I doubt you would be shocked if I told you that there is a lot of erroneous information out there! As well intentioned as they may be, some folks are inclined to repeat such false information, at least until another well-intentioned person stops to dig a bit deeper. As summer travel season creeps up on us, I am inspired to tackle one particular case—a “suit-case” if you will—over how and why it took so long for wheeled luggage to become commonplace here in America.

Conventional wisdom holds that no one thought to put wheels on luggage until the early 1970s. People are keen to point out that we went to the moon before a patent was issued for a wheeled suitcase. This is simply not true. Ever since the invention of the wheel thousands of years ago, we have been using them to move heavy and awkward things around. The issue was never about the idea of attaching wheels to luggage, but whether people thought it was necessary.

In the nineteenth century, inventors put wheels on all kinds of things—storage and display shelves, furniture, and even trunks. Based upon patents alone, inventors explored the possibility of attaching wheels to heavy travelling and storage trunks during the first half of the century. Meanwhile, other inventors explored the option of making the luggage itself a wheel. Between 1868 and 1895, multiple patents were granted for cylindrical luggage with metal hoops designed to be rolled to its destination. Here is a model of such a trunk in Hagley’s patent model collection:

The inventor, Louis Ransom, earned multiple patents for trunks and trunk hardware despite the fact that he was never in the trunk-making business. He was an artist, most well-known for his painting of abolitionist John Brown as he made his final walk to the gallows. A Currier and Ives lithograph of Ransom's painting, courtesy of the Library of Congress, is depicted to the right. P.T. Barnum exhibited this painting at his museum in New York City during the summer of 1863. Ransom’s depiction of Brown looking compassionately on a Black mother nursing her child—which was most likely fictional— was so controversial that some historians believe it helped stoke the devastating New York City draft riots.

The inventor, Louis Ransom, earned multiple patents for trunks and trunk hardware despite the fact that he was never in the trunk-making business. He was an artist, most well-known for his painting of abolitionist John Brown as he made his final walk to the gallows. A Currier and Ives lithograph of Ransom's painting, courtesy of the Library of Congress, is depicted to the right. P.T. Barnum exhibited this painting at his museum in New York City during the summer of 1863. Ransom’s depiction of Brown looking compassionately on a Black mother nursing her child—which was most likely fictional— was so controversial that some historians believe it helped stoke the devastating New York City draft riots.

It seems that the cylindrical travelling trunk never caught on with consumers. I failed to locate any advertisements in newspapers or directories or existing trunks in the antiquing world. That did not quash the potential of adding wheels to luggage—especially as air travel grew in popularity.

By the mid-twentieth century, air travel became economically accessible to most Americans. Unlike steamships or railroads, airplanes had weight restrictions. The old steamship trunks of yore would be too heavy and bulky for the airlines to accommodate. This is when the modern handled suitcase came into common usage. But as air travel grew, so did the size of airports. Soon, travelers found themselves carrying large, heavy bags ever-longer distances. A few patents were issued for wheeled suitcases and bags. Several patents were issued for separate carts that could be attached to suitcases. But travelers seemed determined to carry their own bags and few of those inventions were ever manufactured or sold.

The first that truly sparked widespread interest was patented by Bernard Sadow in 1972. Sadow worked for a luggage company. As the story goes, he was in an airport in Aruba struggling to carry his family’s suitcases when he spotted a piece of heavy equipment being rolled around the airport on a wheeled pallet. He turned to his wife and declared, “I know what luggage needs. Wheels!”. After his trip, he removed some casters from the bottom of a piece of furniture, attached them to the suitcase along with a leather strap and merrily wheeled his invention around the house.

But his invention had limitations. The suitcase was top-heavy and difficult to turn. Further, the wheels were small and did not swivel like modern casters. Besides, who needed a wheeled suitcase when there were professional porters to handle bags, luggage carts at airports, and it was considered manly to carry one’s own suitcases? America simply was not ready to whole-heartedly embrace the invention.

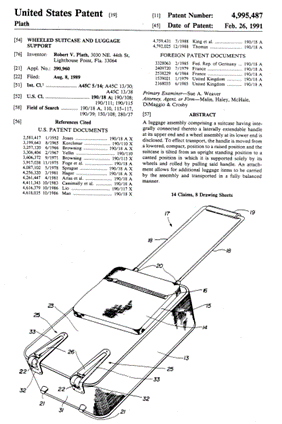

By the 1970s, a few notions of societal “baggage” were tossed aside and encouraged travelers to adopted wheeled luggage. First, it became acceptable for women to travel alone. Manufacturers found a new market as wheeled luggage was easier for women to handle by themselves. Second, an airline pilot named Robert Plath not only patented a far superior design for rolling luggage, he made it manly and cool! He moved the wheels to the short side of the suitcase and added a telescoping handle (Wheeled Suitcase and Luggage Support, Patent #4,995,487, Robert V. Plath, Lighthouse Point, FL, February 26, 1991). This carry-on bag became very popular with flight crews. It didn’t take long after dashing, uniformed pilots and attractive flight attendants were seen effortlessly wheeling their bags through airports before civilian air travelers wanted one of those bags for themselves. Called the “Rollaboard” suitcase and manufactured by Plath’s company, Travelpro, it became the standard for carry-on luggage. It was so popular that onboard aircraft storage bins were designed specifically with its dimensions and features in mind.

By the 1970s, a few notions of societal “baggage” were tossed aside and encouraged travelers to adopted wheeled luggage. First, it became acceptable for women to travel alone. Manufacturers found a new market as wheeled luggage was easier for women to handle by themselves. Second, an airline pilot named Robert Plath not only patented a far superior design for rolling luggage, he made it manly and cool! He moved the wheels to the short side of the suitcase and added a telescoping handle (Wheeled Suitcase and Luggage Support, Patent #4,995,487, Robert V. Plath, Lighthouse Point, FL, February 26, 1991). This carry-on bag became very popular with flight crews. It didn’t take long after dashing, uniformed pilots and attractive flight attendants were seen effortlessly wheeling their bags through airports before civilian air travelers wanted one of those bags for themselves. Called the “Rollaboard” suitcase and manufactured by Plath’s company, Travelpro, it became the standard for carry-on luggage. It was so popular that onboard aircraft storage bins were designed specifically with its dimensions and features in mind.

Today’s carry-on bags are even more lightweight than the Rollaboard and boast four spinning casters. But the intention remains the same—to invent the easiest, lightest, least expensive method for getting to, from, and through an airport. It took over 100 years and a lot of trial and error for the public to catch on. Who knows what the next big thing in luggage will be? And how long it will take for travelers to adopt it.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library