Last year, members of the Wright family sold their “Merino Hill” Farm in the southwestern corner of Monmouth County, N.J., after six generations of occupancy. The Wrights were one branch of a family of early Quaker settlers in what was then called West Jersey. Samuel Gardiner Wright (1781-1845) inherited the land when he married his distant cousin Sarah Wright in 1805 and built the new house called “Merino Hill” in 1810. As the name indicates, Samuel G. Wright, like E. I. du Pont, participated in the Merino sheep craze, but besides being a farmer, he was a general entrepreneur and merchant, with a trading business with the trans-Mississippi West, lumbering operations, iron mines and iron furnaces in the Pine Barrens at present-day Lakehurst, N.J., and in Sussex County, Del. Wright also speculated in undeveloped land in Illinois and Missouri, but his many schemes collapsed and contracted in the wake of the Panic of 1837. Subsequent generations at Merino Hill were primarily gentleman-farmers.

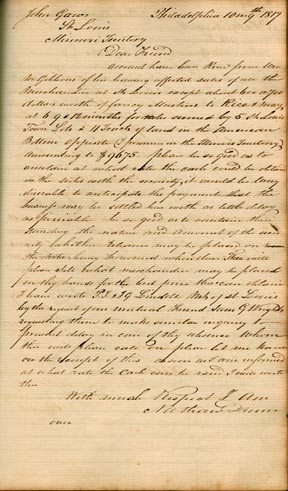

With continuous occupancy, the papers of Samuel G. Wright and his family survived in the nooks and crannies of “Merino Hill,” most folded into neat little bundles and left much as they were when the writers’ estates were finally settled. The papers were gifted to Hagley by two separate generations of the family in three lots in 1979, 1989 and 2013. Together they document activities on the cusp of American industrialization in the 1810s, 20s and 30s. The 2013 gift, the result of a last house-cleaning, fills some of the gaps in the business history outlined in the well-used earlier records. What is most interesting about the new material is perhaps what it tells us by association. Take for example an account book belonging to Philadelphia merchant Nathan Dunn (1782-1844). Part way through, Dunn’s (or his clerk’s) neat penmanship gives way to Wright’s scrawl. Dunn had become bankrupt, and the Quaker meeting censured him and made him assign his property to Wright to settle his affairs and pay his creditors. The volume doesn’t tell what came next. Dunn went to China to recoup his fortune and did so while holding to Quaker scruples and not dealing in opium. He returned to Philadelphia with thousands of artifacts depicting Chinese daily life and culture, which he exhibited in his Chinese Museum, probably the first American attempt to present China in objective, almost anthropological terms and not as a nation of exotics or heathens.

A map that Wright collected, probably because it showed the Santa Fe Trail, over which he traded with Mexico, actually accompanied a government document and shows the Jackson administration’s removal of all Native American to allotments of land west of the Mississippi River.

Wright sent his son, Harrison Gardiner Wright (1810-1885) to the prestigious Burlington Boarding School, the premier Quaker academy in West Jersey. At graduation, instead of yearbook autographs as mementoes, he received an album of poems copied by his classmates in their best hands expressing “Friendly” notions of comradeship.

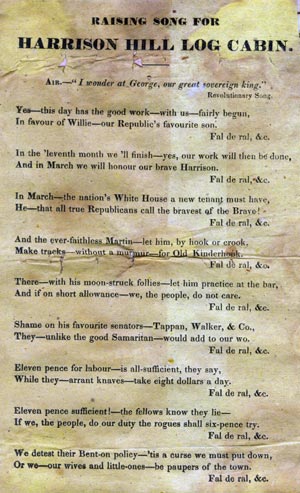

A card from the 1840 “Log Cabin” campaign illustrates Wright’s active role in Whig Party politics, which he capped by being elected to Congress in 1844, only to die before Congress convened.

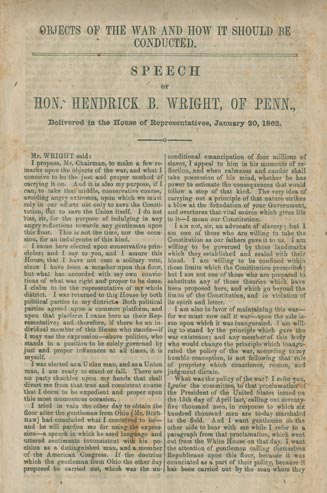

In contrast, a speech by his cousin, Congressman Hendrick B. Wright (1808-1881) drives home the Northern Democratic view that the Civil War was being fought to restore the “Union as it was” and not to abolish slavery.

David Thacher (1767-1830) was a salt-maker from one of the pioneer families of Massachusetts and was bankrupted when the Jeffersonian Embargo and War of 1812 devastated New England’s commerce. He resumed his trade at Tuckerton, N.J., and Wright engaged him to develop a salt-works at Lewes, Delaware, an enterprise that also ended badly.

In contrast, Wright’s agent for his Illinois lands, William J. Conkling (1826-1904), became one of the richest lawyers and real estate dealers in Springfield and doubtless made more money out of Illinois land than the Wright family ever did.

Behind the letters and maps are dozens of stories of success or failure as Americans wrestled with questions of economic and industrial development in a sprawling country far from the placid landscape of Merino Hill.

Chris Baer is Assistant Curator of the Manuscripts and Archives Department at Hagley Museum and Library.