By the end of the 1960s, the Seagram Company had established itself as one of the largest distillers of alcoholic beverages in the world.

Its iconic new building at 375 Park Avenue in New York – the subject of a fascinating recent book by Phyllis Lambert – was both a masterpiece of corporate modernism and a symbol of the company’s influence within the American beverage industry. However, like other major beverage companies such as Budweiser, Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola, Seagram was eager to secure a foothold in new markets to ensure its expansion continued into the 1970s.

The impact of the civil rights movement, alongside the influence of pioneering black public relations professionals such as D. Parke Gibson, had radically shifted corporate attitudes towards the black consumer during the 1950s and 1960s. Thanks to a generous grant from the Hagley Library, I was able to explore the Seagram collections for a week in spring 2016 to examine one of company’s earliest efforts to court the black consumer market – an annual ‘Black Historical Calendar.’

First introduced in 1969 as the “Negro Historical Calendar,” the Seagram calendar aimed to celebrate famous black Americans and their “significant contributions to the history of the United States.” As press releases I found in Seagram’s collections demonstrate, the calendar project became a key part of the company’s strategic efforts to court black consumers, based around a celebration of black heritage and an emphasis on educational value.

Seagram advertised the calendar in popular black periodicals such as Ebony magazine, informing readers that by sending a check, cash or money order for $1.00, they could receive “a dramatic record of Negro achievement.” Steven Lockett, Seagram’s assistant to the vice president-general sales manager, announced that by 1971 the company was distributing more than 100,000 calendars annually, and stressed its value “as a teaching aid, as an almanac and as a record of achievement.” By explicitly situating the calendar as an educational tool which offered “the perfect source material for Black Studies classes,” Seagram were able to connect themselves to the development of the Black Studies Movement which spread across American college campuses during the early 1970s.

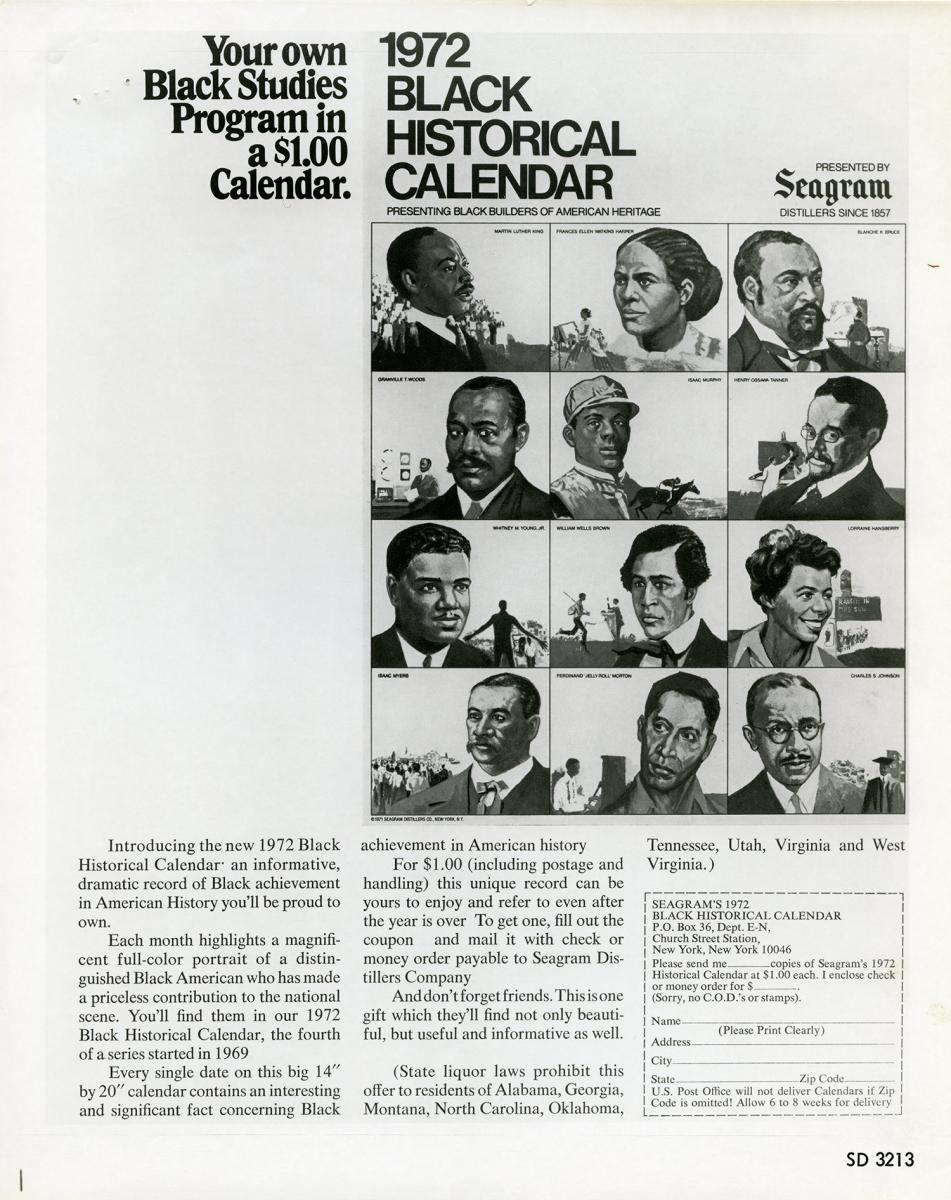

Seagram Black Historical Calendar, 1972. Seagram Museum collection of photographs and audiovisual material at Hagley.

As one of the most comprehensive early attempts to utilise black history as a marketing strategy, Seagram used the Black Historical Calendar to position itself as a gatekeeper for what Vincent Harding has described as the “modern black history revival.” However, the composition of these calendars also highlighted some of the challenges created by corporate interventions into popular black history and education. Firstly, Seagram’s emphasis on “contributionism” through the role of exceptional black individuals served to downplay political radicalism in favour of artistic or technological ingenuity. Secondly, Seagram offered a heavily gendered vision of the black past. As this image from the 1972 Black Historical Calendar shows, less than twenty percent of the “black builders of American heritage” represented in the calendar were women – a disparity which was broadly consistent across the majority of Seagram’s black history content.