If you listen to news radio on your daily commute or watch the nightly news when you get home, the broadcast will likely include a segment titled something like “Wall Street Report,” summarizing the day’s financial happenings, with data about the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the NASDAQ Composite Index. Though “Wall Street” is a shorthand for the financial sector, for a historian of American cities (and New York in particular) there is some irony in these numbers being lumped together under the banner of “Wall Street.” Although most (but not all) companies that are part of the Dow Jones Industrial Average trade on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), which is on Wall Street, those other numbers you hear about on daily “Wall Street Reports” are for the NASDAQ Composite Index, whose leaders spent significant time and energy to separate their exchange from “Wall Street” physically and in the minds of its users from its inception in 1971 through the 1980s and beyond.

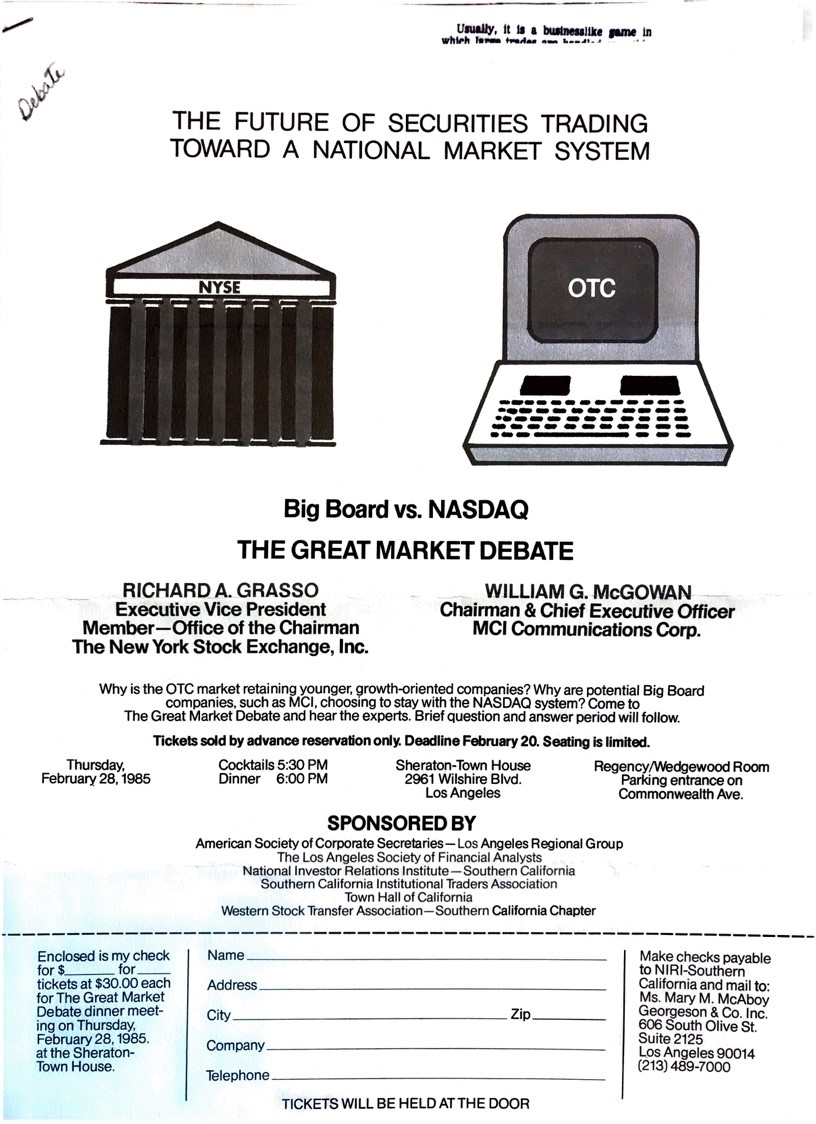

The above document, from the Records of the MCI Communications Corporation located in the Hagley Library collections, illustrates the divergent and conflicting history of these two exchanges. The image is from a published condensation of a debate that took place on February 28, 1985 in Los Angeles between Richard A. Grasso, Executive Vice President of the NYSE, and William McGowan, Chairman and CEO of MCI and member of the Board of Governors of the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD).[1] The debate was over which exchange would be the stock market of the future. By 1984, the NASDQ had moved behind the NYSE as the second largest stock exchange in the country, and it was gaining fast.[2] The NASDQ seemed to have all the momentum. It traded high-tech companies like MCI and Apple and, as the image implies, relied mainly on computers.

In the advertisement, the NYSE is symbolized by a distinctive structure, the neoclassical façade of its headquarters at 11 Wall Street. Inside the building was a trading floor where (at least in 1985) trading in NYSE listed securities took place. The NASDAQ does not have its own office building, nor does it have a physical trading floor. As is alluded to in the image, the NASDAQ (which stands for the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations) allowed for brokers to obtain price information about over-the-counter stocks (those not listed on a traditional exchange) via a computer screen in their home offices. Before the advent of the NASDQ in 1971, one could only gather this information through a series of phone calls. The actual buying and selling of stocks still mostly took place over the phone, though the NASDAQ was moving towards automated trading, as well. Unlike the NYSE, NASDAQ had no grand neoclassical headquarters; its network came together in a server stack at an office park in Trumbull, Connecticut. Gordon Macklin, the first president of NASDAQ, described it as “a computerized trading floor which stretches some 3,000 miles.”[3] In contrast, Big Board stocks, as NYSE stocks are called, were still bought and sold at trading posts on the physical trading floor of the NYSE.

In the 1985 Town Hall debate, McGowan argued that “NYSE resembles the horse-drawn carriages that we occasionally see weaving their way through midtown traffic. That system may be nostalgic but it is completely out of step with the times. Computers coupled with telecommunications that instantaneously transport information, the desire of people to choose their own lifestyles, and the sophistication of the investing public all demand a system for trading like the NASDAQ.”[4]

Yet the papers of MCI in the Hagley Archives reveal a more complex story, one that contains a mix of grand proclamations about the future and the quotidian realities of physically building communications networks. They demonstrate the diverse ways that brick and mortar urban infrastructure shaped high-tech entities like MCI and NASDAQ. NASDAQ’s computerized network still relied on phone lines, computerized regional concentrators in major cities, its main Connecticut server stack, and eventually, a backup server stack in Rockville, Maryland. While MCI was central to the NASDAQ’s high-tech image, MCI was also engaged in the mundane, low-tech work of laying cable on top of railway rights-of-way, tunneling through Manhattan streets, and utilizing infrastructure originally created by Western Union decades before in order to build its microwave and fiber optic communications network. In the coming decades, these fiber optic networks would transform not only communications, but the nature of finance itself. In the cases of NASDAQ and MCI, urban (and inter-urban) infrastructure shaped the form of late 20th-century communications and the evolution of “Wall Street” – just not actually on Wall Street.

[1] “The Big Board vs. NASD: The Great Market Debate,” Town Hall Journal Vol. 47 No. 13 March 26, 1985, MCI Series II Box 85

[2] Robert A. Mamis, Taking Stock Inc. June 1984, MCI Series II Box 85

[3] Proceedings of the 1983 Conference of NASDAQ Companies, MCI Series II Box 69

[4] “The Big Board vs. NASD: The Great Market Debate”

Aaron Shkuda is project manager of the Princeton-Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism, & the Humanities at Princeton University. To support his use of Hagley Library collections, Dr. Shkuda received an Exploratory research grant from the Center for the History of Business, Technology, & Society.