When Hagley Library opened its doors to researchers in 1961, most of our business-related collections held records and images produced and used by White executive-class men in corporate America. Given that American business leadership and Hagley's institutional leadership (not to mention our researchers) were dominated by this demographic at the time, the collection scope and contents are unsurprising. However, the enterprise and innovation landscape was never the Great (White) Man monolith our collections seemingly represented, and over the past 30 years, Hagley has worked to expand our collecting focus in terms of industry type and demographic. This includes making it easier to find and identify women in our archive.

Many of the women in our collections worked for a living. Their reasons no doubt varied over time and place, based on age and race, wants and needs. No matter the reason, they entered the workforce and are immortalized at Hagley. Keep scrolling to see the faces of the working women in Hagley’s archives and learn how to find even more.

In 1919, this photograph (right) was taken depicting the Lester Public School teachers in Lester, PA. None of the women have been identified by the photographer nor by researchers or staff. Still, we know these women would have taught the children of the Westinghouse Steam Division's South Philadelphia Works employees which is likely why this image is included in one of Hagley's Westinghouse collections. The image below is from the same collection and shows an unidentified Westinghouse Steam Division street sweeper at work in South Philadelphia in 1919. Like the women above, the name of this young woman is not known to Hagley staff. Early twentieth-century employees, particularly women of color, were poorly documented by employers, often only appearing in payroll records if ever. The collection this woman's image is a part of includes a list of South Philadelphia Works employees. Perhaps she and the other women can be found there.

While we may be able to name the Westinghouse women—or at least narrow down their identities—based on supplemental materials in our collections, there are many women about whom no additional information is available.

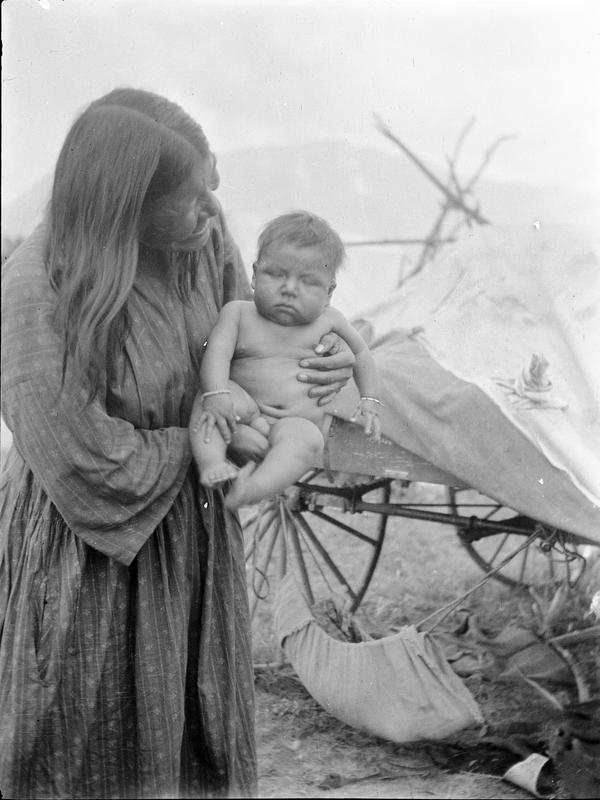

This photograph (right) is of an unidentified Indigenous American woman posing with her child. Her name is not included on the picture, nor is much other potentially identifying information, and it is unlikely she was paid for the use of her image. The photographer was Frank Schoonover, whose collection of photographic negatives resides at Hagley. Schoonover was a magazine illustrator, and part of his practice was to travel around the United States taking pictures for inspiration. Based on the other photos in this image's series, the woman may be a member of a Great Plains tribe since other people captured in the photos are wearing traditional clothing and inhabiting tipi-like structures. That said, White photographers of Schoonover's era were known to stage Indigenous Americans in stereotyped Plains styles, removing the nuance of different tribal identities and practices. The people photographed were also not the final models Schoonover went on to use; those were White women dressed in pseudo-Plains clothing and whose names are identified in Schoonover's notes.

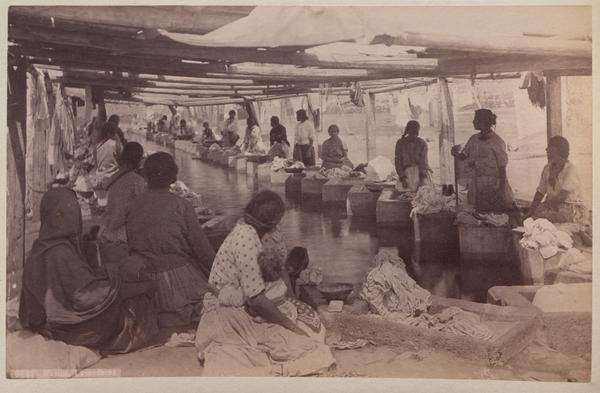

Another image whose subjects suffer the same lack of known identity as the woman to the right is that of the lavanderas (laundresses) seen below at work in Mexico City, Mexico. This photograph was likely taken by William Henry Jackson (1843-1942), an American landscape photographer hired by the U.S. government to amass images of places and peoples worldwide. He did not collect the names of the women he captured here; their identities remain a mystery. The image itself, however, was distributed as part of collectible photograph compilations and is now housed in many American cultural heritage institutions, ironically making the unidentified women well-known yet anonymous.

The women's images in Hagley's collections often served specific purposes. Thus far, we've seen the teachers and the street sweeper whose photos served as operations documentation; the mother and child who likely inspired early twentieth-century mass-produced American art; and the lavanderas whose image was itself mass-produced American art.

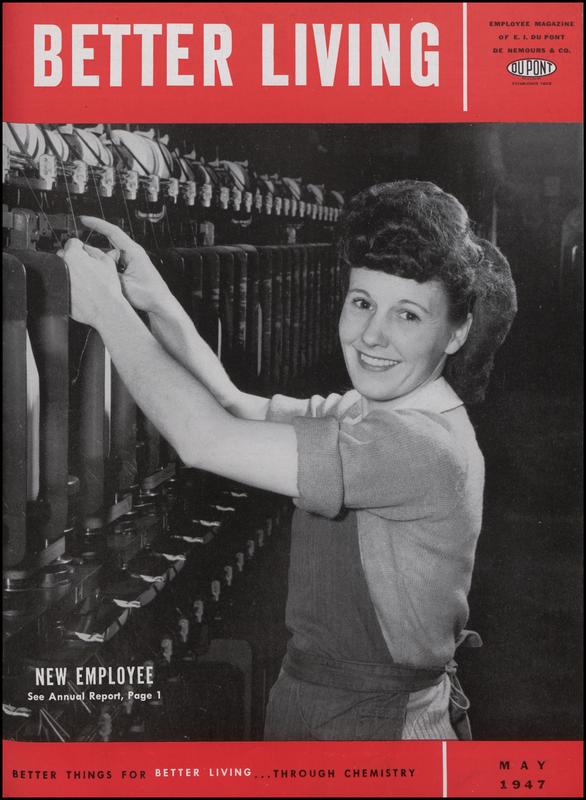

DuPont nylon factory employee Pearl Elizabeth Blair's photo (right) was used on the May 1947 cover of Better Living, the DuPont magazine published as a public relations tool. Women employees and consumers were often featured on the magazine's cover, demonstrating to postwar readers the relative diversity of DuPont's staff and product types. These women were identified in short biographies on the inside cover. One of the few identified women laborers in our archive, Blair started in manufacturing during World War II and continued afterward, joining DuPont in 1946.

Although not identified like Blair, the women in the image below are also in manufacturing, just on the management side. These women supervised lingerie production operations, and their photograph is included in the special bulletin, "Negro Women Workers in 1960." This U.S. Women's Bureau publication includes statistics, analysis, and case studies about Black American women and their employment conditions and contributions. Much of the study compares the experiences of "nonwhite" women to those of the White women surveyed in a study a couple of years prior. While the bulletin uses "nonwhite" as a synonym for Black Americans, this study likely included responses from, and perhaps even photographs of, women who considered themselves of another race or ethnicity outside Black or White. What is clear is that the study attempts to present visual representations of a wide range of professional-class careers. Black women worked as nurses, data analysts, city planners, and musicians. Statistics about working-class Black women are included, but none of these women appear in the bulletin photos, indicating the authors' socioeconomic preferences.

The histories of working women that researchers can explore at Hagley are varied, but we still have work to do. We’re committed to expanding the diversity of our collections’ origins and of whose histories—or rather, whose HER-stories—they can tell. And our commitment does not apply just to the histories of White women, of managerial and upper-class women in business and innovation, but to all women of all races, identities, and abilities.

Hagley staff are also working to make our collections as accessible as possible for researchers through subject headings, digitization, and finding aid (archival inventory) creation. Below is a selection of each that focuses on or includes sections about women’s history:

- Women

- Women in STEM

- Women in the arts

- Women in the marketing industry

- Women in the service industry

- Women in the trades

- Women inventors

- Women—Employment

- Women-owned business enterprises

Digital Projects

- The Extraordinary Life of Rosetta Henderson

- Black Powder, White Lace: A Primary Source Compendium

- Brandywine Valley Oral History Project

Finding Aids & Collections

- Catalyst Inc. (Acc. 2728 and 2021-222)

- Lois K. Herr (Acc. 2462 and 2019-230)

- Elva M. Chandler papers (Acc. 2057)

- Avon Products Inc. (Acc. 1997-209)

- Clarita V. Stubenbord design portfolio (Acc. 2499)

- Beech-Nut Packing Company photographs (Acc. 2022-210)

- Pennsylvania Railroad women workers' oral histories (Acc. 1998-234)

Reference Guide

Women's History: A Guide to Sources at Hagley Museum and Library by Lynn Ann Catanese

These are not comprehensive lists; we’re always adding to our collections. Visit us onsite to explore our collections further, or ask our reference team for help by submitting a question to Ask Hagley at askhagley@hagley.org.

In honor of working women wherever and whenever, Happy Women’s History Month!

Hannah Spring Pfeifer is the Library Coordinator at Hagley Museum and Library.