Patent medicine promoters pioneered many advertising and sales techniques. Patent medicine advertising often touted exotic ingredients, even if their actual effects came from more practical elements. The producers of many of these medicines used a primitive version of branding to distinguish themselves from their many competitors.

Within the English-speaking world, patent medicines are as old as journalism. The marketing of patent medicine formulas fueled the circulation of early newspapers. Newspaper and magazine advertising helped spread the word of these nostrums to the country's most remote corners.

By the 19th century, American newspapers were awash in patent medicine advertising. Their advertising and labels were very enticing: "Eckman's Alterative for all throat and lung diseases;" "Cerralgine Food for the Brain, a safe cure for headache, neuralgia, nervousness, insomnia, etc.;" and "Drs. Mixer, sole manufacturers and proprietors of Mixer's Cancer and Scrofula syrup; the world renowned blood purifier."

A number of American institutions owe their existence to the patent medicine industry, most notably a number of the older almanacs, which were originally given away as promotional items by patent medicine manufacturers and distributed at druggists' counters. In the 1840s almanacs published by the manufacturers of patent medicines began to appear, such as Jayne’s Medical Almanac and guide to health from the Philadelphia drug giant David Jayne. Some of these almanacs had lengthy runs well into the 20th century.

Advertising for patent medicines was not limited to newspapers and almanacs. Printed broadsides were major sources of commercial information. Early broadsides dealt with epidemics, providing suggestions to prevent the spread of diseases.

In the early 18th century broadside advertisements by druggists and apothecaries began to surface, usually in the form of product lists offered for sale. Later, broadsides with lengthier texts, describing the value of proprietary medicines and frequently joined by testimonials, accompanied these lists.

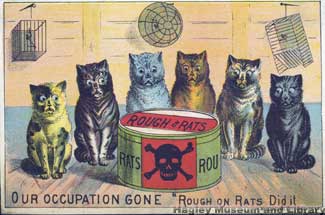

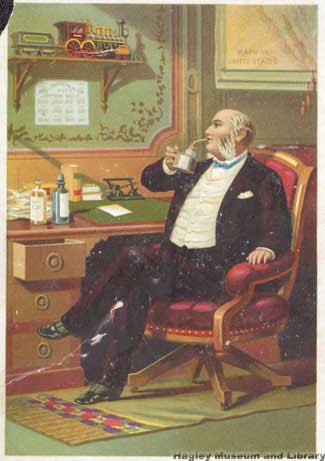

Trade cards were very popular in the Victorian era. They typically featured a very colorful, eye-catching picture with advertising slogans on the front side, and full advertising text (and sometimes testimonials) on the back. Varying from funny to risqué, trade cards immediately became popular collectors’ items. Almost every type of product or service imaginable was advertised in this way, including patent medicines.

An astonishing number of patent medicine trade cards have survived today, due to the fact that they were collected extensively and saved in scrapbooks.

Manufacturers’ trade catalogs and pamphlets were also used for patent medicine advertising. Since pamphlets, like newspapers, were usually discarded after reading, these items are not as common today as trade cards and broadsides.

Familiar brands from the patent medicine era

A number of brands of consumer products that date from the patent medicine era are still on the market today, although their ingredients have changed and the claims made for the benefits they offer seriously revised. Here are a few:

- Bromo-Seltzer

- Carter’s Little Liver Pills

- Doan’s Pills

- Geritol

- Goody’s Headache Powder

- Luden Brothers Cough Drops

- Phillips’ Milk of Magnesia

- Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound

Some consumer products were once marketed as patent medicines, but are now used for non-medicinal purposes. Their original ingredients may have been changed to remove drugs, as with Coca-Cola, or the product may be used now for a different purpose. Some examples include:

- Angostura Bitters

- Bovril

- Coca-Cola

- Dr. Pepper

- Hires Root Beer

- Moxie brand soda

- Tonic water