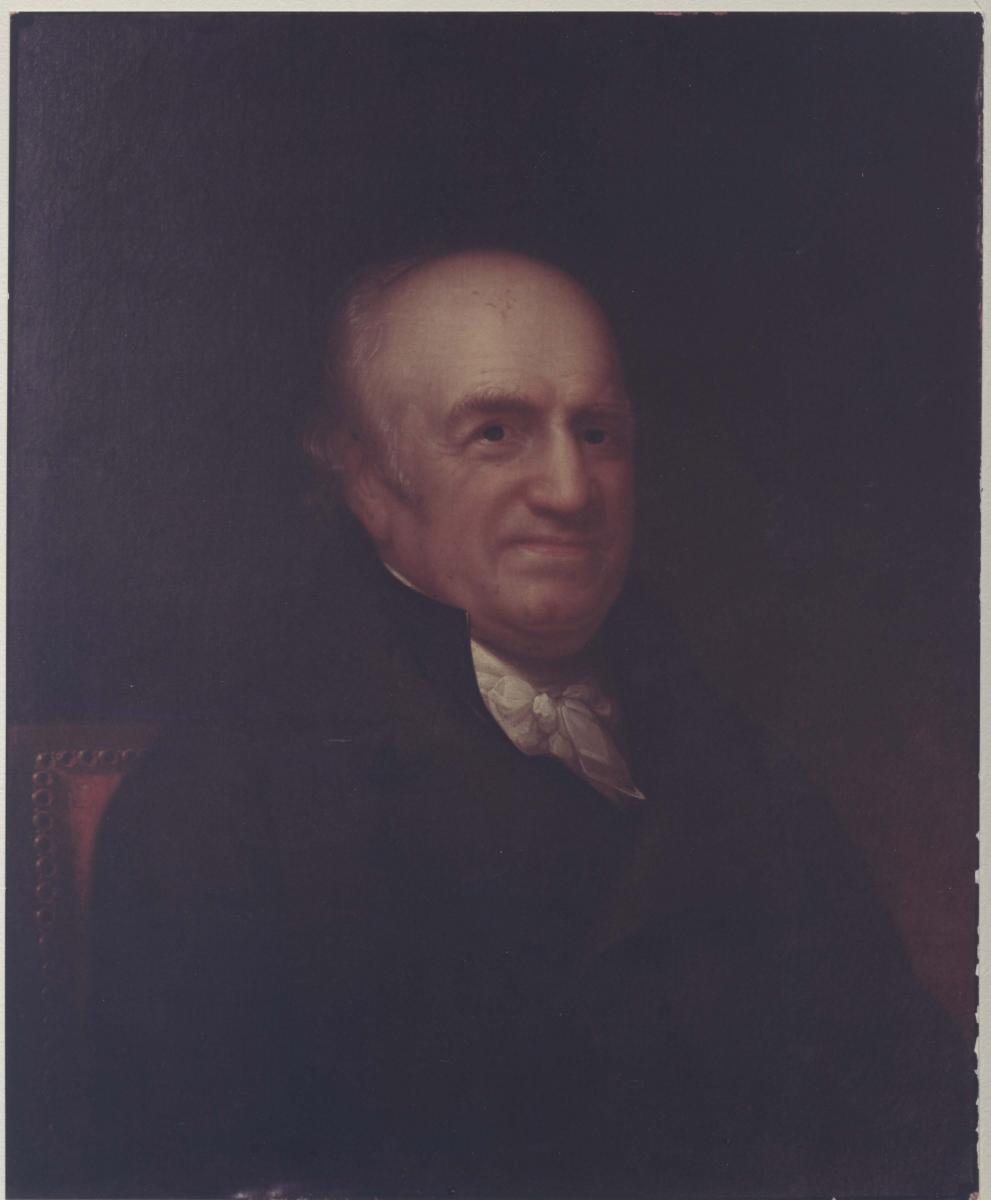

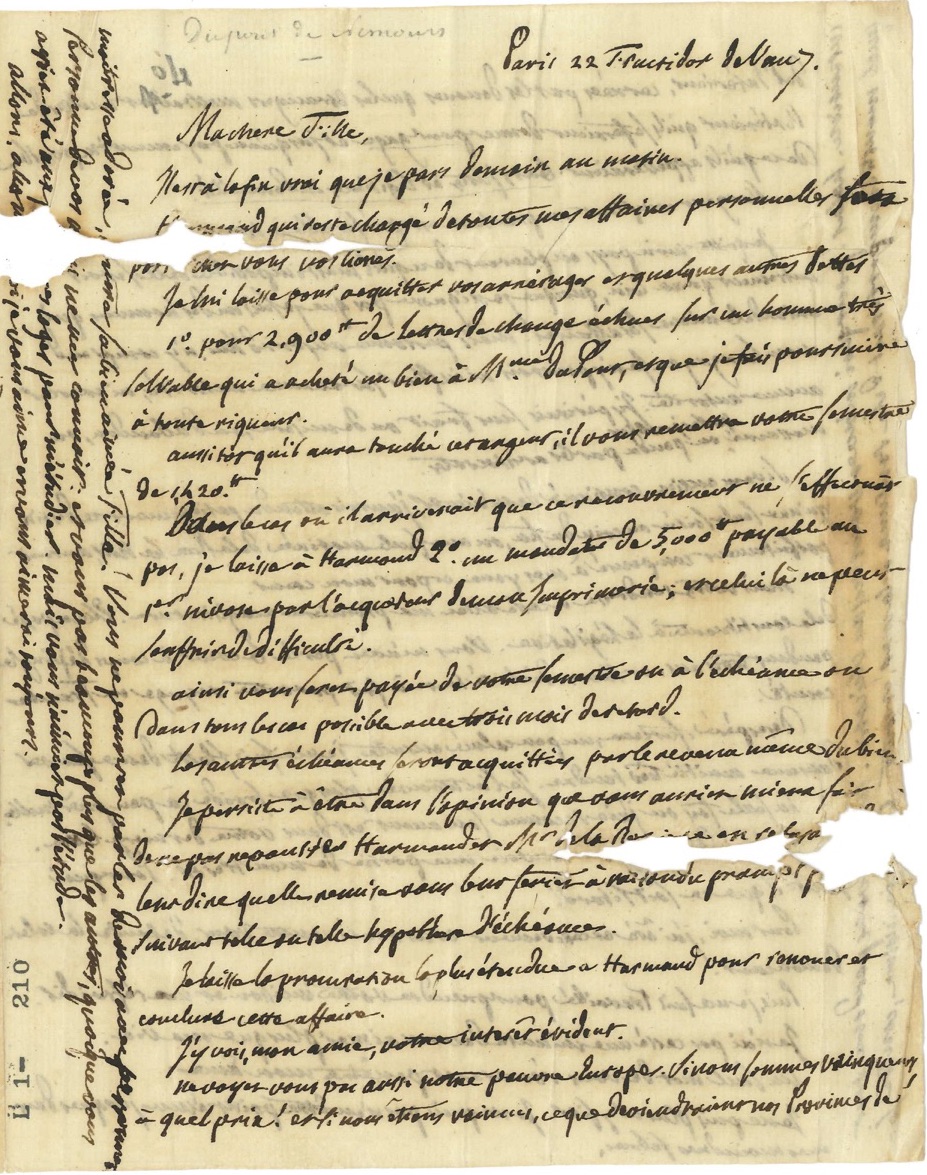

Thanks to an exploratory research grant, I spent a week at the Hagley Library in June of 2016 researching the correspondence of Pierre-Samuel du Pont de Nemours (1739-1817) and Marie-Anne Lavoisier (1758-1836). Hagley owns 143 manuscript letters between the two. While many of them are simple one-line dinner invitations, others are much longer, and reveal a deep and intimate relationship that lasted over 40 years.

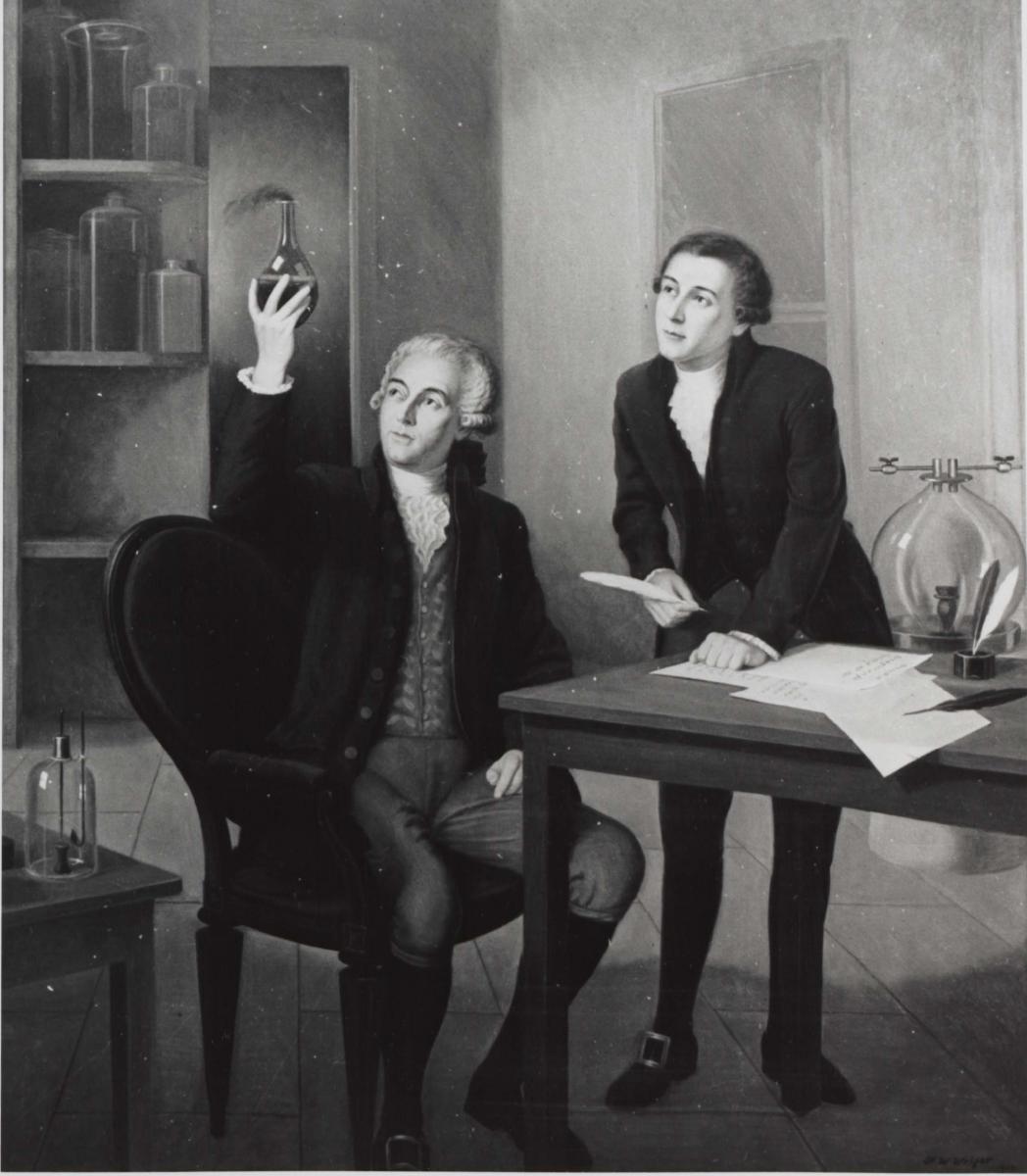

The du Pont and Lavoisier families were closely connected during a turbulent time in France. Pierre-Samuel was a dedicated public servant trying to navigate the storms of the French Revolution. Marie-Anne was the wife and scientific collaborator of Antoine Lavoisier, considered by many to be the founder of modern chemistry.

The two families held similar economic views, socialized, and even worked together. Pierre-Samuel sent his teenage son, Eleuthère Irénée, to apprentice with Monsieur Lavoisier. The techniques he learned laid the foundations to establish the Du Pont Company in 1802, after the family emigrated to America in 1799.

The letters also reveal that Mme Lavoisier and P.S. du Pont had an intimate relationship. In 1795, after Antoine Lavoisier’s untimely death by guillotine, P.S. proposed marriage to his friend’s widow. To his great dismay, he was rejected.

The families’ financial connections may have strained their relationship. Du Pont had borrowed 70,000 pounds from the Lavoisiers in 1791 to set up a print shop in Ile-de-France. The loan was backed up by a title to du Pont’s family property, Bois-des-Fossés, and the Lavoisiers were to receive bi-annual payments derived from the farm’s income. By 1798, payments were late and the value of the property itself had declined. In her letters, Mme Lavoisier pressed du Pont for the money.

I focused on five letters du Pont wrote to Mme Lavoisier between 1798 to 1801. In them, the line between their financial and emotional attachments begins to blur. In his letters, du Pont lays out a payment schedule, and demonstrates a desire to pay what is due. However, he also intimates that he is scraping for money everywhere, with no certainty of amassing the amount needed.

To make up the difference, du Pont attempts to substitute emotional and literary wealth for the financial sum. His debt negotiations and his professions of love coexist in the same letters and the two appear to blur.

In the end, du Pont quantifies his feelings for Mme Lavoisier by engaging in what I call “emotional accounting.” He conducts an inventory and draws an income statement of their relationship, where the concept of wealth is represented not in francs, but in the literary and cultural output dedicated to Mme Lavoisier, past, present, and future.

Aya Tanaka is an Adjunct Professor at the Management Communications Program at the Leonard N. Stern School of Business, New York University.