At a recent conference, I attended a session on media identification and basic assessment. While most of this I already knew, it is always great to have a refresher, especially when I come across new media formats in our collections.

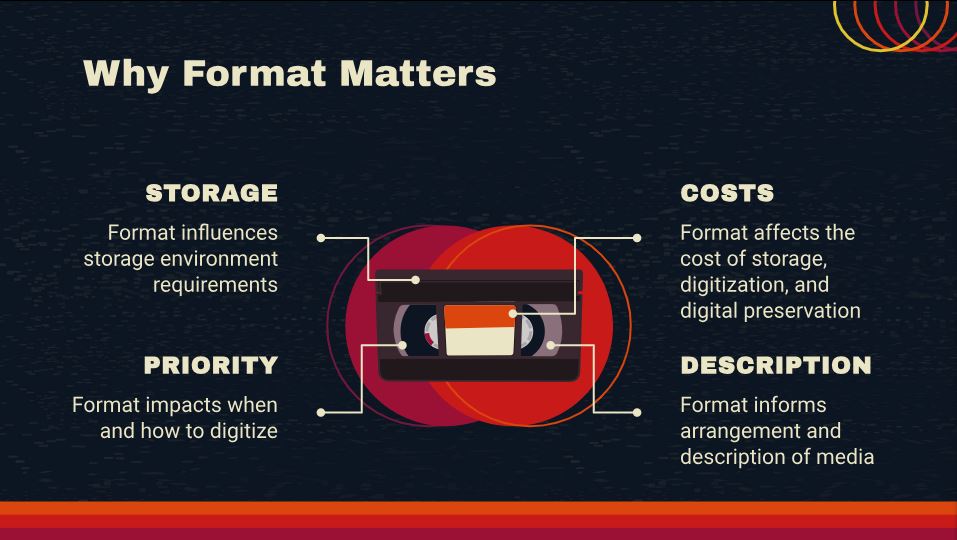

Why is it important to for us identify the type of media? The format impacts the storage, costs, description, and priority for the item. By knowing what we have, we can make informed decisions.

There are four larger categories of audio and moving image formats: film, magnetic media, grooved media, and optical media.

By film, we mean motion pictures. It can include just images or images and sound (you can see the sound waves when included which is quite interesting). There are sprocket holes, which is how the film is advanced, and you can see the images. It is described based on its size (35mm, 16mm, 8mm, or Super 8 being the most common). Film is usually housed in cans on a reel or core, they are stored flat to keep from being damaged. One thing, as archivists, we need to be on the look out for is any degradation of the film. This can be mold, delamination (when the layers separate), warping, shrinkage, color fading, or vinegar syndrome (when the film starts to decay it smells like vinegar is not a good thing). To significantly slow the deterioration of film, it is stored in a freezer. But this also means if we are taking a film out to be digitized, it is a multiple day process because it cannot go straight from freezer to room temperature. It must slowly acclimate the room temperature to prevent damage.

Magnetic media can be video or audio. This is where we get into formats you probably have had: VHS, Beta, U-Matic, reel-to-reel, or compact cassettes, to name a few. You cannot see the data with the naked eye and it requires some sort of playback machine. Magnetic media is stored upright, like books on a shelf, and are kept in the stacks (not the freezer, but on the cooler side). Like film, there are certain signs of damage we need to look for: mold, sticky shed syndrome (sticking to itself or leaving a gummy residue during playback), warping, shrinkage, etc. There is also a ticking timeline archivists are up against with magnetic media. They were predicted to last about 20-30 years before degrading and becoming unusable. We are well past this “deadline” for many of the items.

Grooved media includes cylinders, discs, and belts. There is a physical groove cut on the item and it is played back using a needle. Think vinyl records (although they can also be made from aluminum, lacquer, or shellac), phonograph cylinders (which could be wax or plastic), to Dictabelts. Like magnetic media, grooved media is stored upright and kept in our normal stacks. They are stored in their own boxes to prevent damage, but do not require special storage conditions.

The last major category is optical media: laser discs, compact discs, and DVDs. This is probably the category most people are familiar with today. They can contain video, sound, or data. Like magnetic and grooved media, there is no special storage conditions required, although we generally separate discs into their own box. But this is more for ease of storage than a particular need. Part of my responsibilities is to pull the contents off the discs so it can be accessed without needing the disc in the future (which, like magnetic media, has a “lifetime” we are quickly surpassing). I have written more about what that process looks like here.

This is just a quick look at audio and moving image media. The panel was a great refresher and emphasized the importance of proper identification of media so that we can properly store and describe it.

Ashley Williams Clawson is the Processing and Digital Archivist at Hagley Museum and Library