Looking through the microscope to visualize the surface of a collection document or photograph is one of the best parts of a conservator’s job. Photographic images in particular often contain fascinating details not immediately apparent until you zoom in. Sometimes this detailed field of view brings out less pleasant aspects of the materials’ life. Small specks, barely noticeable with the naked eye, may be revealed. If these specks are circular, brown, and raised, they are probably the leavings of an insect or spider.

When I first thought about writing on the conservation aspects of insect poop on cultural materials, I considered what other terms could be used to describe such a thing. What more formal or specific words are used in place of poop? "Frass" is typically used to describe loose residues from infestations of insects that have resulted in accumulations of debris. This is common with wool garments or rugs colonized by protein eating beetles or moths and their larvae.

As larvae grow, they cast off their exoskeleton multiple times. Hollow husks, called exuviae, are left along with fecal debris. On a side note, frass is gaining traction as a plant fertilizer, in part because of the chitin content from the exoskeletons. This chitin stimulates plant growth.

Whatever it you call it, bug poop falls under the umbrella of biological contamination; a type of secretion or deposit that includes blood, sweat, and mold. When the contamination is extensive, it can elicit health concerns. Biological materials can harbor hazardous microbes, which in turn can cause damage to paper materials by breaking down the cellulose polymer chain. Fungal contamination brought on by water damage can result in stains of various colors. Bacteria and mold often occur together on contaminated items, making them more difficult to deal with safely.

Materials are not always severely damaged by bug droppings. Photographic prints frequently have a glossy or smooth surface that allows for removal of droppings. Under the microscope, the tip of a fine scalpel blade held at just the right angle can help to pop off the raised residue..

But before you are tempted to grab a blade, be warned that improper technique could result in permanent loss of text or image areas. Old dry specks of insect droppings are unlikely to be harmful to the longevity of archival or personal papers and photographs. Sometimes it is best to leave well enough alone.

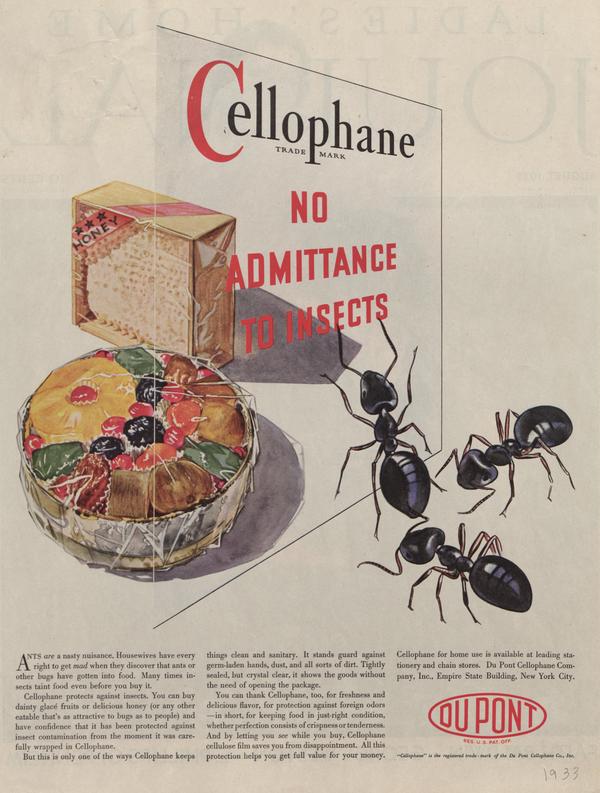

As illustrated by this DuPont Cellophane advertisement, enclosing valued items in a storage container or behind glass is the best way to avoid contamination. Housekeeping is also important for reducing the possibility of damage. Vacuum regularly and clear out spider webs and insect carcasses, which are a source of food for other living bugs. Keeping your home or storage area cool and dry reduces the ability of insects to thrive and reproduce and increases the protection of your historical documents.

One, perhaps unexpected, defecator is the common honeybee. Honeybees do poop, and no, that is not what honey is made from. Rather, they fly away from the hive to “do their business.” Hagley has a few interesting nineteenth and early twentieth-century trade catalogs related to beekeeping. The bee woodcut to the right is from the (profusely) Illustrated Circular and Price List of Sunny Side Apiary, published in 1882 in Baltimore, Maryland.

One, perhaps unexpected, defecator is the common honeybee. Honeybees do poop, and no, that is not what honey is made from. Rather, they fly away from the hive to “do their business.” Hagley has a few interesting nineteenth and early twentieth-century trade catalogs related to beekeeping. The bee woodcut to the right is from the (profusely) Illustrated Circular and Price List of Sunny Side Apiary, published in 1882 in Baltimore, Maryland.

Laura Wahl is the Library Conservator at Hagley Museum and Library