Tasked with sharing my research via newsletter posts, I sometimes choose models based upon when the article will be published. With over five thousand models to choose from, I must narrow it down somehow! In this specific case, the post will appear near March which includes Women’s History Month and St. Patrick’s Day. I also began writing this around Valentine’s Day. Could I find a patent model with an intriguing story that connected a woman inventor with Ireland all the while telling a love story? Challenge accepted!

Allow me to present Mary Melville and John Kidd’s Improvement in Culinary Pots!

Sure, this model may not look like much, but, like most of the patent models in Hagley’s collection, what it lacks in aesthetics it makes up for in backstory.

The inventor, Mary Louise Iucho (1843-1914), was born in Kentucky. Her father, a German immigrant, taught music and appears to have been rather wealthy though the source of that wealth is unknown. He later moved to New York City where he taught piano at the prestigious Abbott Collegiate Institute for Young Ladies. Mary and three of her sisters also attended the school. Mary continued her education by attending the Brooklyn Heights Seminary whose distinguished female alumni include noted writers, jurists, educators, and progressive social reformers.

Mary eventually married a man named Augustus “Gus” Melville (1841-1889). Like her father, Gus seems to have come from wealth as they were listed in the New York State census a few years after their marriage living in a home with a daughter, a cook, and two nurses. Somehow, in between having three more children and burying one of them, Mary found time to invent this set of cooking pots. They were designed to nest within the circular opening in the top of a cooking stove.

But she didn’t invent alone. Her co-patentee was John Samuel Kidd (1839-1902), and he may have been her brother-in-law. Mary’s sister, Caroline, married William H. Kidd, a wealthy liquor and wine dealer. Together, Mary and John would earn another patent two years later as well as a reissue of this patent.

Around this time, John was listed in the 1875 New York State census as a “boarder” living in a home with Mary, her parents, her three children, and two servants. But where was Mary’s husband? Gus Melville was not listed in the house or found in the census though they had welcomed their fourth child just two years earlier in 1873. Did he abandon her? Did they divorce? While we may never know, one thing is for certain, love blossomed between her and her fellow inventor. In 1878, Mary and John were married. And John’s business prospects had blossomed as well.

The Kidd family had immigrated from Ireland around 1848 and started out in Cincinnati, Ohio. John’s older brother, George W. Kidd (1835-1901), became a whiskey distiller and eventually a partner in a Cincinnati distillery that also opened a branch in New York City. When George moved to the city to run the distillery around 1868, he brought John along. By the time Mary and John married, John was a distiller and a commercial merchant within the booming Kidd family liquor business.

John and Mary next appeared in the 1880 U.S. census as living in Peoria, Illinois with “distiller” listed as John's occupation. At that time, Peoria was considered the “Whiskey Capital of the World.” Peoria was also the headquarters of the Western Export Trust, nicknamed the “Whiskey Trust” and the “Whiskey Pool.” This “trust” was an affiliation of distillers who conspired to regulate production and thereby control prices. Perhaps John went there to represent the interests of the Kidd brothers. The brothers later ran afoul of the trust by producing too much whiskey. Though the scandal made the papers nationwide, George angrily refused to pay the fines levied by the members.

By 1881, John and Mary moved to Des Moines, Iowa where the Kidd brothers operated one of the largest distilleries in the country. Their timing was awful seeing as prohibition advocates in Iowa were gaining political power. The following year, the state passed a constitutional amendment barring the production of alcohol for anything other than “mechanical, medicinal, culinary, and sacramental purposes.” Though John managed to keep the distillery operating during this ongoing political and legal wrangling, it was later labeled a “nuisance” and shut down. The brothers fought its closing in a case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court (Kidd v. Pearson).

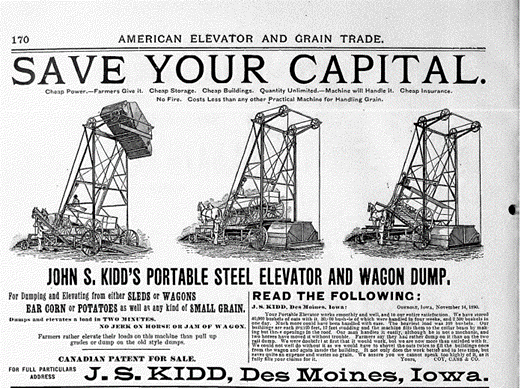

While John campaigned to keep the distillery open, he began working on new inventions. He earned two patents for a machine that dumped wagon loads of produce onto an elevator platform. It seems that his combination dump and elevator was a success as agents representing his invention can be found in newspaper advertisements (see below). He earned nine more patents related to this invention.

In 1901, John and Mary received one last windfall from the distilling business. When George died in New York City, he named his brother in his will and the couple received a substantial amount from his estate. Sadly, the will was tied up in litigation for years and John died before it was settled.

So there you have it! An invention patented by a woman who fell in love with her co-inventor from Ireland…with an Irish whiskey connection thrown in for good measure. I’ll have a hard time topping that one for my next post!

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library