The basic ingredients found in nearly every type of beer are water, malted barley, hops, and yeast. Hot water is mixed with crushed barley malt grains to produce a sugary liquid called wort. The wort is then drained off the spent grains and boiled with hops to add flavor. After the hopped wort is chilled, yeast is introduced to the liquid, inducing fermentation as the yeast converts the sugars in the wort to alcohol. Most beers are left to ferment from one to three weeks, then allowed to age for a week or longer before packaging.

Advertisement

Joh. Barth & Sohn, hop growers and dealers

From American Brewer, publication of the Master Brewers' Association of America 1940

Hagley Museum & Library

Imprints Department

Call number HD9397.A1 A5

Advertisement

Mellomalt

U.S. Malt Company

From American Brewer, publication of the Master Brewers' Association of America

1939

Hagley Museum & Library

Imprints Department

Call number HD9397.A1 A5

Advertisement

Hans Hinricks, Inc., malt & hops dealer

From American Brewer, publication of the Master Brewers' Association of America

1940

Hagley Museum & Library

Imprints Department

Call number HD9397.A1 A5

Advertisement

Advertisement

Hans Hinricks, Inc., malt & hops dealer

From American Brewer, publication of the Master Brewers' Association of America

1940

Hagley Museum & Library

Imprints Department

Call number HD9397.A1 A5

Pamphlet

Pamphlet

On hops

M.H. Russ & Company, hop merchants

Prague

1876

Informational pamphlet about hops printed for the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hagley Museum & Library

Imprints Department

Accession Pam 2004.676

Hops

Hops

Hops flowers and grains of malted barley ready to be used for brewing beer.

Hagley Museum & Library

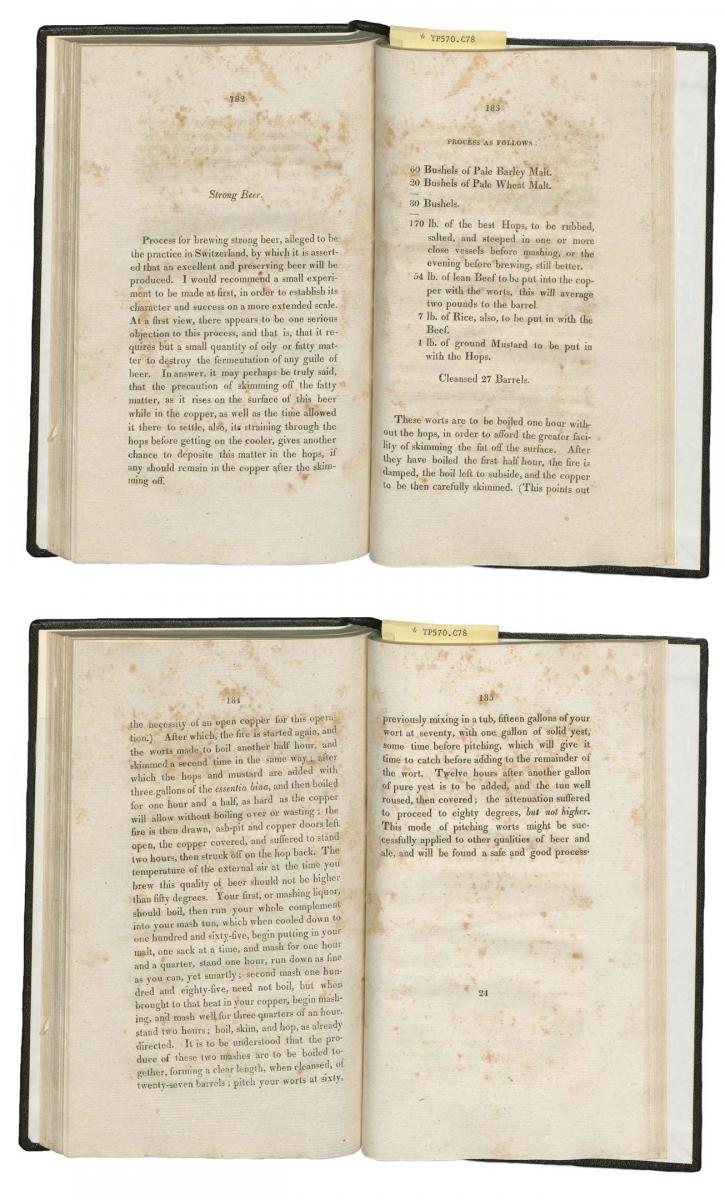

Recipe for Strong Beer

The American practical brewer and tanner

by Joseph Coppinger

1815

Early beer recipes often called for unusual ingredients; this recipe from 1815 lists lean beef and ground mustard in addition to barley and hops.

Text of recipe:

Process for brewing strong beer, alleged to be the practice in Switzerland, by which it is asserted that an excellent and preserving beer will be produced. I would recommend a small experiment to be made at first, in order to establish its character and success on a more extended scale. At a first view, there appears to be one serious objection to this process, and that is, that it requires but a small quantity of oily or fatty matter to destroy the fermentation of any guile of beer. In answer, it may perhaps be truly said, that the precaution of skimming off the fatty matter, as it rises on the surface of this beer while in the copper, as well as the time allowed it there to settle, also, its straining through the hops before getting on the cooler, gives another chance to deposite this matter in the hops, if any should remain in the copper after the skimming off.

PROCESS AS FOLLOWS:

60 Bushels of Pale Barley Malt.

20 Bushels of Pale Wheat Malt.

—

80 Bushels

—

170 lb. of the best Hops, to be rubbed, salted, and steeped in one or more close vessels before mashing, or the evening before brewing, still better.

54 lb. of lean Beef to be put into the copper with the worts, this will average two pounds to the barrel.

7 lb. of rice, also, to be put in with the Beef.

1 lb. of ground Mustard to be put in with the Hops.Cleansed 27 Barrels.

These worts are to be boiled one hour without the hops, in order to afforc the greater facility of skimming the fat off the surface. After they have boiled the first half hour, the fire is damped, the boil left to subside, and the copper to be then carefully skimmed. (This points out the necessity of an open copper for this operation.) After which, the fire is started again, and the worts made to boil another half hour, and skimmed a secont time in the same way ; after which the hops and mustard are added with three gallons of the essential bina, and then boiled for one hour and a half, as hard as the coller will allow without boiling over or wasting ; the fire is then drawn, ash-pit and copper doors left open, the copper covered, and suffered to stand two hours, then struck off on the hob back. The temperature of the external air at the time you brew this quality of beer should not be higher than fifty degrees. Your first, or mashing liquor, should boil, then run your whole complement into your mash tun, which when cooled down to one hundered and sixty0five, begin putting in your malt, one sack at a time, and mash for one hour and a quarter, stand one hour, run down as fine as you can , yet smartly ; second mash one hundred and eighty-five, need not boil, but when brought to that heat in your copper, begin mashing, and mash well for three quarters of an hour, stand two hours ; boil, skim, and hop, as already directed. It is to be understood that the produce of these two mashes are to be boiled together, forming a clear length, when cleansed, of twenty-seven barrels ; pitch your worts at sixty, previously mixing in a tub, fifteen gallons of your wort at seventy, with one gallon of solid yest, some time before pitching, which will give it time to catch before adding to the remainder of the wort. Twelve hours after another gallon of pure yest is to be added, and the tun well roused, then covered ; the attenuation suffered to proceed to eighty degrees, but not higher. This mode of pitching worts might be successfully applied to other qualities of beer and ale, and will be found a safe and good process.

Hagley Museum & Library

Imprints Department

Rare Books

Call number RARE TP570 .C78