Can bricks be carved, in other words, shaped with tools to create architectural ornament, the way stone is carved? It certainly seemed so: I noticed carved brick on several Boston area buildings that dated from the late 1870s and early 1880s. This decoration is easily mistaken for, and inaccurately called, architectural terracotta. Since nothing had been written about it, I decided to research the topic. How was this ornament made, and why was it adopted?

I had more success in answering the second question than the first. In the 1870s, some young British architects began to design in a new architectural style that came to be called Queen Anne. Rather than the poly-chromatic stone of the Victorian Gothic style (think, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts building), brick was their preferred façade material, for the walls as well as for decoration.

Carved brick is actually an old form of architectural ornament, made by carving specially-made bricks. For example, it is found on buildings in northwest Belgium and in England, from the Renaissance period through the 18th century. But the technique had died out in the nineteenth century. So when the Queen Anne architects called for it, they revived a lost art.

Soon American architects adopted the style and also carved brick. In the late 1870s, Queen Anne-style houses, some with carved brick panels and accents, began to appear in the houses of Boston’s fashionable Back Bay neighborhood, then under development. In the U.S., as in England, the technique was unknown, but professional carvers quickly began to work in it. It seems carved brick was most popular in the Boston area: I have searched of all instances of this decoration from the heyday of Queen Anne, the late 1870s and 1880s, and there are few outside of the Boston region.

The second question, how was this made, proved harder to answer. One of the surprising features of surviving examples is how crisp they are, despite years of exposure to weather and air pollution. Architectural conservators warn that removing the hard, outer skin on brick damages it and accelerates its deterioration. Since this has not happened to the carved bricks, one assumes they were made with a special kind. Indeed, one can observe that in many cases, the carved bricks are different from those surrounding them in a wall.

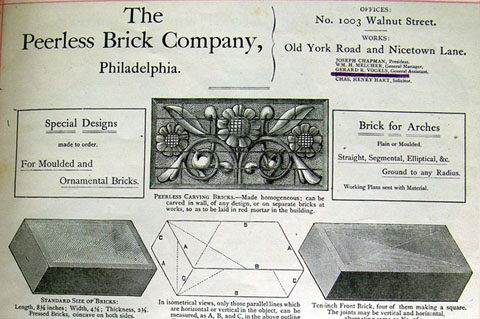

Fortunately I was able to find information on one of the manufactures of carving brick in Hagley’s collection of trade catalogs. Trade catalogs are ephemeral material, and Hagley has a marvelous collection of them, for all sorts of products. A lead to a manufacturer came from a contemporary architectural periodical: in response to a query about where one obtained bricks for carving, the editor wrote that Peerless Brick Co. of Philadelphia made carving bricks, which were the “ones generally used in Boston and elsewhere.” Hagley has a copy of a Peerless Brick Co. catalogue, Diagrams of molded, ornamental and colored bricks… (ca 1879-80). And there, on page 7, is a small illustration of “Peerless Carving Bricks.” On the back cover, under the heading Carving Brick, is the announcement, “We call the attention of Architects to our Extra-fine Carving Brick, made especially for this purpose—being homogeneous in texture and rich in color.” Having this confirmation that special bricks were made for carving was extremely useful. And that I could get it was miraculous: apparently Hagley owns the only copy of this catalog in a library open to the public.

So, I could write that special bricks were made for this decoration. The bricks could be built into a wall and carved in place, or formed into panels and carved in a workshop, and then installed in a wall. But I could not discover the names of other companies that made these bricks. And most regrettably, I could find very little information about the recipe for the bricks or process by which they were manufactured (trade secrets?). I presented my findings at the Fourth International Congress on Construction History in Paris in 2012, and my paper, “Against Replication: Carved Brick at the Dawn of the Terracotta Age,” was published in volume 2 of the Congress proceedings, Nuts & Bolts of Construction History.

It would seem that there should be examples of carved brick in the Philadelphia region. But only two from the Queen Anne-period have turned up, one of which has been demolished, the other, an interior fireplace – not something I can see.

Now that you, dear reader, have an idea of what this material is like, I’d appreciate it if you would contact me if you notice it, and let me know where.

Sara E. Wermiel is a historic preservation consultant and historian of technology. She received a doctorate from MIT in the history of technology and urban history.