In World War II, the Sperry Gyroscope Company was engaged in the design and manufacture of crucial machinery and instruments for the United States Navy. Commissioned to document the development of these inventions was the artist Alfred D. Crimi. Sicilian born and American raised, Crimi employed his skills to portray the testing of some of the most advanced equipment of the war. These illustrations were then to be used by Sperry Gyroscope in promotional materials.

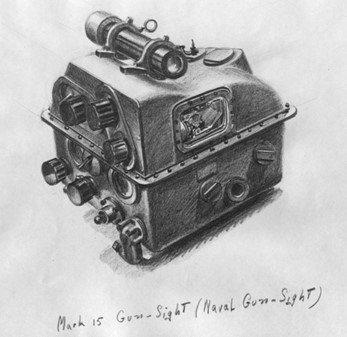

However, these are not simply stiff, technical drawings. Crimi trained in New York and Italy as a fine artist and thus was able to imbue these pencil drawings and ink washes with a more expressive character.  On drawings merely of equipment, like the gunsight above, the tone and linework is rendered in a way that does not suggest hard, cold metal but a more pliable and approachable material.

On drawings merely of equipment, like the gunsight above, the tone and linework is rendered in a way that does not suggest hard, cold metal but a more pliable and approachable material.

Crimi spent much of his time at the Sperry plant in Long Island, New York, studying the technicians and engineers as they worked. His manner of bringing human subjects into his art is excellent. The top image of a gunner poised within the sphere of a gun pod, centered and floating in space like a character from mythology or science fiction, is arresting and communicative. Portraits of the various engineers at work on the machinery are rendered with a beautiful line work that follows the contour of the figure and calls to mind the American Regionalist art of Thomas Hart Benton. Crimi's oil painting of a man at the upper gun turret (bottom) shows only the turret itself and its struts, floating atop a cloud layer. This effect is surrealistic and memorable, but also illustrates the field of vision and the sense of flight one would have while operating the turret. What’s more, Crimi allows us to see through the figure and to discern what his hands are holding at the same time. In several other illustrations, Crimi uses this visual device with great skill, rendering thick metal surfaces transparent in order to demonstrate various procedures. It is both artful and practical for portraying the operation of these machines.

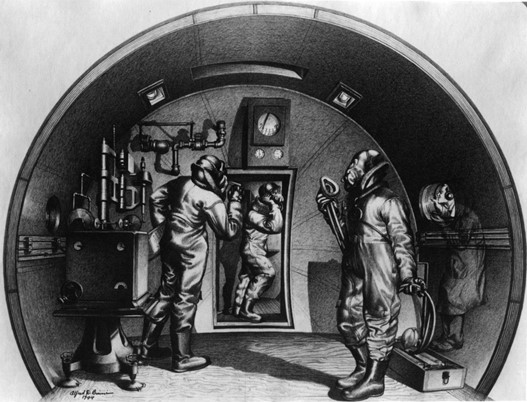

One example of this is in his series showing the altitude chamber, which reproduces the climate and pressure of the altitude at which the bomber plane would be traveling at in order to train airmen and test equipment. These marvelously executed scenes have multiple figures and lots of visual interest. In addition to these fully rendered drawings are a series of gestural sketches Crimi did with ink and brush, showing various technicians and other workers engaged in their jobs or standing by. Of note are some well observed likenesses of the senior engineers.

Crimi also emphasized the combination of man and machine that seemed to be taking place. Gunners appear to merge with their turrets. A portrait of a pilot, covered in air mask and hood, looks heroic against the clouds, but also eerily alien with his pupils doubled by the goggles. For the sake of the war effort men were having to push their own bodies beyond what had been thought possible, and Crimi’s portrayal echoes some of Italy’s own Futurism in that sentiment.

Crimi also emphasized the combination of man and machine that seemed to be taking place. Gunners appear to merge with their turrets. A portrait of a pilot, covered in air mask and hood, looks heroic against the clouds, but also eerily alien with his pupils doubled by the goggles. For the sake of the war effort men were having to push their own bodies beyond what had been thought possible, and Crimi’s portrayal echoes some of Italy’s own Futurism in that sentiment.

These artworks were photographed and reproduced in the late 1940s; the copies are available for viewing in the collection of Sperry Gyroscope Company photographs and films (Accession 1986.273, Box 143). They are amazing examples of an artist going a step beyond a simple documentary job and producing images of wonder and fascination.

Alex Lattanzi is the Collections Assistant at Hagley Museum and Library