Some conservation treatments can be monotonous. Take the process of carefully removing adhesive from the front of a photographic print. This is one step of the preservation of the 1890s industry and site images taken along the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) by William Rau and his assistants. The torn-off remnants of window matting around the image edges requires repeated application of poultices (gels) and damp cotton swabs to remove sticky animal glue without destroying the image. These pictures, which are composed of silver embedded in a thin layer of gelatin, will swell if they are wetted for too long. Small sections must be revisited with warm water and ethanol between drying to take away the tenacious goo.

It is inevitable that details will come to light during hours of cleaning and studying the physical prints and the scenes they depict. The photographs are over 14 x 20 inches, so details such as building signs and ship names are legible in many of them. This information can be used in conjunction with handwriting and typed labels on the backs of the photo mounts to corroborate the location.

These days we have many options when looking for information about locations in photographs. Starting with a web search using a set of descriptive terms is often the starting point. It helps substantially when there is a title associated with an image, but what if there are inaccuracies in that documentation? For this set of images, we have the image itself, but also the original exhibition catalog published by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1893. The catalog lists everything shown in the Chicago Columbian Exposition at the building and displays erected by the PRR to document their accomplishments. Each photo has numerous inscriptions and labels attached to the back and front of the mounts. Their typed titles generally match what is printed in the catalog, but sometimes writing on the photograph contradicts the label. Sometimes there are errors in location and spelling in both the label and the catalog.

In one instance, the original exhibition catalog lists an image called “Briar Hill Iron and Coal Co. Briar Hill, PA”. Handwriting on the back of the photograph includes “PYTARR” (likely Pittsburgh Youngstown Ashtabula Railroad) and “67 miles from Pitts(burgh)”. This should be Brier Hill, near Youngstown Ohio. A historical marker in Trumbull County Ohio mentions Ohio Governor David Tod’s Brier Hill furnace. The Historical Marker Database has been quite helpful in gathering tidbits about some of these industries and their locations. David Tod was Governor of Ohio during the Civil War and he owned iron ore bearing land near Youngstown.

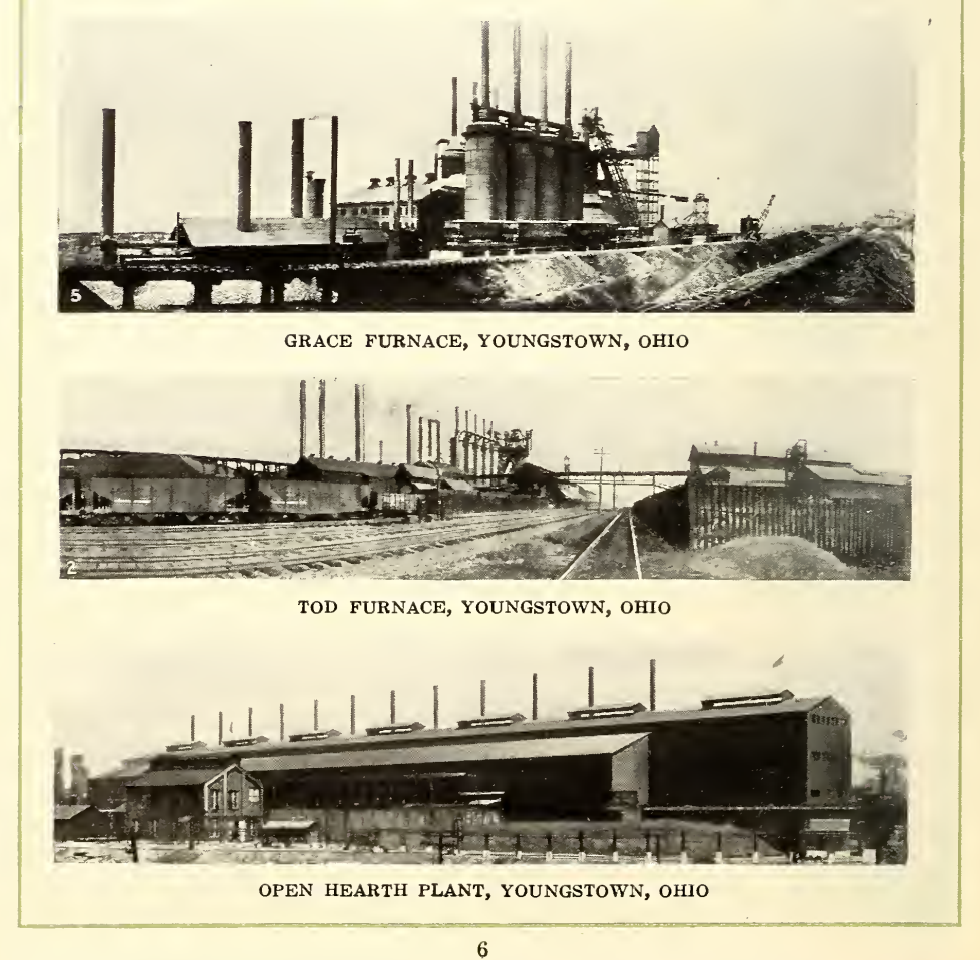

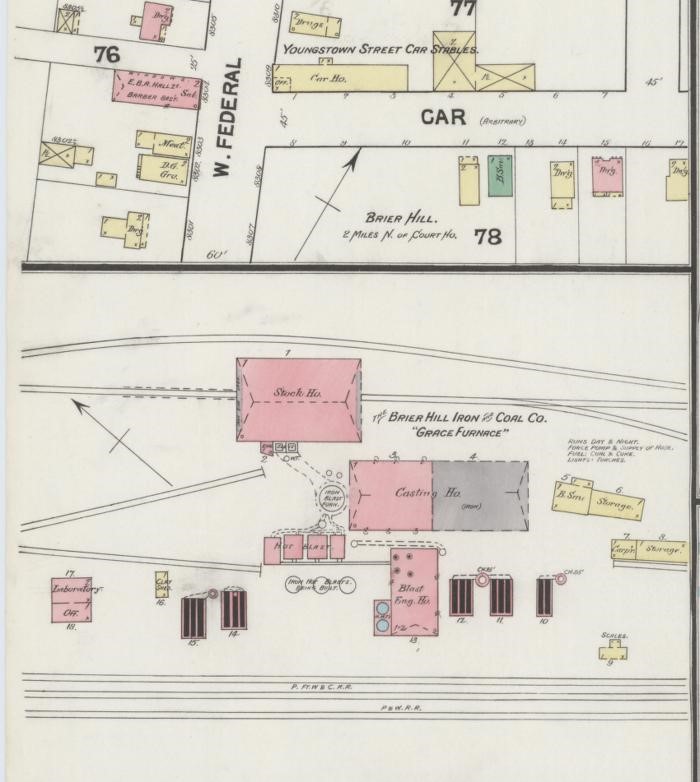

One source, The Brier Hill Reference Book, Brier Hill Steel Co, Youngstown, OH, 1919, depicted several sites, including Tod Furnace and Grace Furnace. Additional evidence was gathered from the Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Mahoning County Ohio, in 1889, which included the building site plans for both Grace and Tod Furnaces. The number and arrangement of the blast furnaces and buildings of Grace Furnace seem closest to those in the photograph. However, it was still under construction, and some elements might have changed.

The 1882 History of Trumbull and Mahoning County mentions Grace Furnace #1 and Grace Furnace #2, erected in 1859 and 1860. Since the fire insurance map indicates that some parts of the plant were incomplete in 1889, there may have been yet another factory erected or improvements that were ongoing at the time of Rau’s visit. Historical accounts also mention Grace Tod, the daughter of Governor Tod, so naming furnaces after family members must have been a practice.

It is understandable that inaccurate locations might have been attributed when travelling along the railroad where many of the industries straddle the Ohio River, and at the intersection of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. The steel industries typically owned interests in multiple states, including Ohio and Pennsylvania, as did Brier Hill. Over decades it expanded and acquired mines in the coal seams of the Mahoning River region and by 1919 it had offices in 10 states. It also is natural to assume that verbal communication was part of the breakdown. Slips of paper were used to label negatives before they were developed later in the evening. The photographs were printed upon return to the studio in Philadelphia, and were likely done in haste. At least some photographs intended for exhibition were being taken after the Columbian Exposition had opened. This photographic excursion wound its way from New York, through New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, in the time span of a few months. There probably weren’t many location signs along the railroad tracks either!

Laura Wahl is the Head Conservator at Hagley Museum and Library