How do people think about what they do with and for money? I came to the Hagley Library twice to research this fascinating pecuniary question. I examined documents full of clues about outlooks on economic and financial matters. My aim was to better understand attitudes concerning money in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in both France and the United States.

As a Physiocrat, Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours (1739-1817) imagined alternatives to the political economy that was in place in France during his lifetime. But at the same time, he was often personally strapped for money and struggled for ways to get along. How, I wondered, did he see and describe his own money-making activities?

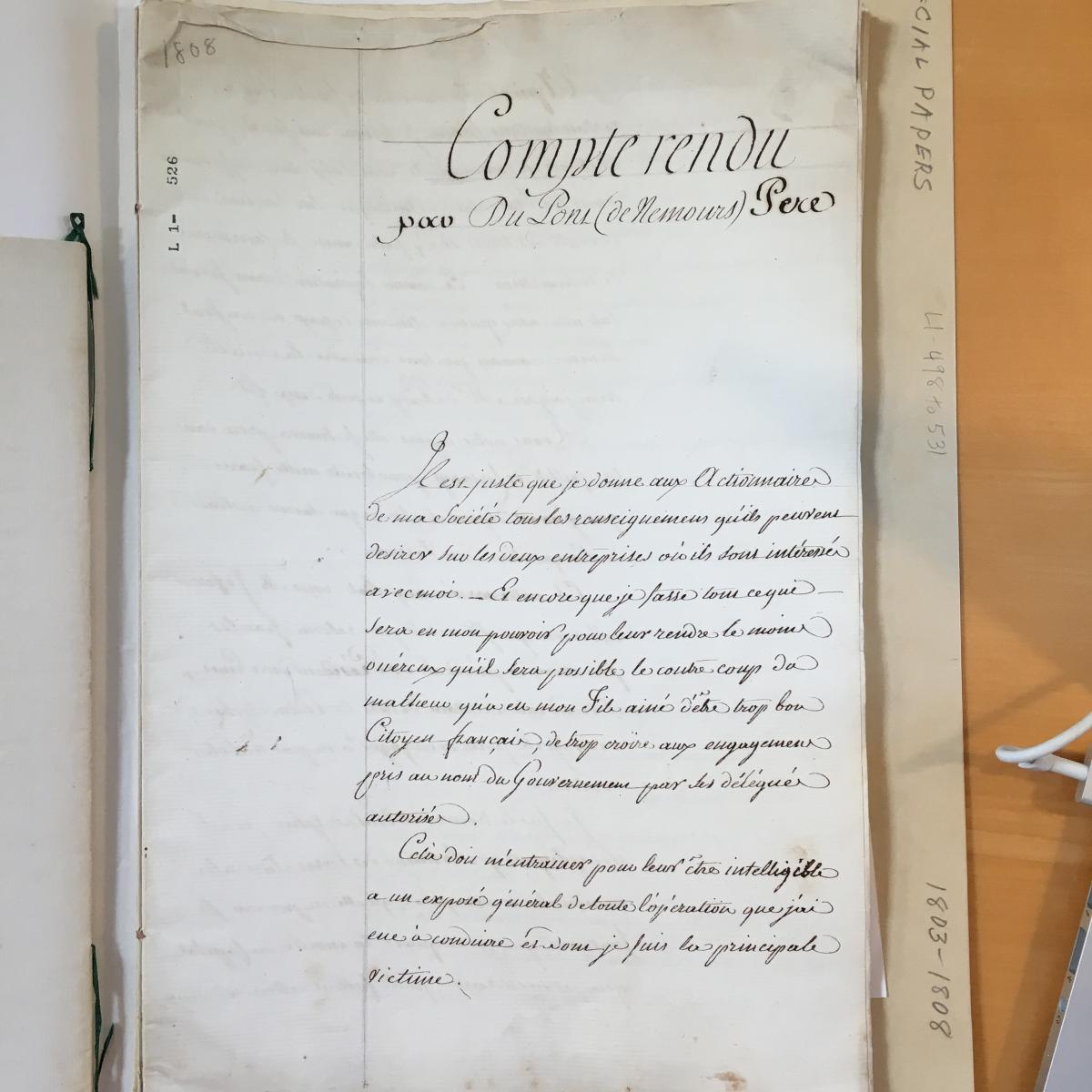

One shareholder report that du Pont authored in 1808 stood out to me while I was at the Hagley. As intimate as many a letter, it illuminates how personal relationships intersected with financial activity for the company founder and his associates.

“Compte rendu par Du Pont (de Nemours) aux Actionnaires de la Compagnie,”

dated 18 April 1808.Document L1-526, Longwood Mss. Group 1, Series B,

Special Papers of Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours.

Photo by Julia Abramson, with permission of the Hagley Museum and Library.

I thought about how unpleasant writing this shareholder report must have been for du Pont. Failures and losses constituted nearly the whole story of his business, originally conceived to carry out Atlantic maritime commerce. And yet, as Du Pont wrote: rien de cela n’était des affaires lucratives (none of this was lucrative business). The company soon dissolved.

In fact, du Pont’s company was practically doomed to fail due to bad management. A French émigré, he had neglected to research American customs where he sought to do business. And he was busy with other projects that he liked much more. In an 1803 letter that he wrote to his older son, du Pont described his routine: he devoted as little as one morning each week to company business.

Yet, as I filled in gaps with background research, I saw that the shareholder report presented intriguing, seemingly contradictory features. Despite the warning signs—which were practically screaming—early lists of shareholders and benefactors included several whose résumés in business and finance were stellar. As noted, du Pont had limited business acumen and little time to grow their investments. Why did these superstars place their money and their trust with du Pont?

Hagley ID 1969_2_1839, Box 13, Folder 10,

P.S. du Pont Longwood photograph collection (Accession 1969.002),

Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department.

I came to understood that personal ties and a shared culture, as much as profit, motivated investors in and benefactors to the unfortunate company. Investors had strong connections to du Pont, whether through family, friendship, other business, or all three. Dividends were less important than honoring reciprocal relationships in the group.

From the vantage point of 1808, the shareholder report reveals varied imperatives that influenced financial decisions in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Here, there was a mismatch between the expert knowledge of investors and the lesser quality of the investment. For this group, social loyalty, common culture, and effective motives competed with the goal of gaining a profit. The investment was in the man du Pont, as much as in the money that his company never made.

A professor of French and Francophone Studies at the University of Oklahoma, Julia Abramson has published two monographs, Learning from Lying: Paradoxes of the Literary Mystification (2005) and Food Culture in France (2007). She is now at work on a new book, Cultures of Finance from Versailles to the Elysée. She has recently published two articles: “Narrating ‘finances’ after John Law: Complicity, critique, and the bonds of obligation in Duclos and Mouhy” appears in the journal Finance and Society and “Pourquoi Piketty? French Enlightenment and the American Reception of Capital in the Twenty-First Century” appears in Common-place: The journal of early American life. She can be contacted by email at jabramson@ou.edu.