Although it is estimated that over 15,000 books have been written about Abraham Lincoln, there always is another angle or lens through which we can view his life. Many of us are familiar with his role as president of the United States during the Civil War, his efforts to end slavery, his stirring speeches like the Gettysburg Address, and his tragic assassination. But before all that, he was a simple, self-taught country lawyer on the western frontier. Or, at least, that is the picture our schoolbooks paint of him. Like most paintings, the big picture is clear enough, but the details are a bit fuzzy when you zoom in.

True, he did not attend law school or follow the typical path trod by law students at the time that consisted of “reading” law books with another lawyer. He read law books on his own such as William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. When he felt he understood the law well enough, he took the oral bar exam and passed in 1837. He began practicing with John Todd Stuart—cousin to his future wife, Mary Todd. He eventually founded his own firm with his friend, William Herndon.

His was, as one legal scholar put it, a “volume” business. He charged “modest” fees but took on an aggressive case load. By the time he was elected president in 1861, Lincoln and his partners handled over 5,000 litigation matters including civil, criminal, and constitutional cases in both state and federal courts.

This is where the facts begin to deviate from the “rail-splitting,” “hick country lawyer” persona Lincoln had an active hand in creating. One scholar referred to him as “an incisive, determined, and assertive litigator.” He may have appeared in court in simple, awkward dress and used common frontier language peppered with anecdotes and amusing stories. But that shell concealed a razor-sharp legal mind that had a unique talent for making even the most technical concepts clear to any prairie judge or jury.

His expertise extended to patent matters. Those who knew him recalled his keen mechanical mind. He read books on science and mathematics in his spare time. From the days of his youth, he was fascinated by machinery. Lincoln would crawl under and over machines to learn exactly how they worked. This interest blended with his legal talents on over 20 patent cases, five of which went to trial.

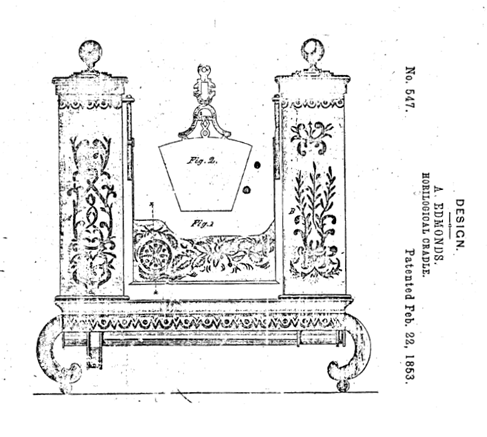

Recently, I was shocked to discover that Hagley owns a model from one of his patent cases. A photo of the model and an image of the patent drawing are below.

This patent was awarded to Alexander Edmunds for an invention he called a “horological cradle.” “Horological” refers to clocks. Before electricity, clocks were driven by a series of weights and pulleys that needed to be wound periodically to keep them running. The inventor’s cradle rocked using a similar mechanism, with the cradle literally serving as the clock’s pendulum, thereby freeing up mother’s hands for other work. Two brothers, George and John Mayers (sometimes spelled “Mayer” or “Myers”), paid Edmunds for the use of the patent.

But the Mayers brothers did not do their homework. The patent was issued not for the cradle or the mechanism, but for the painted decoration on the outside. It was a design patent, not a utility patent. The difference is that a “design patent’ protects the way an article looks—in this case, the pattern of the decoration. While a ‘utility patent’ protects the way an article is used and works.

The patent was practically worthless. Buyers cared about the benefits of a self-rocking cradle, not the fancy paint job. Any manufacturer could drop in clockwork machinery of any design and simply change the decoration on the outside without infringing on the patent. Naturally, they sued. And they won.

The inventor appealed and it eventually wound its way up to the Illinois Supreme Court. Needing an ace trial lawyer well known to the court, the brothers hired Lincoln, certain that their claims would be upheld.

Lincoln put up a strong defense. He even brought in a functioning model of the cradle, wound it up, and let it run while the trial continued…for too long it seems. Judge David Davis reportedly asked when it would stop. Lincoln replied: “It’s like some of the glib talkers you and I know, Judge, it won’t stop until it winds down.”

Despite Lincoln’s efforts, the court saw things in a different way. True, the inventor may have committed fraud by misrepresenting what the patent covered. But there was no proof of the inventor’s intention to do so and the brothers did not read the patent carefully, if at all. Any sensible person would understand that the patent only covered the cradle’s decoration. They cited caveat emptor, or “let the buyer beware,” and the inventor won the case.

Lincoln was hired as local counsel on another important patent trial. This became known as the “Reaper Case” involving Cyrus McCormick’s celebrated harvester in which Lincoln prepared for a “forensic contest” with one the most celebrated trial lawyers of the era, Reverdy Johnson. But that is a story for another day.

That day will be Monday, February 10. I will be giving a talk here at Hagley. I will discuss Lincoln’s patent cases, his status as the only U.S. president to earn a patent, his belief and promotion of the American patent system as an engine that drove the American economy, as well as Lincoln’s connections—humorous and tragic—to other patent models in Hagley’s collection. To register, visit: https://www.hagley.org/calendar/special-tours.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library