“Cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the dogs of war”

Far from being the ferocious beasts described in Shakespeare’s famous line, the dogs depicted in the war-time imagery here in Hagley’s Audiovisual Department are loving symbols of home and fidelity. I recently came across an excellent example of this in the form of a series of images published by the Hercules Powder Company during World War I.

The Hercules Powder Company, which was formed in 1911 after an anti-trust ruling against the E.I. du Pont de Nemours "powder trust", published illustrated calendars as a part of its advertising efforts. These calendars frequently depicted country hunting scenes in which dogs were prominently featured as the hard-working companions of their owners. When the United States entered World War I, it was natural that Hercules would use dogs as the protagonists of its war-time imagery.

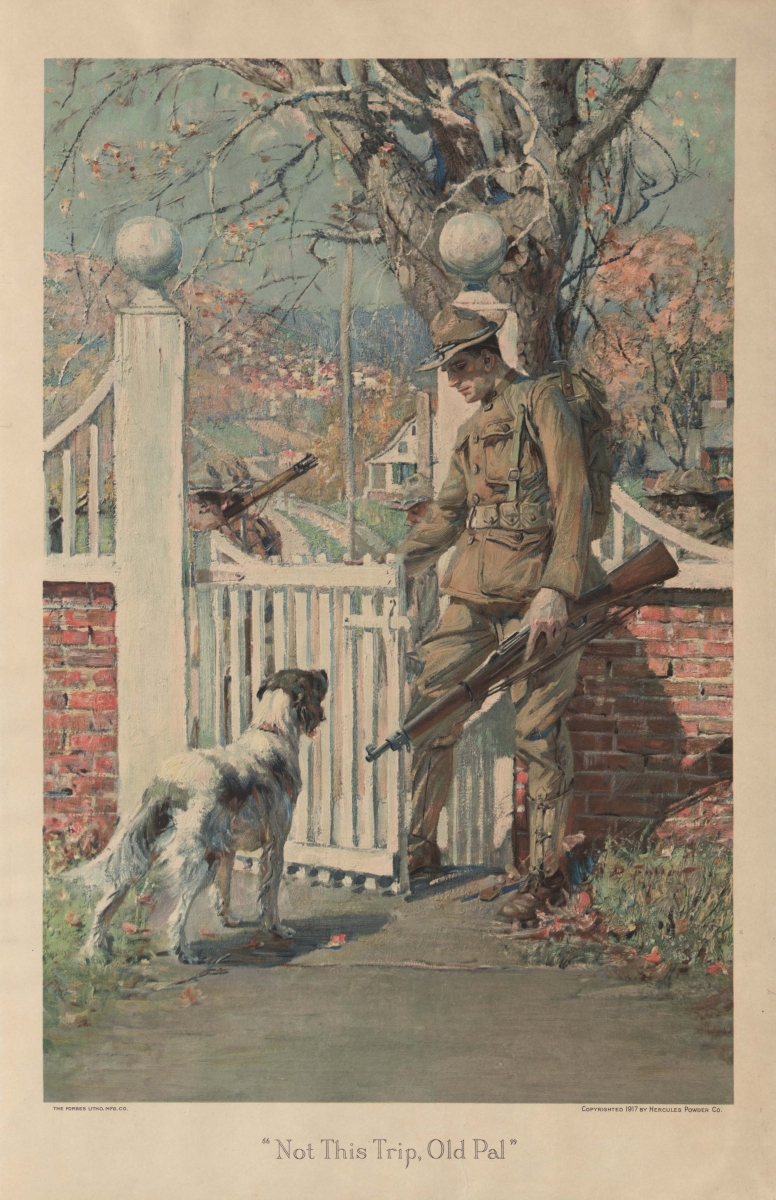

The three World War I era Hercules prints that we have here at Hagley, made from paintings by the artists Arthur Davenport Fuller and Norman Price, create a sort of tripxych that spans the duration of the war. All three images are painted with the same white picket fence and tree in the backgrounds and, most importantly, feature the same dog. This imagery, in addition to imbuing the images with a sense of Americana, clearly identifies the images as portraying one family over time. In the first image, published in 1917, a soldier tells his dog “Not This Trip, Old Pal”, as he leaves to join the steady stream of other men in uniform heading for war. The center of the tripxych, rather evocatively titled “Bagged in France”, depicts the soldier’s parents opening a crate from France containing a portrait of the soldier and a German helmet. The dog, as the soldier’s representative at home, sniffs these items as the soldier’s parents hold them out to him for inspection. The last, published around 1920, is entitled “A Surprise Party.” In it, the soldier is met by not only his dog, but a litter of healthy, happy puppies as a pair of children look on. The soldier is instantly met with the happiness and prosperity that his fighting was able to ensure.

In these images, dogs afford the artists a two-for-one use of space. Because they are both brave hunting companions and loving family members, dogs become dual symbols of both the soldier and the soldier’s family and remind the viewer of the duties of each: the duty a soldier has to fight for his country and the duty of those at home to loyally support him.

As what is perhaps a testament to the strength with which this sort of imagery speaks to the American psyche, a photograph in our Conrail collection from the World War II era echoes the exact sentiment of the “Not This Trip” image. In the early 1940s, Alan F. Sozio of the New York Herald Tribune snapped a noir-like photograph of a dog sitting on a train platform and staring down the tracks in a pose of longing that rivals that of Humphrey Bogart’s in Casablanca. The super-imposed text reads “The greatest guy in the world was aboard that draft train.” Here, as in the Hercules imagery, the viewer is given the impression that the dog would fight if allowed (and certainly many dogs have been used in war service), and will wait loyally for his soldier to return. As in the Hercules imagery published over twenty years earlier, the image of the dog serves as a bridge between the soldier and the home front.

Lynsey Sczechowicz is the Audiovisual Reference Archivist at Hagley.