June is National Dairy Month. When I think about dairy, I think about cows. And cows make me think of one of my favorite patent models in Hagley’s collection: John P. Clement’s Cattle Pump.

June is National Dairy Month. When I think about dairy, I think about cows. And cows make me think of one of my favorite patent models in Hagley’s collection: John P. Clement’s Cattle Pump.

Clement’s invention allowed livestock, such as dairy cows, to pump their own water. That may seem kind of silly which begs the question why was this necessary? And, more importantly, HOW did they train a cow to do this?

The “why” is easy when you think about it. When the vast Great Plains of America were opened to settlement, enormous herds of cattle were allowed to graze upon thousands of acres of land. While land and grass for grazing were plentiful, water was not. Most of the water was locked in aquifers, sometimes hundreds of feet underground. There was barely enough surface water to support settlement, let alone agriculture and livestock. Sure, wells were sunk to access the water or windmills were built to pump it to the surface, but how could people get water easily to the livestock without lugging it all over the prairie?

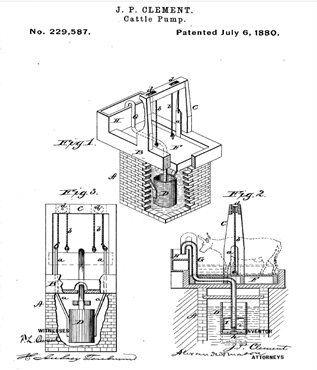

The solution: let the livestock do it themselves! Inventors constructed a semi-raised platform connected to a pumping mechanism sunk in a reservoir or well. Once the animals knew that a tub or trough was the source of their drinking water, they simply ambled up to it. In the process, the platform was pressed downward, operating the pump which added water to the trough. When the animal drank their fill, they stepped off the platform and the pump to reset for the next cow customer.

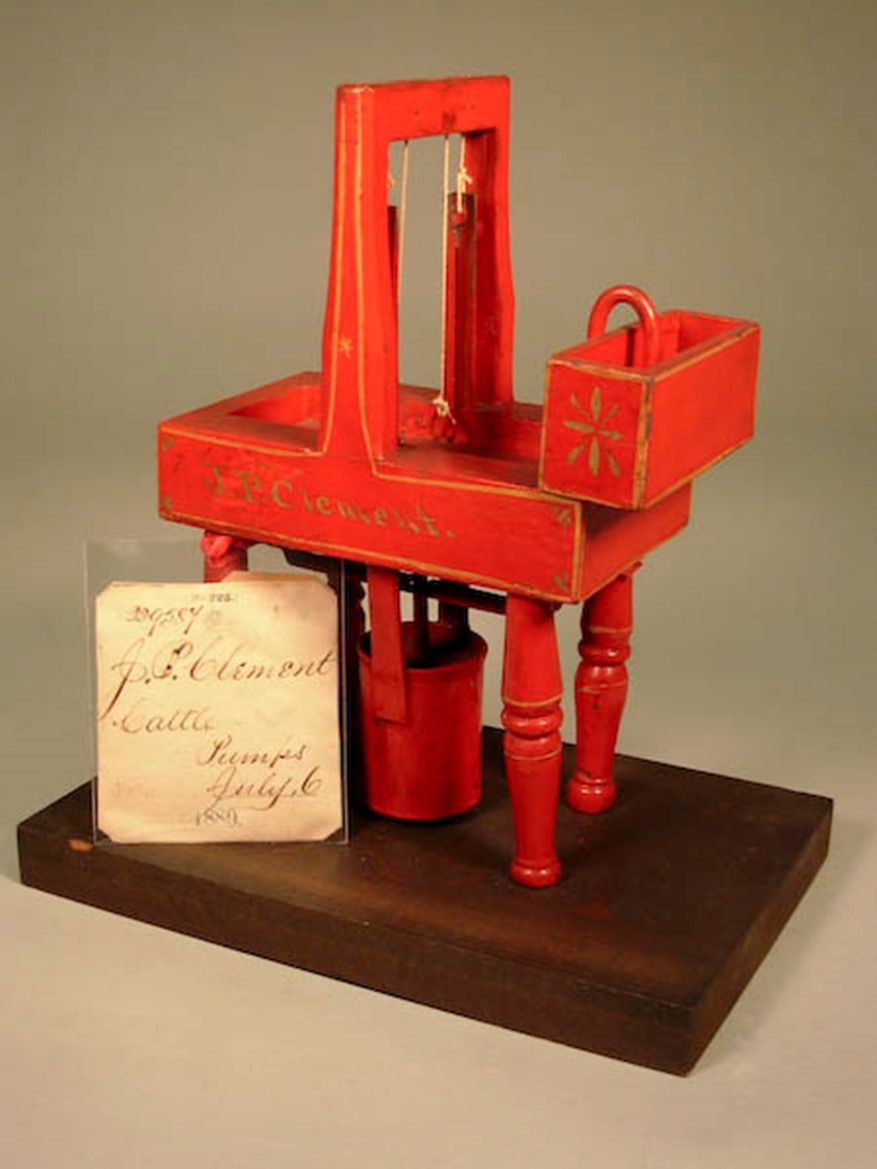

Were these cattle pumps popular? If the number of patents taken out on these devices is any indication, absolutely! Around 50 patents were issued by the end of the nineteenth century. The first was patent number 1,274 issued to Andrew Bailey of Ashtabula, Ohio way back in 1839. This brings us back to the patent issued to John P. Clement in 1880 and its accompanying model in Hagley’s collection.

Clement’s pump was designed to be situated on a platform built above a well. The pump is the tall, red cylindrical object underneath the platform that would be submerged in the well. At the front is a trough fed by a tall arching pipe at the center. When the animal stepped on the platform, it pushed a piston down into the pump forcing water up the pipe and filling the trough. Pulleys with ropes or chains set into the center arch allowed air pressure within the pump to raise the platform back to its original position after the animal drank its fill and left.

Born in New Hampshire in 1824, John Clement moved west to Illinois around 1855 and took up farming. He later married and moved to Grinnell, Iowa. He quit farming due to “bodily infirmities” and went into the insurance business. And he of course tried his hand at inventing, earning this patent as well as one for a windmill in 1870. But these, as well as a few other inventions for which he did not seek a patent, were not successful. When he died in 1882, his obituary lamented that if only Clement “had the education of a machinist, his hand could draft and fashion what his mind devised.”

Tragedy struck his family a mere six weeks after he died. A cyclone destroyed his home killing his two teenage children and seriously injuring his wife. There is no indication that despite his occupation as an insurance agent that they took out a policy on him or their home. As a childless widow in her fifties with her home destroyed and body broken, Mrs. Clement moved in with her brother’s family who lived in the nearby town of Malcom, Iowa.

Sometimes we think of the past as being too far “past” to provide any solutions to our modern problems. But one successful inventor came up with a similar “cow-powered” device at the end of the twentieth century. In 1999, James H. Anderson of Alberta, Canada invented a pump that dispenses water when a lever is nudged by the cow’s nose. Called a Frostfree Nosepump, it works year-round, even during Canada’s frigid winters, and requires no additional power source. Anderson’s company is still in business and thriving.

Sometimes we think of the past as being too far “past” to provide any solutions to our modern problems. But one successful inventor came up with a similar “cow-powered” device at the end of the twentieth century. In 1999, James H. Anderson of Alberta, Canada invented a pump that dispenses water when a lever is nudged by the cow’s nose. Called a Frostfree Nosepump, it works year-round, even during Canada’s frigid winters, and requires no additional power source. Anderson’s company is still in business and thriving.

One satisfied user stated:

“It doesn’t take cattle very long to figure it out. You just fill the pan…When I came back, one cow figured it out and was showing the rest how to do it…They smell the water and know it’s there, and figure it out very quickly.”

Guess you can teach new cows old tricks!

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library