What might your receipt from the grocery store say about your food preferences? A list of processed food might signal a desire or need for convenience. A list without meat or dairy could suggest an ethically-rooted diet. Food variety may speak to the technological and political circumstances of our time: with access to foods no longer confined to seasons or geography [1].

Such food politics are not confined to the human sphere. What animals eat is also defined by technological advancements, transnational policies, convenience, and ethics. My dissertation traces some of these decisions made by scientists, policymakers, feed companies, and farmers through the development of America’s animal feed industry from 1900 to today, particularly for the food of food animals like cattle. Feed receipts are important sources of historical evidence that help me piece together when farms integrated different feed products, revealing these preferences and various political dimensions from different farmers’ perspectives. As a recipient of a Hagley Exploratory Research Grant in 2017, I took the time to look at such farm records.

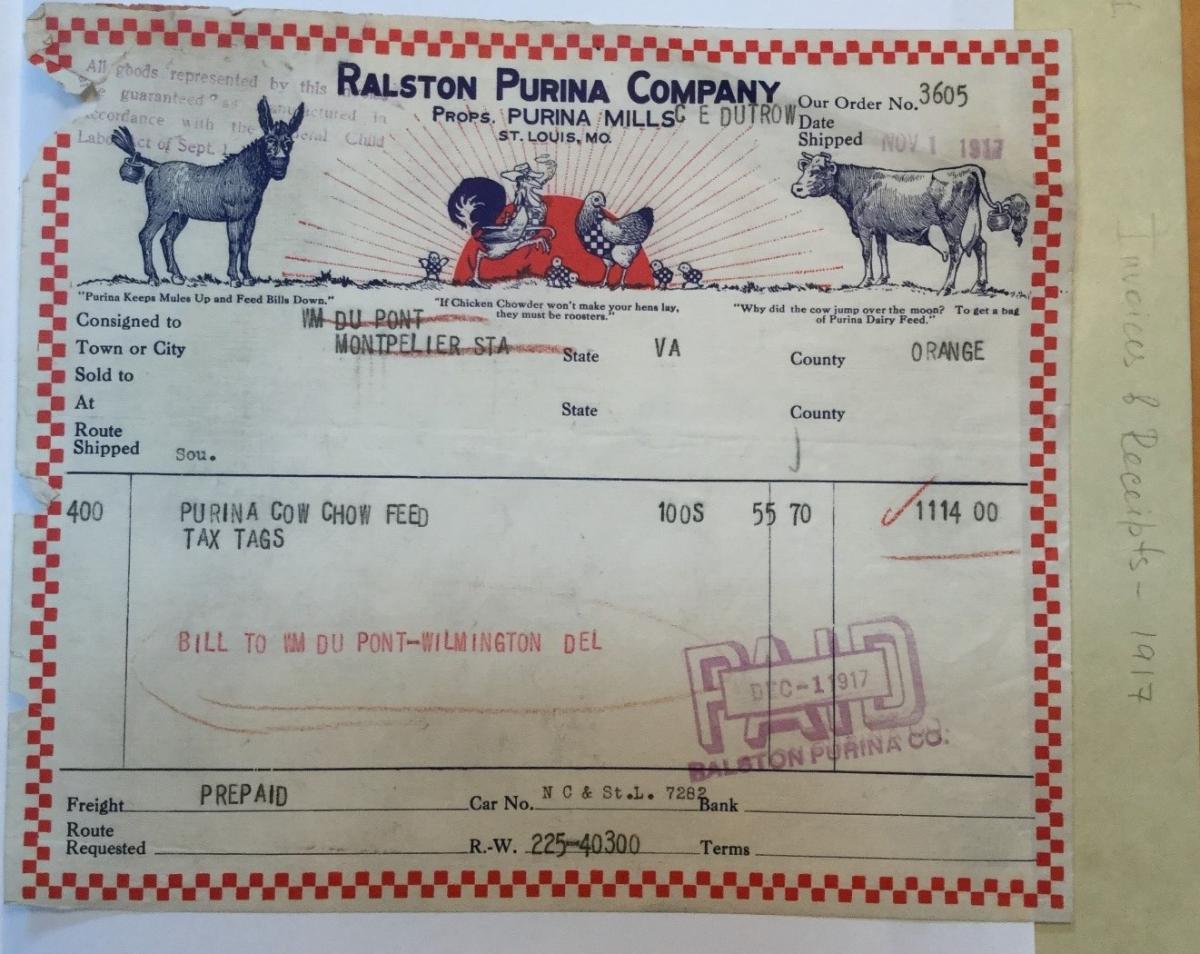

Luckily for me, both William du Pont (1855–1928) and William du Pont, Jr. (1896–1965) kept hundreds of receipts pertaining to their respective cattle and horse farms. Through these sources, I was able to trace not only the development of the du Ponts’ agricultural operations, but the maintenance and expansion of various animal feed companies – including Purina Mills – over the first half of the 20th century.

In my search for specifically mid-20th century feed receipts, the Foxcatcher Livestock Company Papers did not disappoint. Throughout the 1950's, William du Pont, Jr. experimented with different livestock feeds. He tried a specialty sweet mixing feed, invested in the latest “batch feed mixing” technology, and bought raw ingredients and hay from various companies across the country. The records support du Pont Jr.’s case that his farm was intended to be much more than a “hobby” operation, which was contested in federal court by the IRS when he claimed a loss on his taxes in 1960 [2].

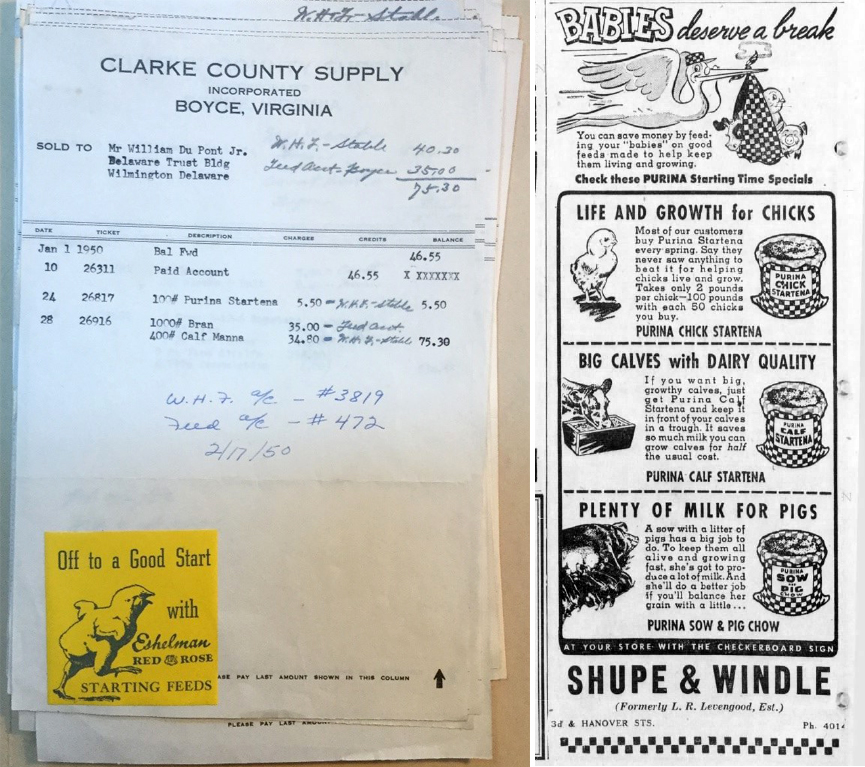

Much of my time at the archives was spent trying to decipher and unpack receipts like this one (above) from Clarke County Supply to Walnut Hall Farm. For example, it’s likely the 100-pound bag of Purina Startena was intended for calves, but the listing is unclear given “Startena” was made for “babies” across species – as illustrated in the above 1950 advertisement from a Pennsylvania newspaper. “Calf Manna” referenced the then Carnation Calf Manna brand; this brand advertised as a multi-species animal feed – for cows, goats, horses, and pigs. With dual purpose feeding in mind, the brand listed was likely fed to both du Pont, Jr.’s horses and cattle.

Additionally, stickers like the yellow chick on this receipt were used throughout the 20th century to advertise new feeds sold by a given supply company. Both the William du Pont and William du Pont, Jr. Collections carry receipts that range in sizes, colors, and images based on the advertising model of a given period and company. But this little piece of evidence from Clarke County Supply exhibits the versatility of this supplier, and the variety of products du Pont, Jr. had at his disposal from this location just down the road from Walnut Hall Farm. The farm animals of du Pont ate feeds coming from everywhere between Washington state (Carnation) and Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (Eshelman Feeds).

Sources

[1] See, for example, Susanne Friedberg. Fresh: A Perishable History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

[2] See also Donald Barlett and James Steele. America: Who Really Pays the Taxes? New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. pp. 217-218

Nicole Welk-Joerger is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Pennsylvania's History and Sociology of Science Program. Her current research focuses on human-animal relations in food production.