As my colleague Dan Michelson points out in his earlier post, “Who Was David Sarnoff? Part II: 1930-1971,” beginning in 1924, Sarnoff entered the U.S. Army Signal Corps Reserve and was later called up for active duty during the Second World War. Dan points out that Sarnoff served overseas during 1944 where he oversaw communications leading up to the invasion of France and was later responsible for reestablishing communication links between London and Paris. As significant as these activities were, they don’t tell the whole story of Sarnoff’s wartime service. Discoveries I have made in the audiovisual portion of the David Sarnoff Library collection, including an oral history interview and a small set of photographs, help give us a better understanding of the valuable work Sarnoff performed for the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

David Sarnoff receives his commission as Lt. Colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, Officer’s Reserve Corps, 1924.

The oral history interview is of Hunton Downs, a Signal Corps officer who served on David Sarnoff’s staff for the later portion of Sarnoff’s nine months of active duty. According to Downs, the time he spent with Sarnoff was in Italy, North Africa, and the Middle East, where they travelled far and wide by Jeep, searching for radio transmitters and other communications equipment that could be used for the Allied war effort. As Downs relates, the radio network was vital for a variety of uses, including the distribution of propaganda and other information into Germany and enemy occupied territory. Another mission was to provide radio beacons to friendly aircraft that were participating in a novel “shuttle bombing” campaign that had planes taking off from bases in the UK or Italy and landing at airfields in the USSR. Finally, the US Army Signal Corps provided vital communications links along the “Persian Corridor” that funneled Lend-Lease material from the United States and Great Britain to the USSR by way of Iran and Soviet Azerbaijan.

David Sarnoff in the field with unknown officers.

In the photo above, we see Sarnoff, a Colonel at the time, with two other Signal Corps officers taking a break next to their Jeeps. It’s tempting to think that one of these other men is Downs, but their identities are unknown. This photograph, and several others, appears to match the events described by Downs and seem to show Sarnoff and his staff as they search for radio transmitters. Visible in some of the other photos are abandoned German artillery guns alongside the road they travelled and a village that has been badly damaged.

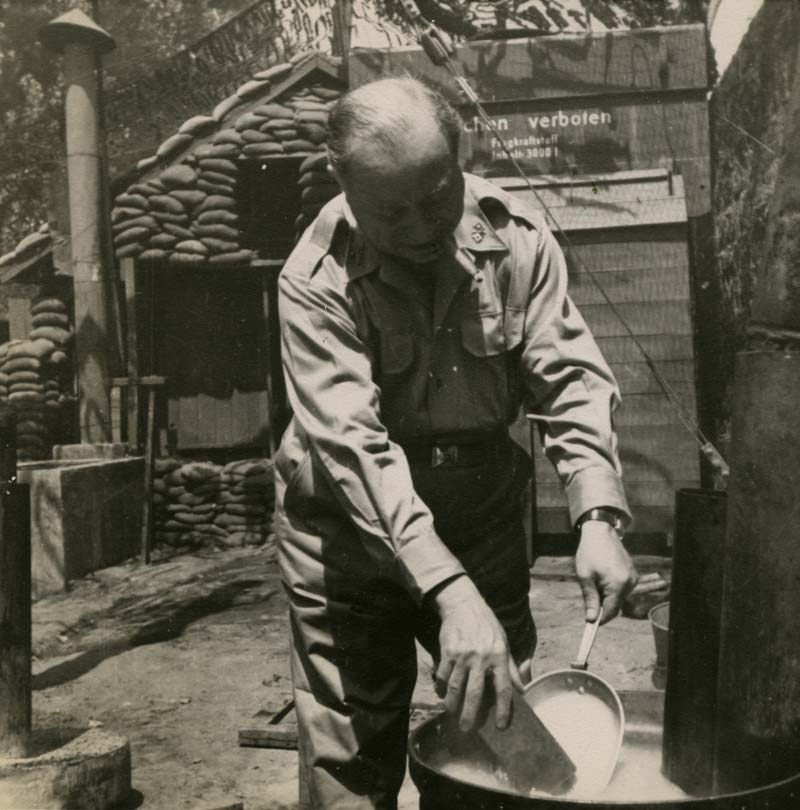

David Sarnoff washing dishes.

Travelling as far and wide as Sarnoff is said to have done, living conditions must have varied considerably. In the photograph above, we can see the future general, washing a skillet in an improvised wash basin. In the background, we see a sandbag reinforced structure and a sign written in German. According to Downs, at other times he and Sarnoff enjoyed more comfortable accommodations, such when they were assigned a luxurious villa overlooking Naples as their residence. However, the comfort of their stay was rudely ended one night when German bombers attacked the city and a bomb hit the home in which they were sleeping. Sarnoff was unhurt, but Downs was injured in the explosion that destroyed part of the house.

Understanding the many ways that David Sarnoff contributed to the success of the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War II, as well as the risks he took and distance travelled in just nine months of active duty, should help us to better appreciate why he was promoted to Brigadier General on December 6th, 1944.

David Sarnoff receiving his promotion to Brigadier General, December 6, 1944.

Kenneth Cleary is the Sarnoff Project Archivist in the Audiovisual and Digital Initiatives Department.