The funny thing about exhibits is that you often know more about their subjects when they close than when they open. Once folks see or hear about an exhibit, new information and objects seem to come out of the woodwork. If there is a bright side to the year-long delay in the opening of Hagley’s new exhibit Nation of Inventors, due to flooding caused by the remnants of Hurricane Ida, it is that it has allowed the curators to include an important addition in the form of a very special patent model that showed up on our doorstep thanks to the keen eye of one of our friends in the collecting community.

It all started last November. A typewriter collector contacted Hagley about examining a few of our typewriter-related patent models. In addition to an amazing collection of important typewriters, he also owns a few models. During his visit, he asked if Hagley was interested in adding to our collection. I explained that while our acquisitions budget is limited, we are interested in models from inventors underrepresented in our collection, such as those from women or Black inventors.

Several months later, he contacted me about an exciting patent model find. Not only was this model from a woman inventor, it was also special for several other reasons. It was the first American patent for an iron, the twenty-ninth patent issued to a woman in the United States, and the oldest known surviving model submitted by a woman. While Hagley didn’t have the means to acquire the model, the collector recognized its significance and bought it for his collection.

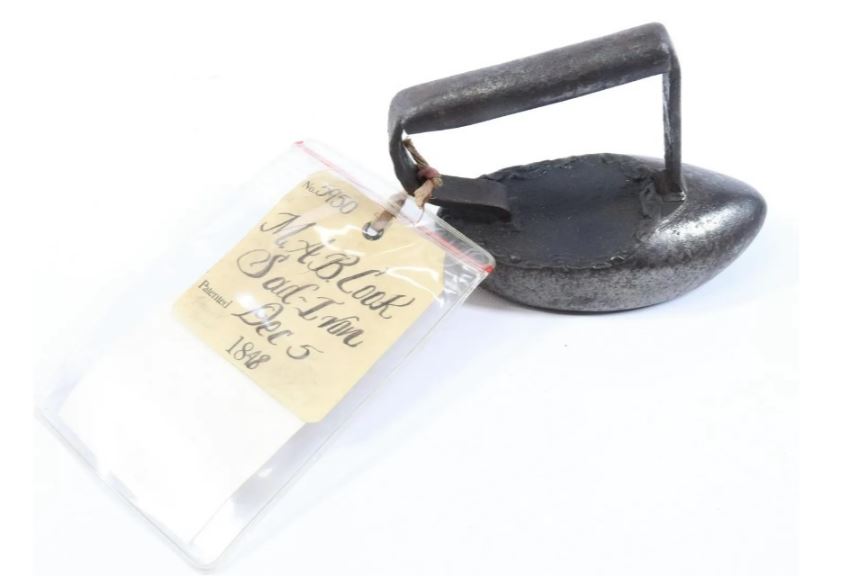

Another month or so later, he offered to stop by Hagley and show us the model. To our surprise, he offered to loan it for display in Nation of Inventors. He wanted to share this important find with the public and couldn’t think of a more appropriate place than in the “Women Inventors” section of the exhibit. Here is a photo:

The inventor’s name is Mary Ann B. Cook. She states in her patent application that she was discouraged by “Common sad-irons [with] only one flat ironing surface.” So, she designed an iron with multiple pressing angles. Much like a Swiss Army knife with many blades, the iron’s flat, curved, and pointed surfaces pressed wrinkles on any part of the garment. Its tapered, elliptical shape created two different heat zones, while the angled handle forecasted modern ergonomics by creating less stress on the user. Plus, when used with starch alone, it applied a glossy sheen to the decorative ruffles in the sleeves and collars of fashionable Victorian clothing. Other irons required that the starch be mixed with wax or spermaceti (a waxy substance produced by the sperm whale), which were expensive and left a greasy residue, making it difficult to remove soils and stains from the delicate folds.

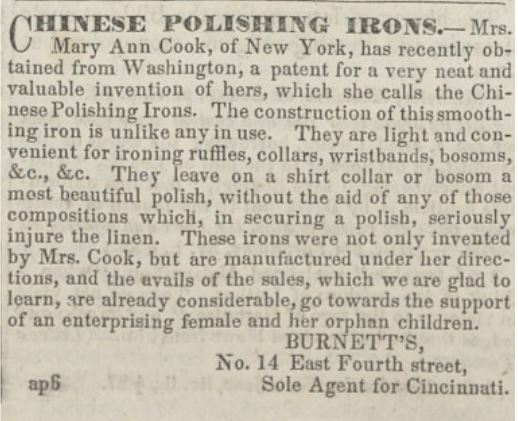

I immediately asked our volunteer researcher, Trudi Koston, to track down any information on Cook. Sadly, she did not find very much, but she did manage to locate a few relevant newspaper advertisements. Many of the inventions represented in our patent model collection never existed beyond the inventor’s imagination. For various reasons—limited investment capital, difficulty in manufacturing, or lack of interest—they simply never made it past the barn or workshop. Clearly, Cook’s irons were manufactured and sold in stores. Retailers advertised that they carried her “Chinese Polishing Irons” in newspapers as far west as Cincinnati, Ohio.

Knowing that several unique irons came to Hagley through the Amram Women Inventors Collection, I searched Hagley’s collections database. And, amazingly, I found one of Cook’s irons (below)! It differs slightly from the patent model in that the handle is less angular, and the patent date is molded into the top of the iron. It is a thrill to match a patent model to one of the objects in our collection and display both side-by-side!

Be sure to visit the patent model and its retail version when Nation of Inventors opens this fall.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library.