Thanks to a Hagley Exploratory Research Grant, I was recently able to spend a week at Hagley’s Library to conduct research for my dissertation, which examines the material culture of exploration and field science in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. During my time at Hagley, I focused primarily on the collection of trade catalogues and pamphlets. I’m interested in how the seemingly mundane stuff explorers and scientists carried with them to far-flung places – waterproof clothing, tents, preserved food – changed how these individuals behaved, how they thought about their own bodies, and how they interacted with the environments and local communities they encountered while on their expeditions.

I’m also interested in how the companies that produced these goods appealed to a broader group of consumers by evoking romantic notions of exploration in “exotic” places. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, explorers were big celebrities on both sides of the Atlantic. Some companies took advantage of this, offering free or discounted goods to expeditions with the hope of public endorsement. One such company was the British pharmaceutical manufacturer Burroughs Wellcome & Co., which outfitted many famous explorers with portable medical kits. Their 1934 promotional book, The Romance of Exploration and Emergency First-Aid, From Stanley to Byrd, featured testimonials from grateful explorers who used their products, such as Henry Morton Stanley, who carried multiple Burroughs Wellcome kits on his African voyages. Other travelers chose to thank suppliers in smaller ways. The J. E. Rhoads & Sons, Inc. leather company records include a copy of Richard Byrd’s Into the Home of the Blizzard, published to mark his 1928-1930 Antarctic expedition. Tucked inside is a handwritten note from a J. E. Rhoads employee explaining that Byrd used the company’s tannate shoelaces on this journey and sent the book personally to thank them.

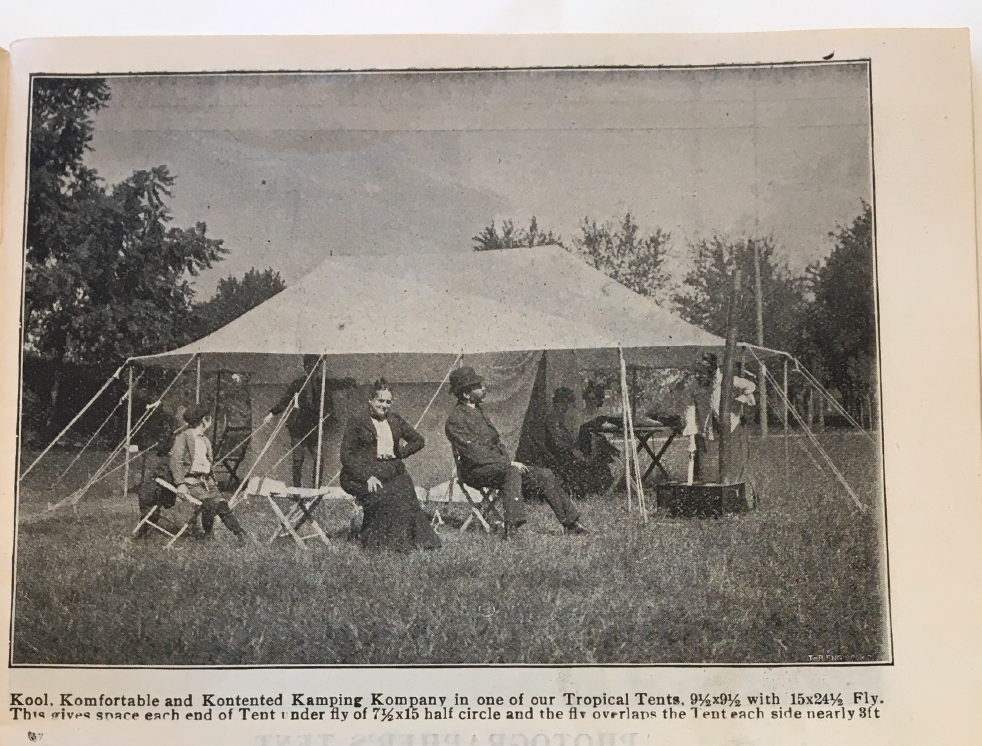

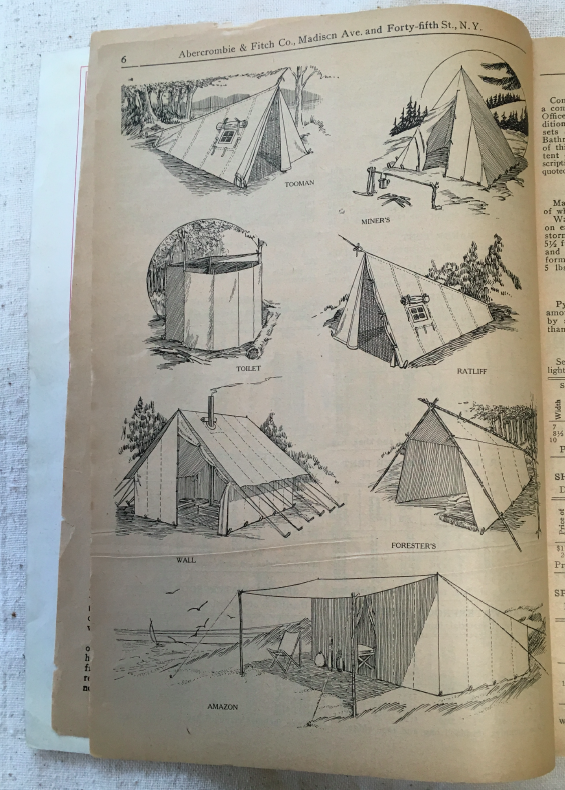

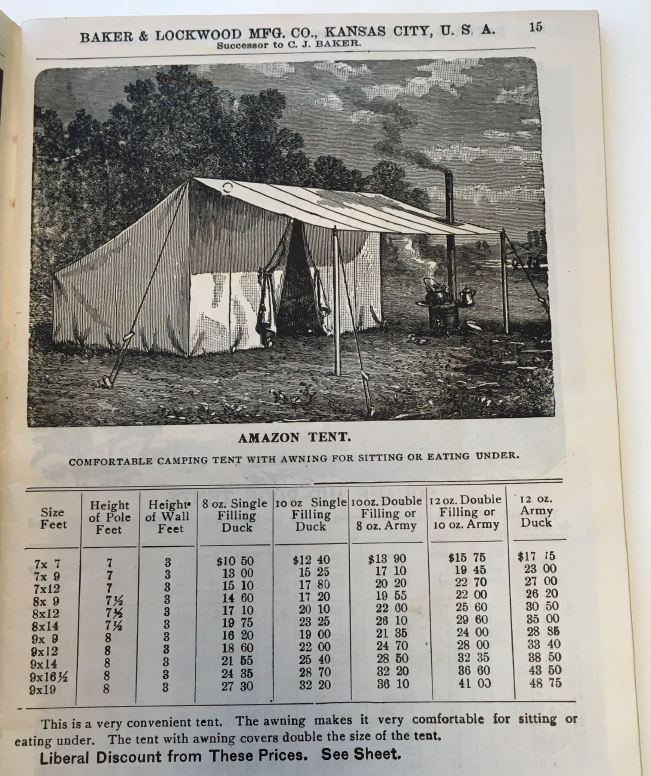

By the turn of the twentieth century, camping and hiking had also become popular activities for many middle-class and affluent Americans. Though most never ventured as far from home as Stanley or Byrd, they could attempt to channel a similar sense of adventure through their consumer choices. Today, Abercrombie & Fitch is known for its casual clothing, but it was founded as an outdoor goods retailer. Abercrombie’s 1923 catalogue boasted that the company’s patrons included “the world’s leading explorers, the foremost members of the flying corps in the armies of Europe and America, and the greatest fishermen and hunters.” Evoking the romance of far-flung travel, the catalogue included items with names like the “Amazon Tent” and “African Tent” (inspired by a design “worked out by the British Army Officers in South Africa to meet the climate conditions”). Abercrombie & Fitch wasn’t the only outdoor outfitter that used this kind of naming to appeal to consumers. For example, customers perusing tents in Baker & Lockwood’s 1903 catalogue could purchase a “Tropical,” “Amazon,” or “Klondike” model. Abercrombie & Fitch did go a step beyond its competitors to sell books by famous adventurers, such as archaeologist Hiram Bingham, naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews, Antarctic explorers Ernest Shackleton and Roald Amundsen, and former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

While I have found many intriguing details in these catalogues, one that I am especially interested in pursuing further is the how these consumer goods may have promoted tacit support for the colonial aspects of exploration. The 1923 Abercrombie & Fitch catalogue (and a similar edition from 1913) proclaimed that while packing for the outdoors could be frustrating, good packing “goes a long way towards accentuating, by contrast…the fierce joy of conquering the wilderness and writing, perhaps, one’s name upon a virgin page.” Exploration during nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was connected to the expanding empires of Europe and the United States. Explorers may have claimed to write their names “upon a virgin page” of the Earth’s surface, but in reality these places often had indigenous inhabitants already. The next phase of my dissertation research will involve teasing out how the rhetoric of “exploration” and “discovery” connected mundane outdoor goods and everyday consumers to colonial conquest throughout the globe.

Sarah M. Pickman is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at Yale University, in the Program in History of Science and Medicine. Her dissertation investigates the material culture of British and American exploration, field science, and travel from c. 1820-1930, with a focus on exploration in extreme environments. She can be found on Twitter at @sarahmpicks