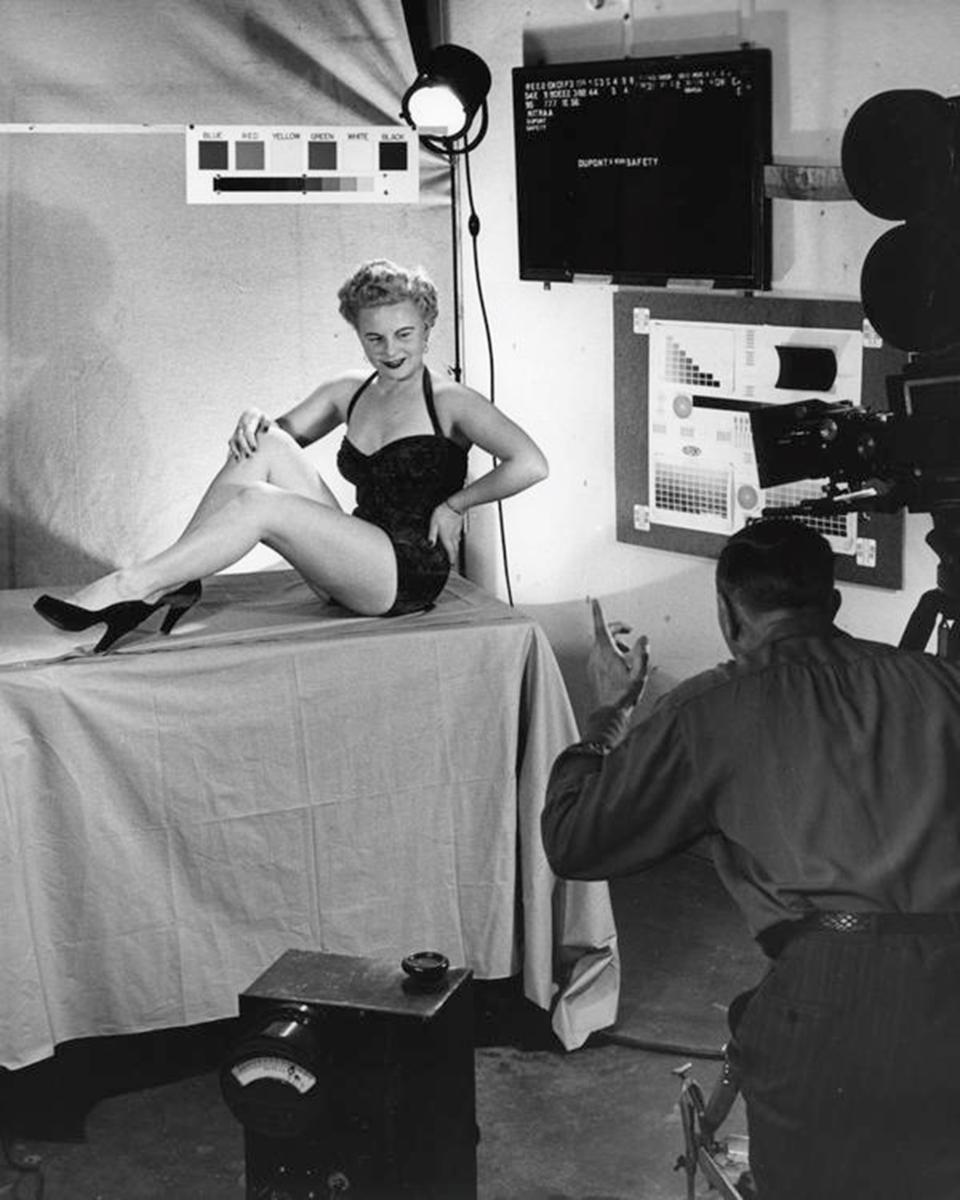

This photograph is part of the DuPont Company Product Information Collection (Accession 1972.341). It was taken in 1955 at the DuPont plant in Parlin, New Jersey when the site was producing cellulose acetate materials, including motion picture film like the one undergoing color testing here. The DuPont-Pathé Film Manufacturing Corporation began in 1924 to manufacture and sell cinema film. Manufacturing at Parlin evolved over the decades as DuPont synthesized various manmade materials. Some of the earliest products were explosives, followed by other commodities such as pyroxylin automotive paints and coatings as well as adhesives like Duco cement. These products all came from the same raw materials and were based on the nitration of cellulose.

Historians have recently illuminated the problem of inherent bias in color films of the twentieth century, focusing on film's inability to reliably capture the variable shades and textures of darker skin. Part of this bias began in the manufacturing labs where experiments in color calibration took place. A standard image of a White woman named Shirley was used for calibration in Kodak photography printing labs for many years to confirm that machinery was in working order and processing chemicals were fresh. Unfortunately, the long history of bias for lighter skin tones was built into the sensitivity and color balance of these photographic materials, due in large part to a lack of diverse representation among Kodak product development employees.

Like Kodak, the DuPont model was a light-skinned woman, photographed above wearing a bathing suit and high heels with a man who is directing her while operating a movie camera. The data board on the wall indicates that this is a test of “safety film,” a non-flammable cellulose acetate formulation that had supplanted the flammable cellulose nitrate film by 1950. Fires involving cellulose nitrate were extremely hazardous due to the release of oxygen during the burning process, and movie film projection was especially risky due to the use of hot illuminating bulbs

This image is jarring today. The attire of the model is unnecessarily skimpy, even if the goal was to evaluate skin tone. Although the DuPont Company had a significant number of female employees at the time, the expectations and depictions of women were of the typical objectifying sort, common to the mid-twentieth century.

The bathing suit itself was probably one of the resilient and elastic fabrics produced by DuPont. Orlon, Lycra, rayon, and nylon were all marketed at some point for swim attire. Of course, bathing beauties have long been used for marketing products including cars, radios, and beauty, so why not show off a DuPont product? Still, it seems extraordinarily exploitative to use female employees as bathing suit models in a publication distributed company-wide; a 1955 issue of Du Pont’s Better Living Magazine even featured nylon halter style suits and other summer styles, modeled by female employees of the Martinsville Virginia Nylon plant. It is curious how the models posing in Better Living were chosen. Did they volunteer, were they nominated by colleagues, or were they approached directly? Imagine how awkward it would be to have your boss suggest you model swimwear for a publication viewed by your co-workers!

The bathing suit itself was probably one of the resilient and elastic fabrics produced by DuPont. Orlon, Lycra, rayon, and nylon were all marketed at some point for swim attire. Of course, bathing beauties have long been used for marketing products including cars, radios, and beauty, so why not show off a DuPont product? Still, it seems extraordinarily exploitative to use female employees as bathing suit models in a publication distributed company-wide; a 1955 issue of Du Pont’s Better Living Magazine even featured nylon halter style suits and other summer styles, modeled by female employees of the Martinsville Virginia Nylon plant. It is curious how the models posing in Better Living were chosen. Did they volunteer, were they nominated by colleagues, or were they approached directly? Imagine how awkward it would be to have your boss suggest you model swimwear for a publication viewed by your co-workers!

In 2010, the DuPont Parlin plant published a pamphlet touting their long history of contributions to the local economy. The images and text within depicted a much different company from that seen above. They highlight a diverse workforce, demonstrating internal advancements in company policy for both women and people of color.

When compared to the earlier examples of the proliferation of racial bias and sexist stereotypes in the mid-twentieth century, this pamphlet reveals how far corporate America has come and underscores where societal improvements are still to be made.

Laura Wahl is the Library Conservator at Hagley Museum and Library.

Laura Wahl is the Library Conservator at Hagley Museum and Library