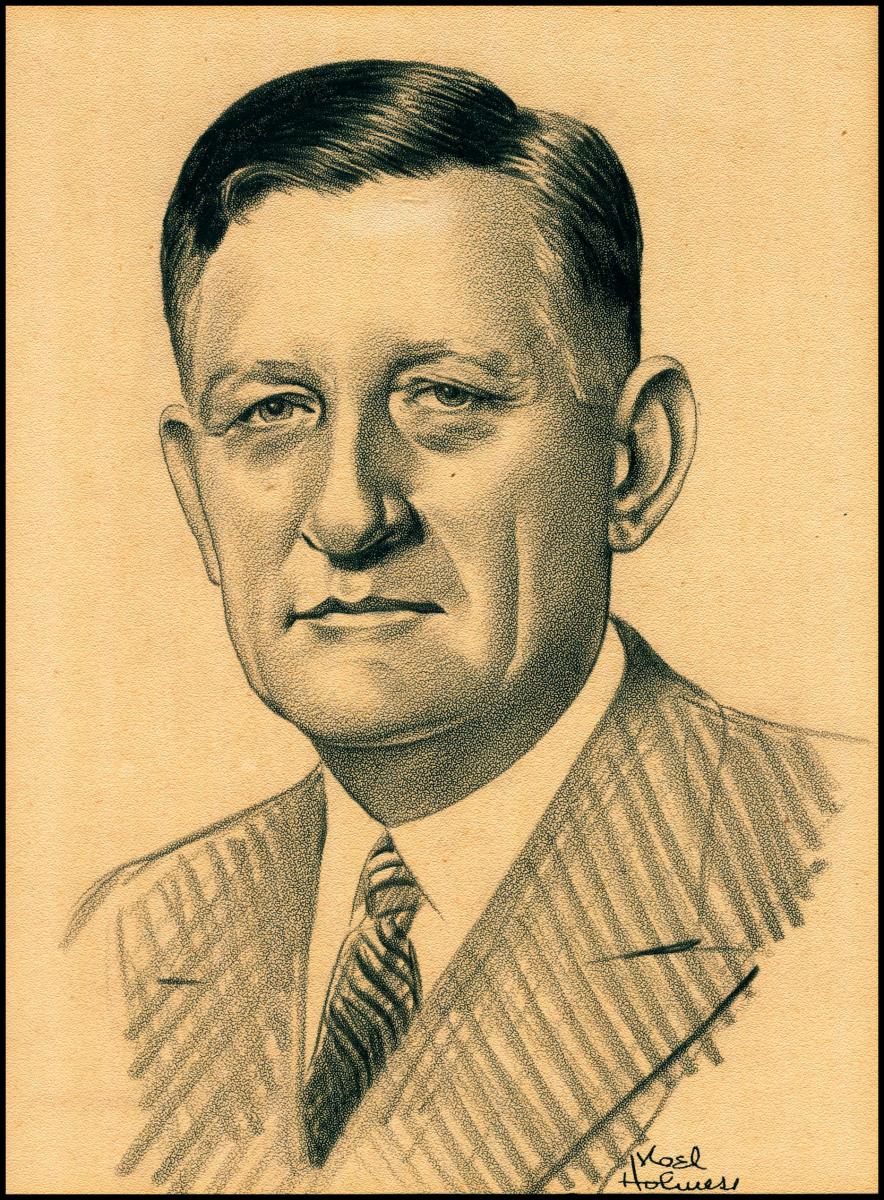

In 1944, NAM was asked to testify before the House Campaign Funds Investigating Committee. President Robert M. Gaylord appeared before the committee on August 31, 1944 for nearly two hours answering questions.

He asserted that “the National Association of Manufacturers is not a political organization or committee; it does not make any contributions whatever to any such political organizations or to any candidates for public office, nor does it endorse or support any political party or candidate.” Instead, NAM and its National Industrial Information Committee, strictly provide educational materials in regards to politics, specifically Congressional voting records for specific issues of interest to members.

Following the House committee’s report, the general counsel for NAM, Ray S. Smethurst, wrote a memo about an Associated Press story on the report: “While the body of the report undoubtedly includes NAM in describing certain general characteristics of the various organizations investigated, and to that extent may create an unfair implication, I doubt that the report as a whole would justify any formal protest by NAM to the Committee.”

Some of the other organizations called to testify included Congress of Industrial Organizations’ Political Action Committee, National Citizens Political Action Committee, Union for Democratic Action, and Communist Political Association. The report stated that all the organizations investigated in one sense or another did engage in political activity, but Smethurst argued the term “political activity” is extremely broad and it would be futile to contest NAM was unfairly included. Instead, he “would rather see the issue drawn if and when legislation is drafted.”

Ashley Williams is the project archivist for the NAM Collection at Hagley Museum and Library.