This March, the last three living members of the World War II Ghost Army were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal. These service members were part of a vast and largely unknown effort to draw enemy fire toward dummy military installations, thereby protecting the real Allied troops.

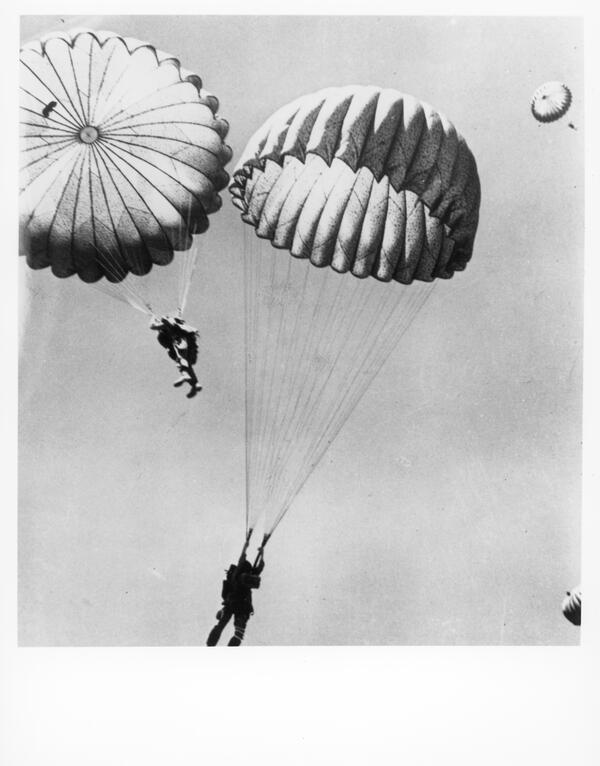

Hagley’s Library collections offer numerous stories of the rise of the military-industrial complex and corporations' wide-ranging material support for the war. The DuPont Company quickly mustered facilities to produce additional chemicals used for explosives, plastics, and nylon (Accession 2004.268). This latter synthetic polymer was used for parachutes and to strengthen tires. Nylon was taken off the civilian market in 1942 to go into war production, and nearly 39 million yards of fiber were used to make 3,860,000 24-foot parachutes like those in the image to the right.

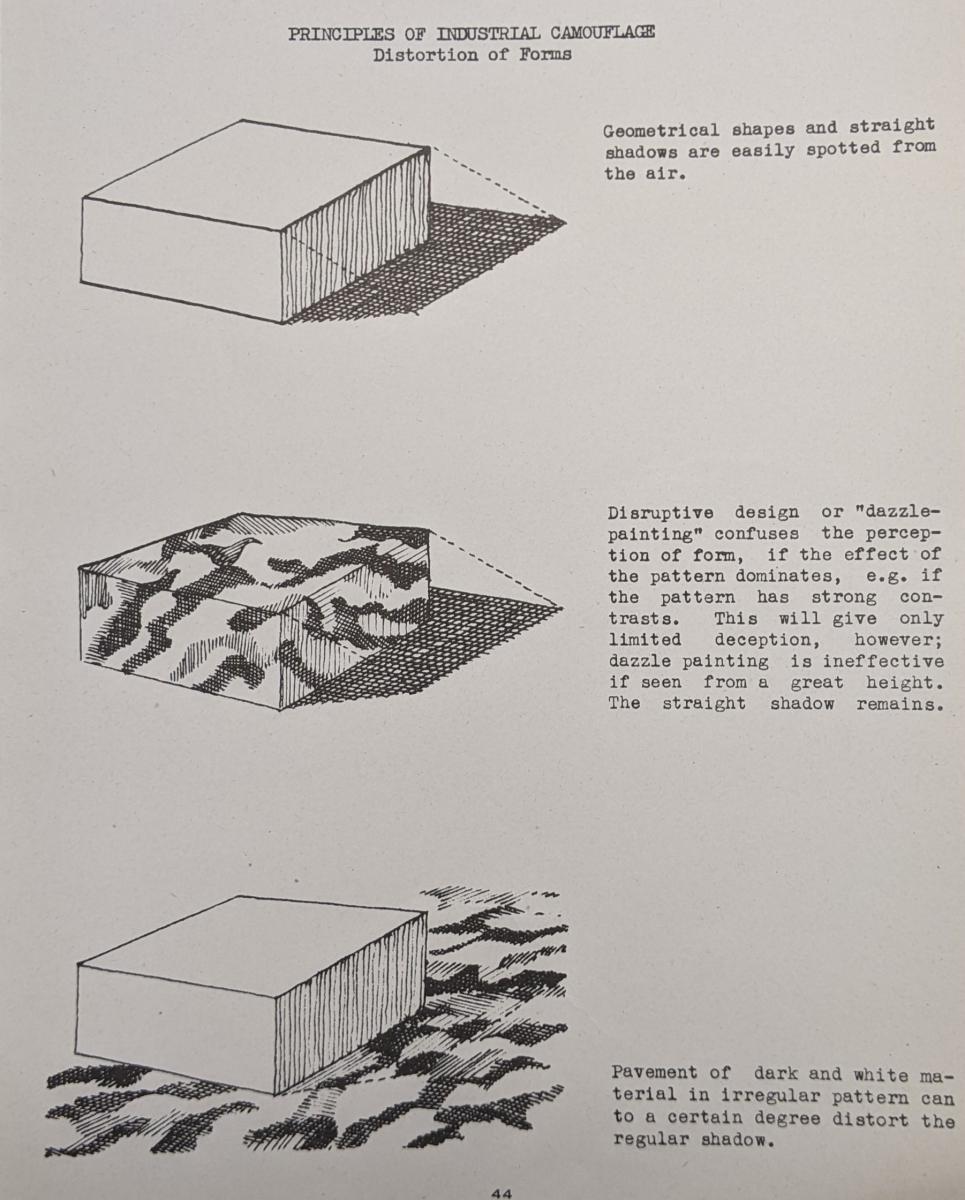

Beyond these records are still more photographs, manuscripts, and books relating artists’ and designers’ contributions to the art of deception. They studied the view of factories and government and civilian buildings from the air, and created fake trees and canopies to avert bombers’ attention. Investigating how concealment coloration works for wild animals, they developed “dazzle” painting, also known as pattern deception.

William Pahlmann, the well-known mid -20th century interior designer, was one artist who learned about camouflage from the Works Progress Administration. The William Pahlmann papers (Accession 2388) include information about his U.S. Army Air Force service and his teaching at the Jefferson Barracks Camouflage School in St. Louis, Missouri and at the Overseas Replacement Depot training camp at Greensboro, North Carolina.

Raymond Loewy, an industrial designer, also contributed significantly to the war effort by creating a $2,000,000 "cloak" for the Glenn L. Martin bomber factory at Baltimore, Maryland. A newspaper clipping in his scrapbook also listed the details of another complex project: “In Seattle, one of Boeing's plants was hidden under a dummy town. The fake 26-acre residential scene was complete with sidewalks and parking strips, shade trees and gardens. Chicken feather trees, canvas buildings, burlap streets and spun-glass dirt were used...” It is uncertain if Loewy was involved at the Boeing plant.

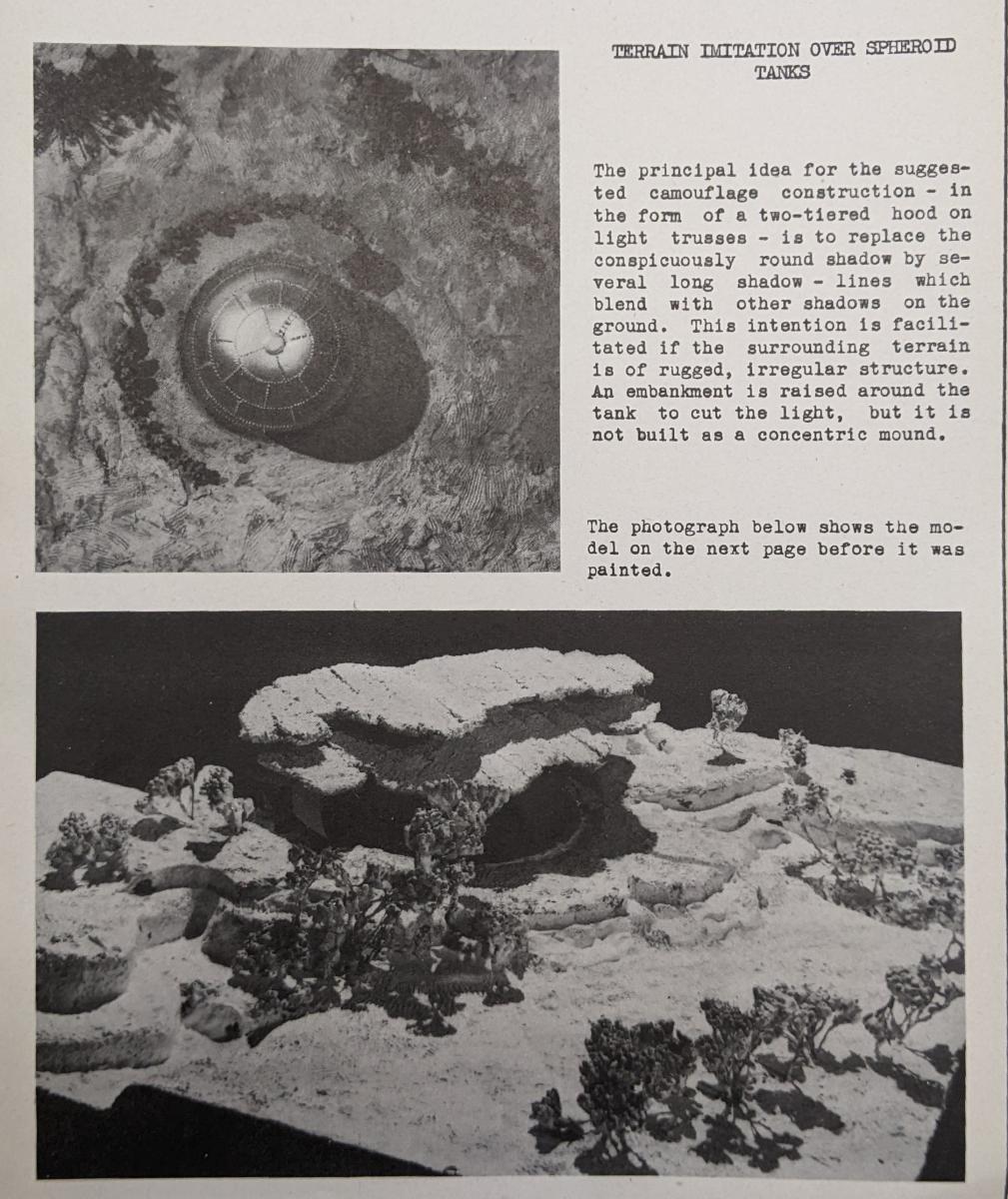

The Pratt Institute School of Design had tasked their students with improving the art and science of camouflage. A handbook, The Industrial Camouflage Manual, was published in 1942 with numerous illustrations to disperse the findings. Notable was the use of aerial photography for visualizing what the aircraft operators and bombardiers would have seen. Trees, real and fake, were indicated as helpful in the landscape for concealment, reducing the need for camouflage on things like tank storage. Irregularities of pattern were studied, such as highways intersecting landscapes, the way shadows were cast from taller buildings, and how a cylindrical tank stood out. Photographs show how 3-D models were used to test various disguising methods.

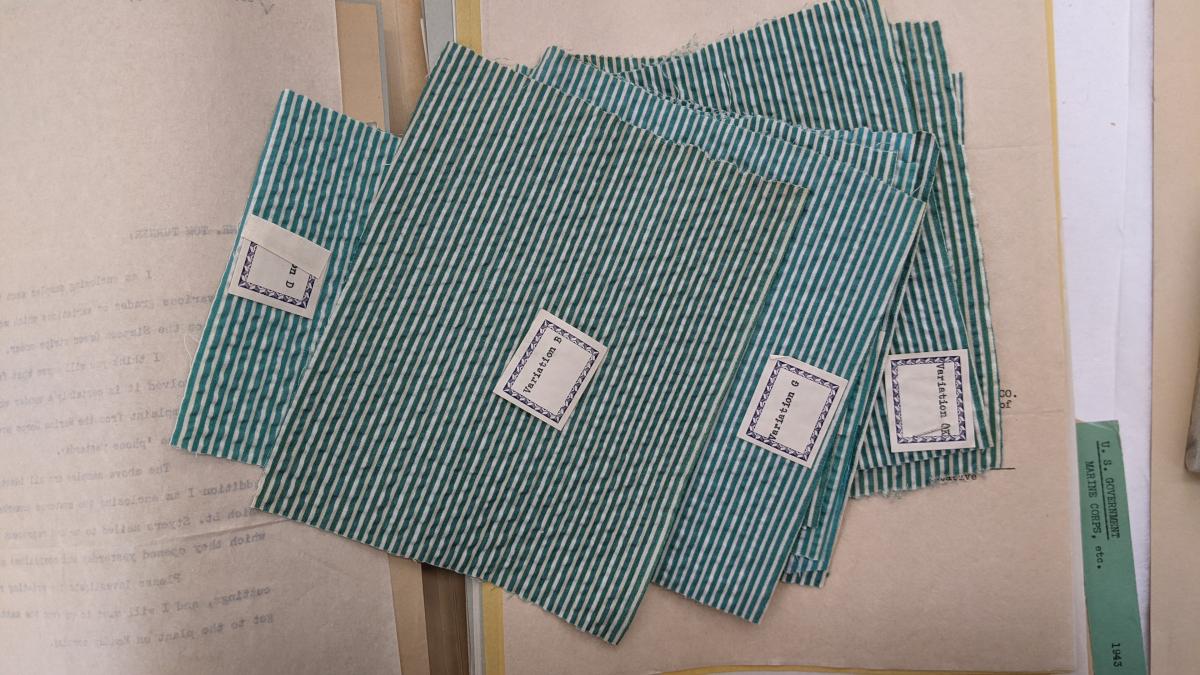

The Joseph Bancroft & Sons records (Accession 0736) of Eddystone Manufacturing are another group of records that contain some information about camouflage materials, specifically the production of textiles.  The Aridye Company was working to complete a bid to dye netting materials for the U.S. military. It was marquisette woven cloth used for mosquito netting. There are some letters indicating that a printed pattern, called leopard spot, was also applied to cloth. The colors were developed to specifications required by the armed forces, including testing for possible skin contact reactions, and bio-deterioration. Copper naphthenate was a significant component for some of the colors. Copper pigments and inks cause deterioration of cloth, so the biocides applied may have had limited impact on the longevity of the netting. The only cloth samples found associated with the project paper records were dark olive netting and finely striped woven fabric similar to seersucker, or possibly mattress ticking (see below and right). The use of this cloth was not immediately apparent in the letters and it lacked the consistency demanded by the military. They had sent back several samples complaining of discrepancies in dye shade and depth.

The Aridye Company was working to complete a bid to dye netting materials for the U.S. military. It was marquisette woven cloth used for mosquito netting. There are some letters indicating that a printed pattern, called leopard spot, was also applied to cloth. The colors were developed to specifications required by the armed forces, including testing for possible skin contact reactions, and bio-deterioration. Copper naphthenate was a significant component for some of the colors. Copper pigments and inks cause deterioration of cloth, so the biocides applied may have had limited impact on the longevity of the netting. The only cloth samples found associated with the project paper records were dark olive netting and finely striped woven fabric similar to seersucker, or possibly mattress ticking (see below and right). The use of this cloth was not immediately apparent in the letters and it lacked the consistency demanded by the military. They had sent back several samples complaining of discrepancies in dye shade and depth.

Civilian Defense Protective Concealment from the Inter-Society Color Council collection (Accession 2188) was a 1942 publication from the War Department. The authors begin with a warning that proper camouflage requires careful planning by trained persons and that “no camouflage at all may be better than camouflage ill-conceived.” Illustrations, photographs, and diagrams propose means of hiding train stations, factories, farms, and other civilian settings by using smoke, earth, mesh, and paint.

I am certain that there are even more stories of camouflage hidden in the stacks and waiting to be exposed!

Laura Wahl is the Library Conservator at Hagley Museum and Library