On a wet September day in 1963, Sun Oil President Robert Dunlop visited the site of Sun’s new synthetic oil project in the boreal forests of northeastern Alberta. To avoid getting stuck in the muskeg the group needed a tank-like vehicle to access the site, anticipating some of the sticky problems the oil industry would face in the Athabasca region.

In the second half the 20th century, the oil industry turned to new energy sources in remote locations that were expensive and difficult to produce. One new source was bitumen—vast deposits of sand packed with tar-like hydrocarbons that underlie the boreal forests of northeastern Alberta, Canada.

The oil industry long knew the great size of the deposit—over 170 billion recoverable barrels of bitumen. However, the cost, effort, and technology required to make synthetic oil from bitumen hindered commercial development until the 1960s, when Sun Oil made a large investment in Great Canadian Oil Sands Limited (GCOS) and built the first commercial plant.

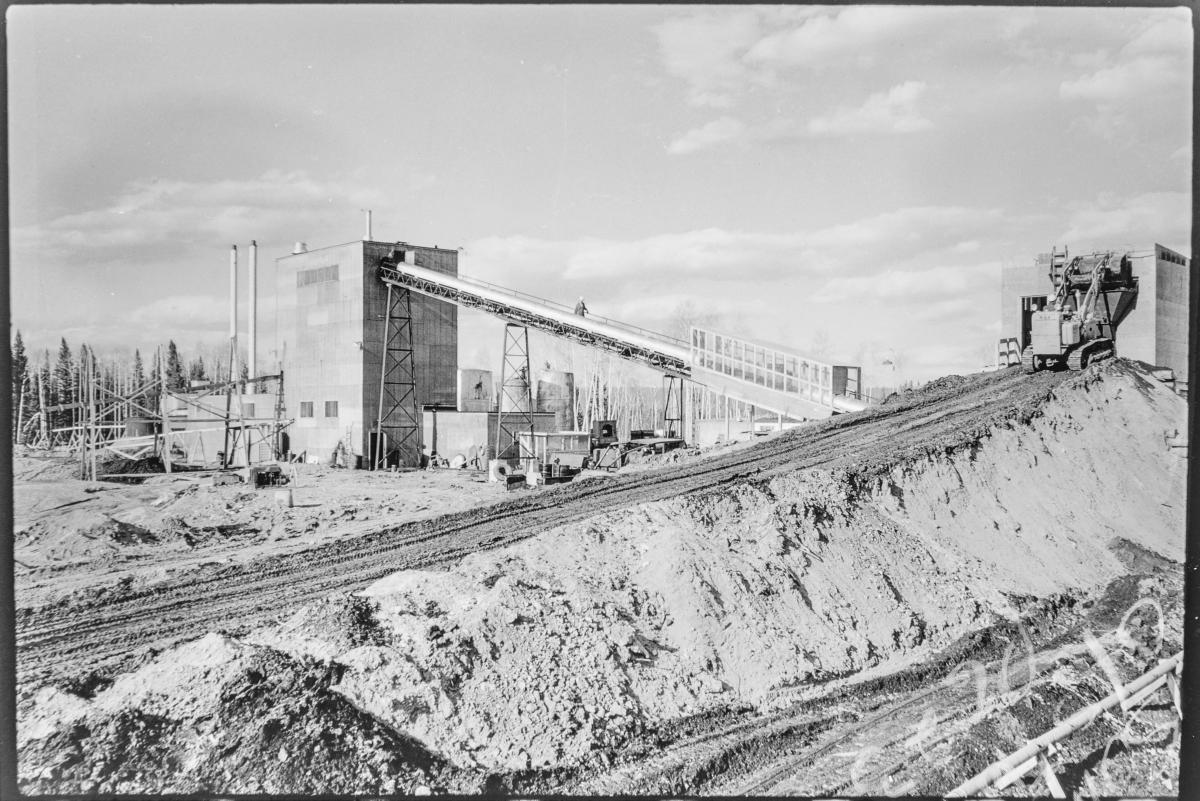

Sun could not pump bitumen like conventional oil. It had to bulldoze all the trees and wetlands that overlay the deposit, then use huge machines to strip-mine the bituminous sand. It then had to boil the material to separate the bitumen from the sand, before upgrading the bitumen into synthetic crude oil.

My PhD research looks at the environmental history of the Athabasca oil sands industry. I am interested in why and how oil companies and governments built unconventional oil projects and how these projects changed the places and people where they were built.

I visited the Hagley Archives to view the Sun Oil collection, which provides a unique company perspective on the development of the oil sands industry that contrasts the government records housed in Canadian archives.

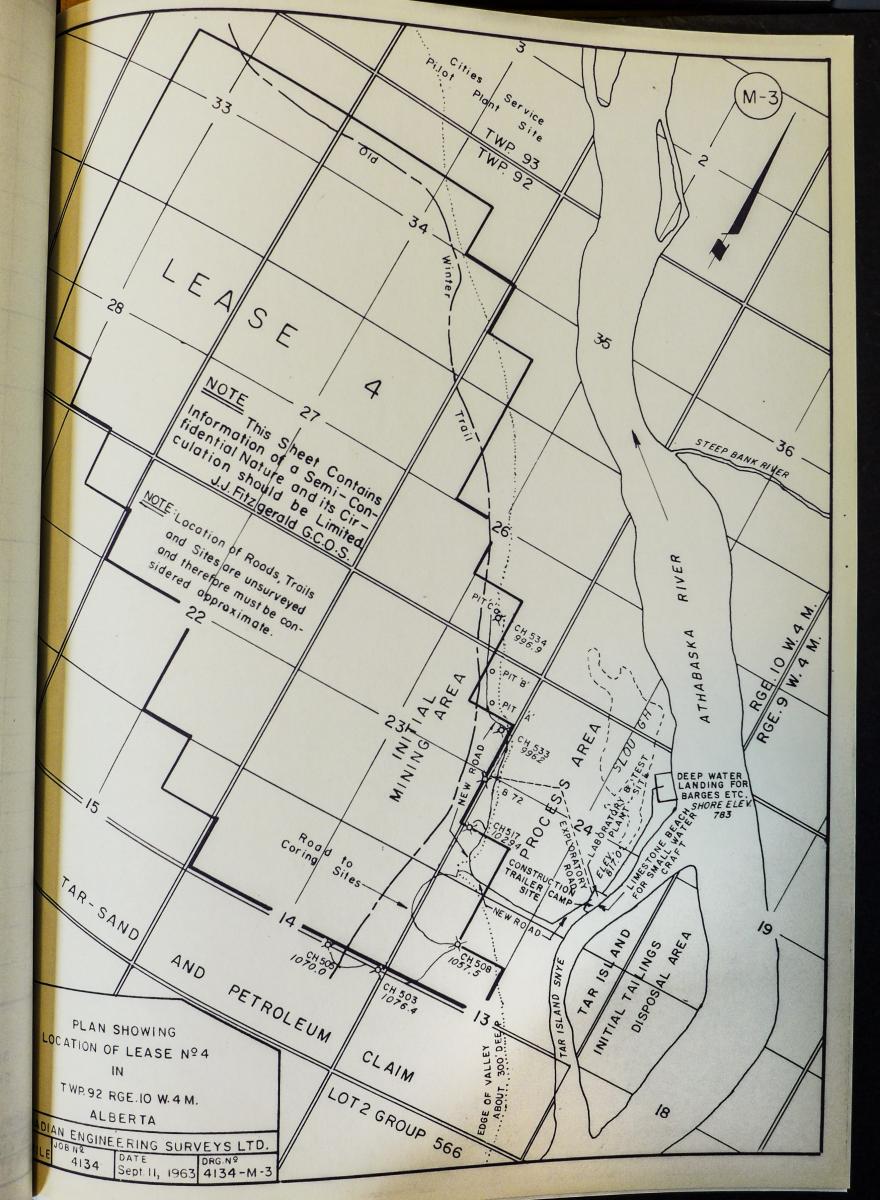

One interesting document I found at Hagley is a 1963 report by GCOS consultant Joseph Fitzgerald of a tour by Sun management. The report describes difficulties of opening of Lease 4, the location of the GCOS plant site.

Lease 4 was remote—330 miles by rail and barge north of Edmonton, Canada’s most northern major city. When Sun built GCOS, it had to build mostly from scratch all of the roads, bridges, buildings, generators, and housing necessary to access and develop the project.

Fitzgerald described how the GCOS team brought a tractor north from Mildred Lake in May of 1963. The team drove into the lease area on an abandoned winter road, which had been cut by a drilling crew in 1949. Fitzgerald’s team fought for two months to push roads through the swampy forests across the lease, following ridges of high ground to reach the river. The crew cut down trees and drained wetlands to make space for buildings, drilling platforms, and machinery.[1] In July, Sun’s J. Howard Pew and Sun’s directors flew up from Philadelphia to tour the site and the company broke ground on the construction of the pilot plant.

After several years of construction, Sun completed the full scale Great Canadian Oil Sands plant in 1967, marking the commercialization of the oil sands industry. The plant immediately suffered from failing boilers, extraction equipment, and electricity generators. It was plagued by fires, floods, and ice. By the 1970s, Sun kept the project going only because the cost of shutting it down would exceed the cost of keeping it running. [2] [3]

The Athabasca region now produces over 2.5 million barrels per day of synthetic oil and bitumen, much of which flows south among the 4 million barrels of oil per day the United States imports from Canada, its biggest source of imported oil. Yet the Sun Oil records at Hagley show that this was never an inevitable outcome.

[1] J. Joseph Fitzgerald, “Sunoco Party # 2 Visit to Fort McMurray - Lease 4 - September 19, 1963,” Accession 1317, Vol. 1, Series 6, Box 35, Folder 1, Hagley Archives.

[2] “The Dawn of a New Age of Energy: Special GCOS Issue,” Our Sun: Magazine of Sun Oil Company, Autumn, 1967, Acc. 1317, Volume 1, Series 6, Box 34, Hagley Archives.

[3] Graham D. Taylor, "Sun Oil Company and Great Canadian Oil Sands Ltd.: The Financing and Management of a "Pioneer" Enterprise, 1962-1974," Journal of Canadian Studies 20, no. 3 (1985), p. 113.

Hereward Longley, PhD Candidate, Environmental History, University of Alberta

@herewardl

www.herewardlongley.com